Croatian Glagolitic Script

© by Darko Zubrinic, Zagreb (1995)In the history of Croatian people three scripts were in use:

- Croatian Glagolitic Script,

- Croatian Cyrillic Script (bosancica),

- Latin Script.

Today the Croats are using exclusively the Latin Script.

The Arabica was also in use among the Muslims in Bosnia-Herzegovina. It was in fact the Arabic script used for the Croatian language and it constitutes the so-called Adjami or Aljamiado literature, similarly as in SpainF. Its first sources in Croatia go back to the 15th century. One of the oldest texts is a love song called Chirvat-türkisi (Croatian song) from 1588, written by a certain Mehmed. This manuscript is kept in the National Library in Vienna. Except for literature Arabica was also used in religious schools and administration. Of course, it was in much lesser use than other scripts. The last book in Arabica was printed in 1941.

It is important to emphasize that the earliest known texts of Croatian literature written in the Latin script (14th century) have traces of Church-slavonic influences. Hence, Croatian glagolitic, Cyrillic and Latin traditions cannot be viewed as separated entities. We know that Middle Age Croatian scriptoriums were polygraphic (for example in Zadar and Krk), see [Malic, Na izvorima..., pp 35-56].

Jewels of the Croatian glagolitic culture:

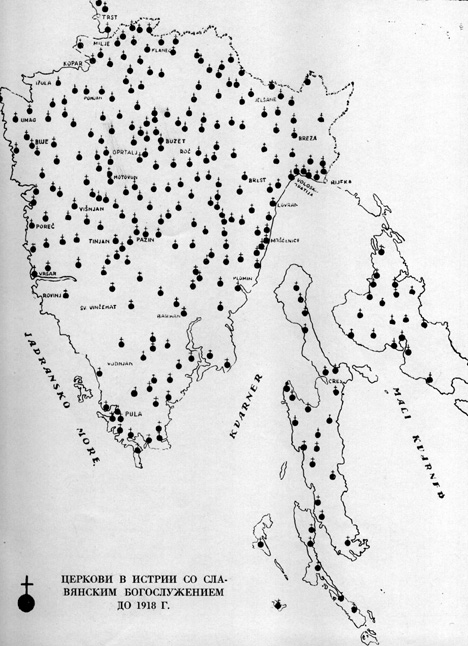

he

Croatian Glagolitic

alphabet has a long and interesting history of more than a thousand

years. The Croats using the Glagolitic alphabet were the only nation in

Europe who was given a special

permission by Pope Innocent IV

(in 1248) to use their own language and this script in liturgy. More

precisely, this permission had formally been given to the bishop

Philip of Senj.

However, special

care accorded by the Vatican to

the Glagolitic liturgy in subsequent centuries (even by publishing

several Glagolitic missals in Rome), shows that this privilege applied

to all Croatian lands using the Glagolitic liturgy, mostly along the

coast. As is well known, the Latin had been the privileged language in

religious ceremonies in the Catholic Church until the 2nd Vatican Synod

kept in 1962-1965, when it was decided to allow vernacular national

languages to be used in the Catholic liturgy instead of Latin. It is

interesting that even today the Glagolitic liturgy is used in some

Croatian churches.

he

Croatian Glagolitic

alphabet has a long and interesting history of more than a thousand

years. The Croats using the Glagolitic alphabet were the only nation in

Europe who was given a special

permission by Pope Innocent IV

(in 1248) to use their own language and this script in liturgy. More

precisely, this permission had formally been given to the bishop

Philip of Senj.

However, special

care accorded by the Vatican to

the Glagolitic liturgy in subsequent centuries (even by publishing

several Glagolitic missals in Rome), shows that this privilege applied

to all Croatian lands using the Glagolitic liturgy, mostly along the

coast. As is well known, the Latin had been the privileged language in

religious ceremonies in the Catholic Church until the 2nd Vatican Synod

kept in 1962-1965, when it was decided to allow vernacular national

languages to be used in the Catholic liturgy instead of Latin. It is

interesting that even today the Glagolitic liturgy is used in some

Croatian churches.

In 1252 the Pope Innocent IV allowed Benedictine Glagolitic monks in Omisalj on the largest Croatian island of Krk to use the Croatian Church-Slavonic liturgy and the Glagolitic Script instead of Latin.

The Rules of St. Benedict, written in Croatian Glagolitic Script in 14th century, are among the earliest known translation of Benedictine rules from Latin into a living language (Croatian Church-Slavonic). Altogether 60 pages are preserved out of 70, that Benedictines had to know by heart. For more information see Regula sv. Benedikta.

We also know that Croatian Glagolitic Benedictines existed in the city of Krk, and on the island of Pasman near Zadar. Even more peculiar was the existence of Benedictines on the island of Brac near Split, in Povlja, who used the Croatian Church-Slavonic liturgy, and - the Croatian Cyrillic Script! It should be noted that members of the Benedictine monastic order were strict followers of the Latin liturgy and of the Latin language and script everywhere in Europe - except in parts of the Croatian littoral.

According to rev. Ivan Ostojic, outstanding specialist on the history of benedictines in Croatia, in 13th and 14th centuries Croatia had as many as 70 known benedictine monasteries for monks, and more than 20 for nuns. This represented tremendous intellectual force in Croatia. Recall the benedictine motto - Ora et labora. See [Gregory Peroche], p. 40.

Have a look at some exotic Croatian Glagolitic letters and the list of Glagolitic breviaries and missals!

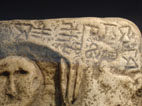

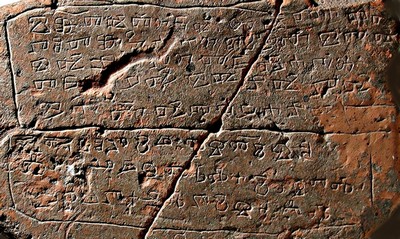

ery

important monument, containing an

inscription written in the Croatian Glagolitic alphabet is a stone

tablet - Bascanska

ploca (Baska Stone

Tablet), dating from the end of 11th century, found in the church of

St. Lucy near the town of Baska on the island of Krk.

It contains about 400 Glagolitic characters (dimensions of the tablet:

2x1 sq.m, 800 kg). Its particular importance lies in the following

three words carved in stone:

ery

important monument, containing an

inscription written in the Croatian Glagolitic alphabet is a stone

tablet - Bascanska

ploca (Baska Stone

Tablet), dating from the end of 11th century, found in the church of

St. Lucy near the town of Baska on the island of Krk.

It contains about 400 Glagolitic characters (dimensions of the tablet:

2x1 sq.m, 800 kg). Its particular importance lies in the following

three words carved in stone:

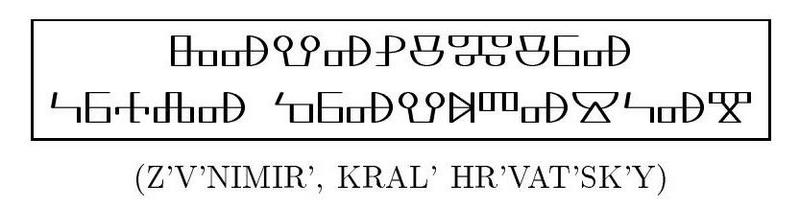

Zvonimir, Croatian King (note that there are no spacings between words)

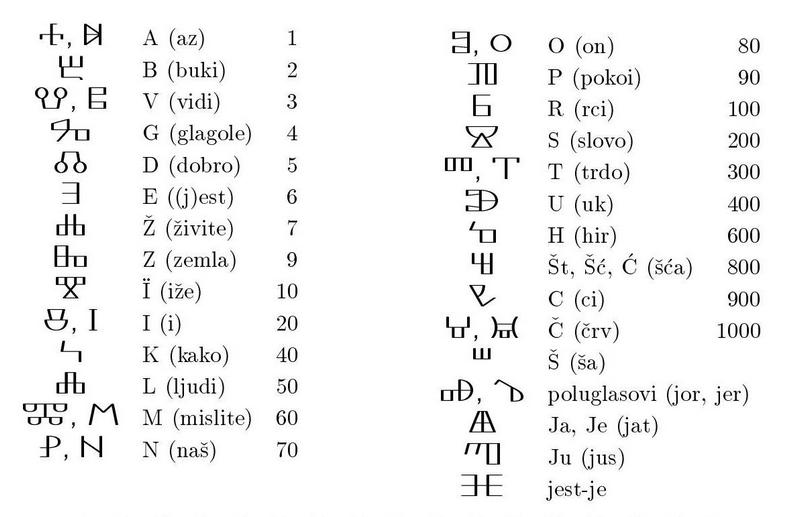

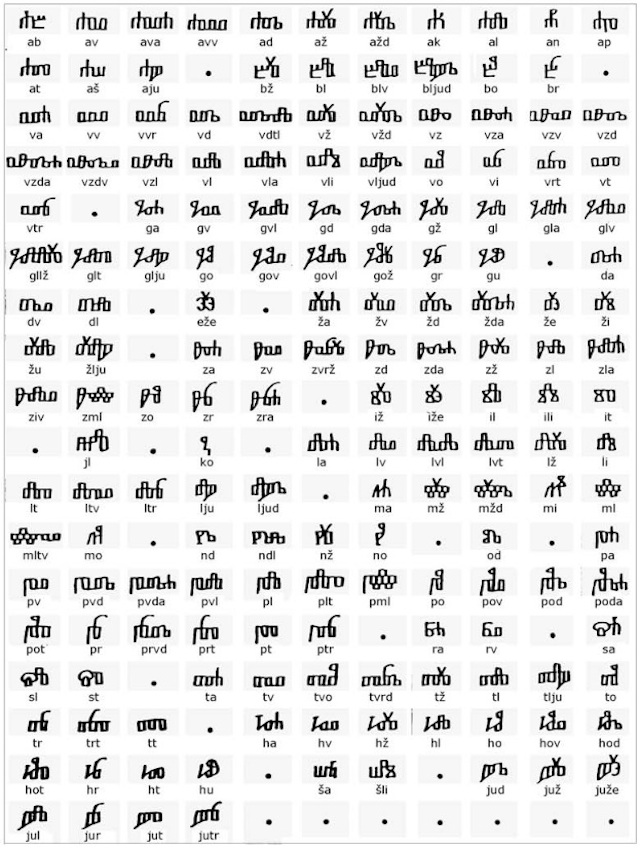

Table of Croatian Glagolitic Script on the Baška Tablet. The Latex font created by D.Ž., using METAFONT.

You can see them in the third line - Z'v'nimir', kral' hr'vat'sk'y, in the most solemn position on the tablet, perfectly centered. Very few nations in Europe can boast of having such an extensive written monument in their vernacular language (with some elements of Church Slavonic) as early as the 11th century.

Look at the

- The Baska Tablet web page

- reconstructed content of the Baska table - with spacings between words. The photo on the right is a reconstruction of the Baska Tablet made by academician Branko Fucic. On the left you can see how it looks now, click on it (98 Kb).

- Wen: Baska tablet, Appleby, Drenova.

- episode with the British Prince Philip, related to the Baska tablet.

We must point out the following important fact: Glagolitic inscriptions

carved in stone (hundreds of them, the earliest known dating from the

11th century) exist only on Croatian soil, and nowhere else.

There are clear indications that the origin of the famous historical source Sclavorum Regnum, known as Ljetopis popa Dukljanina and Croatian Chronicle, was written in the Glagolitic script. This very old text represents the earliest known historiographical work about Croats and the earliest known literary text in Croatian language.

![]()

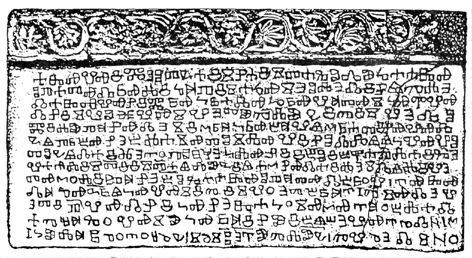

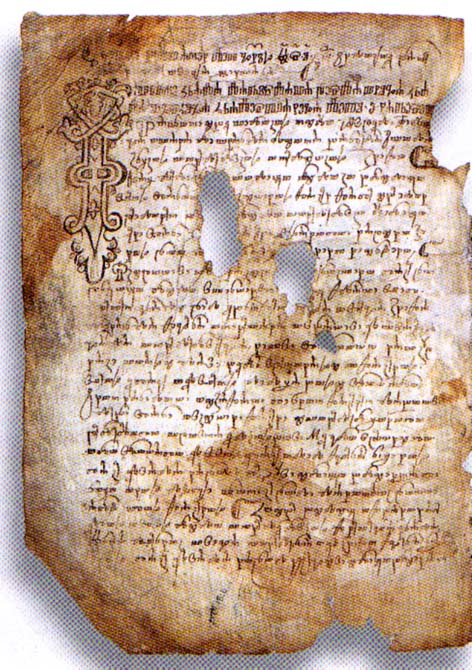

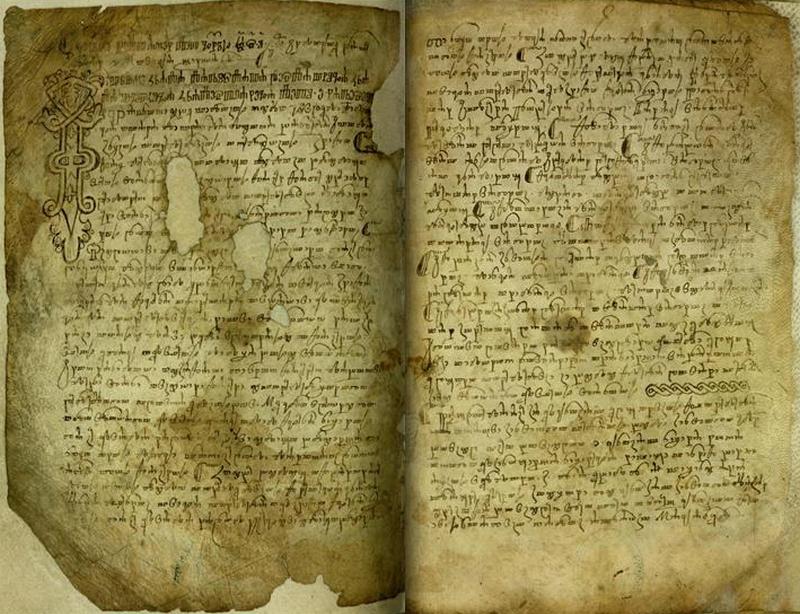

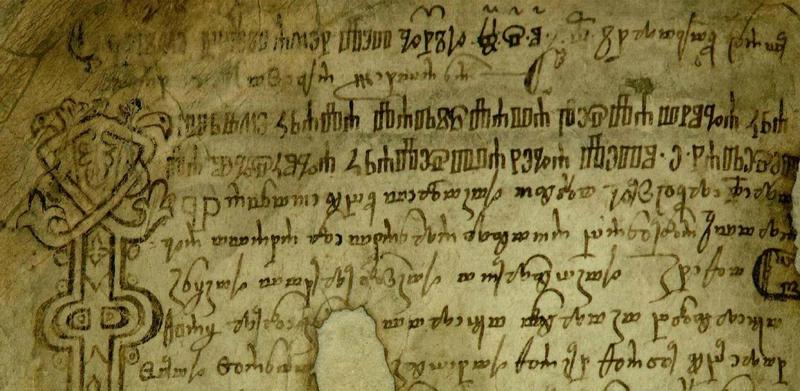

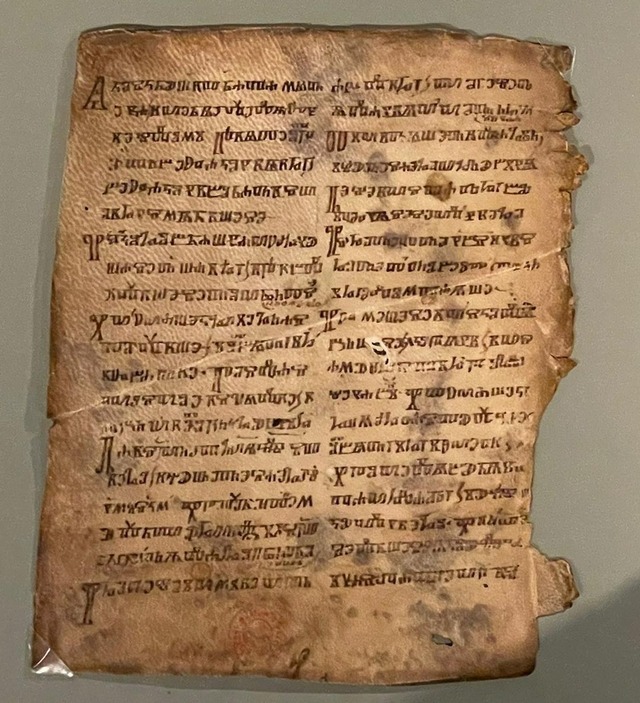

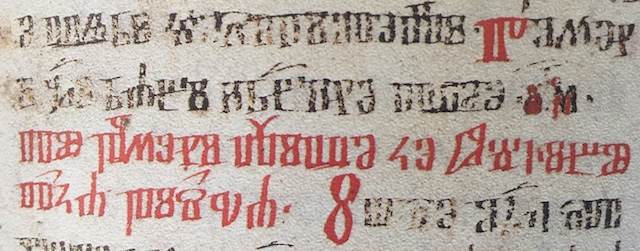

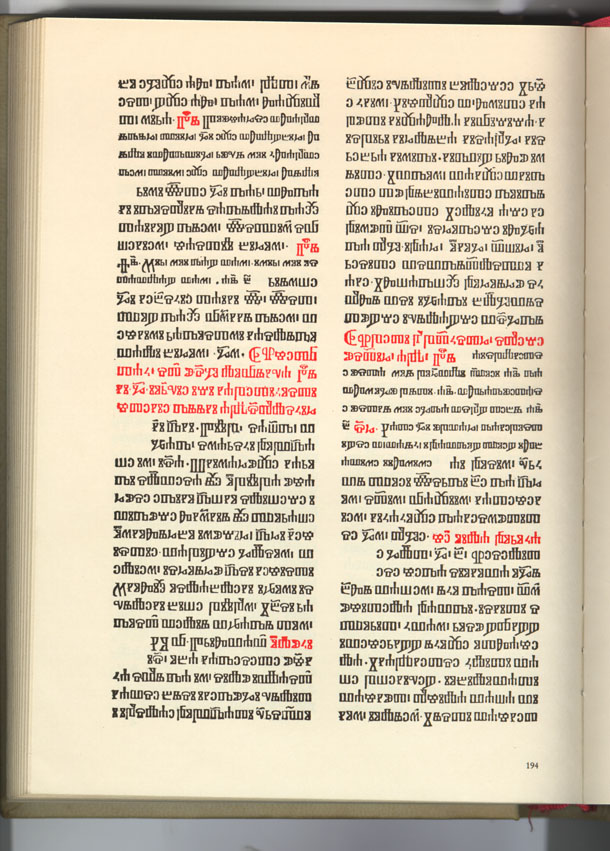

ne

of the earliest and most important

Croatian legal documents is The

Vinodol Code, very different

from the Roman law, written in the

Glagolitic alphabet in 1288. It also introduced the institution of

witnesses. It was unique in Europe by determining moral protection and

integrity of women. The Vinodol Code does not allow torture during

legal proceedings, and is considered to be one of the most important

documents of medieval Europe. Among the Slav Codes only the Rus'

Code "Pravda" is slightly older

(1282). The first Croatian edition

of the Vinodol Code was published in Zagreb in 1843. Two of its Russian

translations with comments were issued soon after: in Moscow in 1846

and in St. Petersburg in 1878. A translation of the Vinodol Code into

Polish appeared in 1856 and into French in 1896 (Jules Preux: La Loi du

Vinodol traduite et annotée // Nouv. rev. hist. du droit

français et étranger. - 1896).

ne

of the earliest and most important

Croatian legal documents is The

Vinodol Code, very different

from the Roman law, written in the

Glagolitic alphabet in 1288. It also introduced the institution of

witnesses. It was unique in Europe by determining moral protection and

integrity of women. The Vinodol Code does not allow torture during

legal proceedings, and is considered to be one of the most important

documents of medieval Europe. Among the Slav Codes only the Rus'

Code "Pravda" is slightly older

(1282). The first Croatian edition

of the Vinodol Code was published in Zagreb in 1843. Two of its Russian

translations with comments were issued soon after: in Moscow in 1846

and in St. Petersburg in 1878. A translation of the Vinodol Code into

Polish appeared in 1856 and into French in 1896 (Jules Preux: La Loi du

Vinodol traduite et annotée // Nouv. rev. hist. du droit

français et étranger. - 1896).

The code was published in many European countries: it was translated into at least nine languages. Some of them are Russian (1846, 1878), Polish (1856), French (1896), German (1931, 1987), Italian (1987). For more information see here, and at the Croatian National and University Library in Zagreb.

The Vinodol Code (1288)

expressly mentions the notion of "Croatian

language" (hervatski), in

Article 72.

Vinodolski zakon 1288, scrollable book, National and University Library, Zagreb

The Statute of Vinodol from 1288, British Croatian Review No. 14, May 1978, in English, with commentaries (Ante Cuvalo web site)

There are many other important legal documents regarding medieval Croatia, of which mention should be made

- the Korcula

codex (from the island of

Korcula,

1214, statute of the city and island written in Latin),

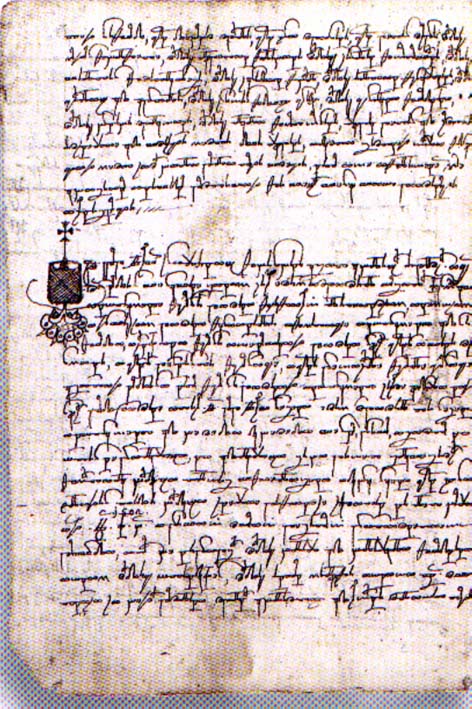

- Istarski

razvod

(Istrian

Book of Boundaries) from the Istrian

peninsula,

1275, written originally in

three languages: Croatian in the

Glagolitic alphabet, Latin

and German (over the longer period

until 1395).

It defined the border between different rulers in Istria.

Only

the Croatian Glagolitic version has been preserved.

Istarski razvod has 67 pp, and mentions the Croatian name expressly 25 times. Moreover, the Istarski razvod expressly mentions the the notion of "Croatian language" (jazik hrvatski) in each of these 25 instances. There are Latin and Italian translations from Croatian dating from the 16th century, which kept the original Croatian names for many places, proof that the population in the Istrian hinterland was dominantly Croatian. By its juridical and literary value it can be ranked among the most interesting documents of that time in Europe. It is also the oldest international diplomatic document written in Croatian. Earlier written documents bear witness to the presence of the Croats in Istria from the seventh century. See a scrollable book Istrian Book of Boundaries provided by the National and University Library in Zagreb.

Istarski razvod, [PDF] 5.5 MB

transliteration from Croatian Glagolitic into Latin Script;

source [Luka Kirac] - the Statute of the Poljica Principality

(1444, near Split),

written in the Croatian

Cyrillic Script. The

Poljica Principality (Poljicka knezija) was a unique phenomenon in

Europe. It existed continuously for almost seven centuries, with its

own very original legal system. Russian scientist P. Alexeev believes

that Thomas More wrote his ``Utopia (The Perfect State)'' (Louvain,

1516) inspired by the Poljica Principality. Thomas More calls Poljica

man - Poly(it)eritu, i.e. those who use more scripts (3 scripts:

Glagolitic, Cyrillic, and Latin). Legend has it that the Principality

was founded by three sons of dethroned Croatian king Miroslav in the

mid 10th century. It was abolished during the French rule in 1807. As

remarked by scientists already in the 19th century, the "Poljica

Statute" is very closely related to the above mentioned Rus'ka Pravda,

though they appeared in very distant areas (Kyjiv Rus' and Dalmatia).

See [Pascenko],

p. 272.

One of the items of Poljica statute is that "everybody has the right to live," contrary to many medieval European laws replete with punishments involving torture. Thomas More added to the 1516 edition of his Utopia a frontispiece showing 4 lines in the Utopian language and Utopian alphabet. According to Alexeev, those who know Glagolitic script, at a first glance cannot resist the idea that ``some letters in these four lines are in fact written in the Glagolitic script'' (see [Mardesic], p. 147). It is rather amazing that there are as many as four to five thousand private legal documents (contracts, testaments, etc.) kept within Poljica families, and wirtten in the Croatian Cyrillic.

Edo Pivcevic: The Poljica Statute

Source: Dr. Petar Karlić: Statut lige kotara ninskoga 1103 [PDF], Mjesečnik pravničkog društva u Zagrebu, 1913.

Vrbnik Statute from 1388

We know of several Croatian city statutes written in the Glagolitic Script:

- the Vrbnik Statute (on the island of Krk), written in 1388,

- the Kastav Statute (1490, Istria, near Rijeka), preserved in Latin, translated from the Glagolitic Script,

- Moscenica Statute (~1501, Istria), preserved in Latin, translated from the Glagolitic Script,

- the Veprinac Statute (1507, Istria), preserved in the Glagolitic.

In the Krk Diocese there were several parishes with glagolitic village chapters: Baska, Dobrinj, Omisalj, and Vrbnik (on the island of Krk), and Beli, Lubenice, Valun (on the island of Cres).

Except for the very rich sacral literature, there are thousands of other documents proving that the Glagolitic alphabet was also used in the administration and in private communication.

The oldest known

Croatian nonliturgical verses (10 poems) are

from 1380, written in cakavian dialect in the Glagolitic collection Code

Slave 11, which is now kept in

Bibliothéque Nationale,

Paris. (Many thanks to Mrs. Biserka Krslin-Barda, Paris, for the link.)

Glagolitic inscription containing the year 1330 (in the third line), when the church of St. Martin in Senj was built.

On the photo Mrs. Mirna Lipovac.

The oldest Croatian church containing a glagolitic inscription denoting the year when it was built (the year also being carved in glagolitic letters) is the church of St. Martin in the city of Senj. The indicated year is 1330; see the above photo. It is the oldest such church not only in Croatia, but in general. Information by the courtesy of Darijo Tikulin, Zadar.

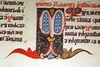

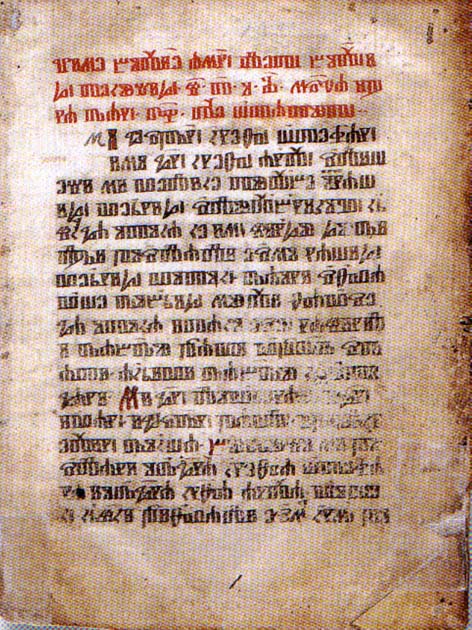

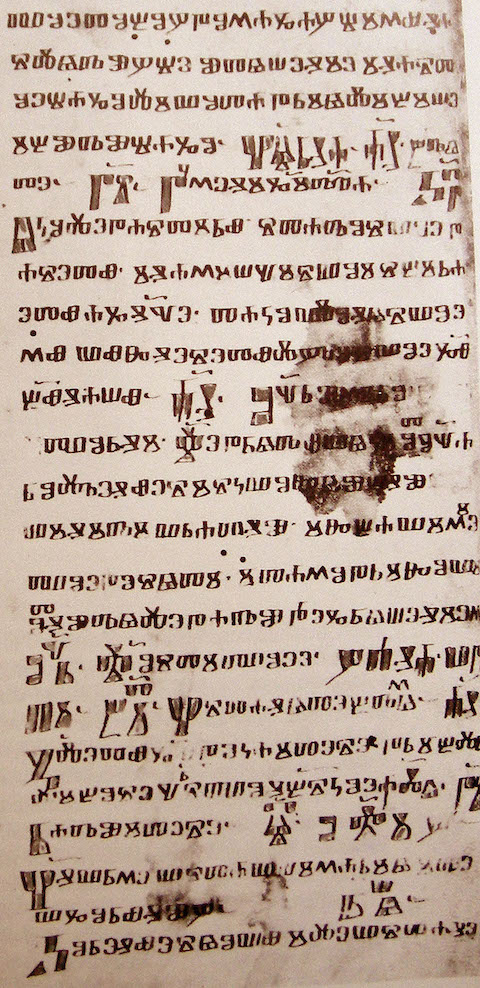

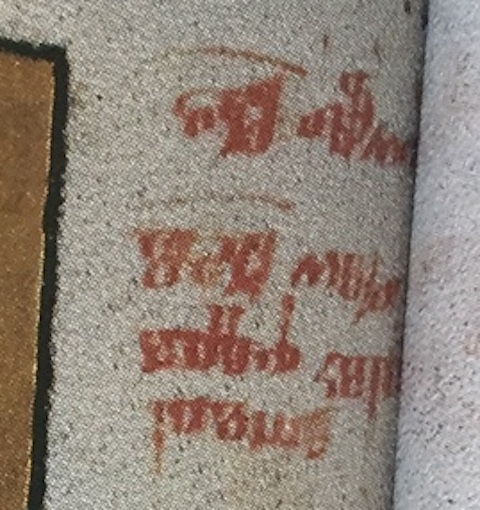

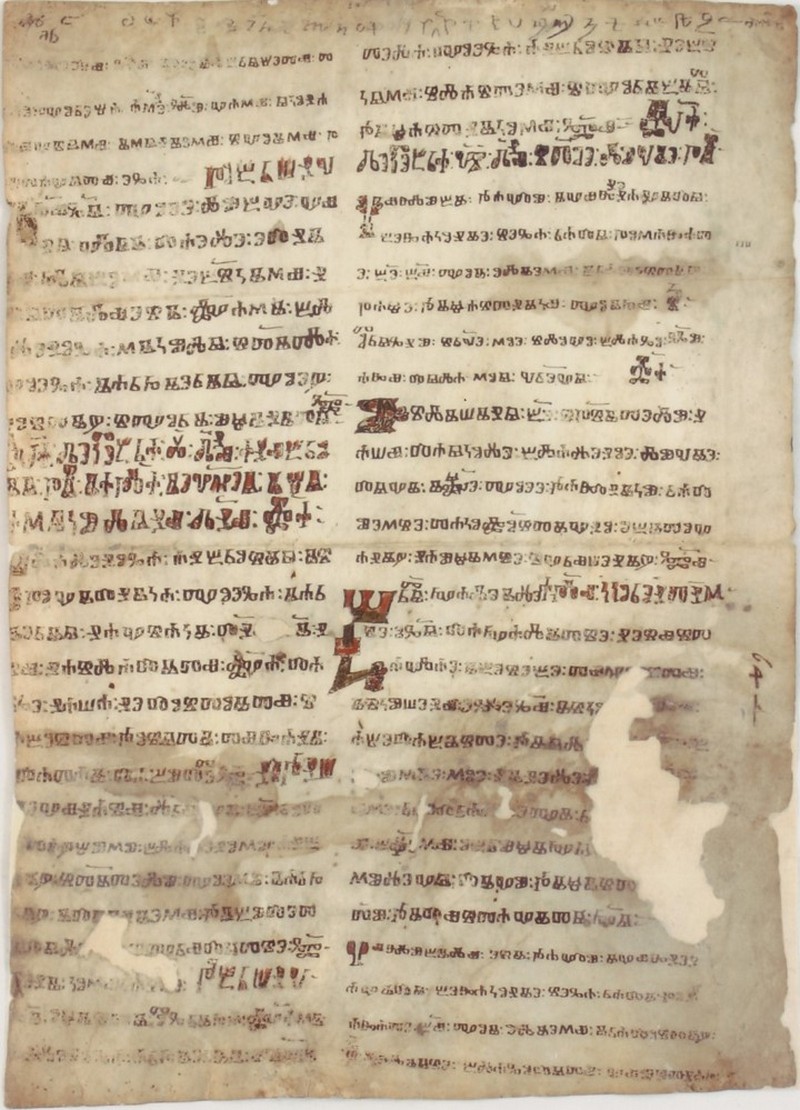

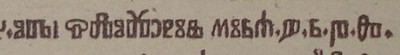

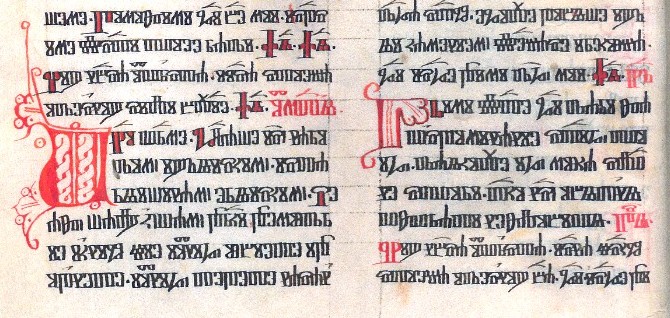

We provide a photo of fragment of a Croation Glagolitic Breviary, written circa A.D. 1225. It is kept in London, in the British Museum Add. 31951, folio 1. (from A History of Writing, Albertine Gaur).

One may note the angular forms of the glyphs (typical Croatian) and the coloring of numerous letters, similar to various Latin codices. Croatia was/is normally under Latin sway. The above photo represents the right-hand column of the front page. The whole page can be seen here: [JPG]. Source of the photo and of the description is www.biblical-data.org.

The

famous Czech

king Charles IV of Luxemburg built a Glagolitic

convent Emaus (na

Slovaneh) in Prague in 1347,

where eighty Croatian Benedictines

from the island of Pasman (near the city of Zadar) or Senj were

invited. It is remarkable that

the convent is not far from the famous Charles University, built the

next year, in 1348 (Charles IV also founded the University of Vienna in

1365). One of the Glagolitic books from this convent (Emaus) in Prague

came to Reims in 1574, where according to a legend for centuries

the French kings (Charles

IX, Henri II, Louis XIII, Louis XIV) were sworn in by putting their

hands on this holy book, known under the name Texte

du Sacre or L'Évangile

de Reims.

This Glagolitic book

was written in 1395, and represents a copy of an older Croatian book,

written probably in Omisalj. In fact, the Glagolitic book was bound

together with a Cyrillic book dating from the 11th century

(the

Cyrillic part has 16 leaves, and the Glagolitic part has 31 leaves).

The book was ornamented with gold, precious stones and relics, and

according to [Dolbeau],

p 26-27, probably

calligraphed on the island of Krk or in a Czech monastery. These

Dolbeau's pages are available at [Studia Croatica].

The

French kings were, according to the said legend, sworn in with the

Glagolitic book using the following words:

(So we swear, vow and promise on the Holy and True Cross and on the Gospel that we touch.)

Precious stones, relics, and a part of the true Cross disappeared from the cover of the book during the French revolution. See [Gregory Peroche], p. 62.

Let us cite the following passage from [Castellan, Vidan, p. 31]:

..Selon divers récits, l'Évangéliaire aurait servi lors du sacre des rois de France, notamment ceux de Francois II et Charles IV, puis d'Henri II, Louis XIII et Louis XIV qui "posèrent la main sur son texte en pronoçant la formule du serment" (L. Paris).

In 1485/46 a French pilgrim Gheorge Langherand wrote that in Zadar he heard a "Sclavonic" sermon, that is, a Croatian Glagolitic mass. In 1549 a French Franciscan and cosmograph Andre Thevet noted the prayer "Oce nas" (Our Father) in Croatian language. See [Raukar], p. 360.

According to the renowned Czech linguist Nemec, the influence that the Croatian glagolites in Prague had on the formation of orthography of the Czech language was "neither big nor negligible". The Polish king Vladislaw II Jagiello also opened a Glagolitic convent in Krakow (Kleparz) in 1390, where the Glagolitic priests were active for almost 100 years. His wife Jadviga was of the Croatian descent.

As a young man Charles IV visited for several days the Croatian coastal town of Senj in 1337, when he was only 21. In this important Glagolitic center, with the unique Roman Catholic cathedral where only the Glagolitic liturgy in Croatian Churchslavonic language had been served (instead of Latin rite), he made friends with the nobleman Bartolomej Frankapan. Frankapan supplied him with military escort on his journey to Tirol, where he was to meet his brother.

Zrin-Frankapan heritage in Croatia: 126

fortresses, castles and bourgs

There exist even earlier important traces of cultural contacts between Czechs and Croats, going back to 10th and 11th centuries. If you visit Prague, we recommend you to see the famous monastery in Sazava, just 60 km from Prague. There you can find the "Croatian room", describing in detail the presence of the Croatian glagolites in Czechia. For additional information see here.

It is worth noting that the famous Czech lexicographer Bartolomej z'Hlouce, better known as Kloret (14/15th centuries), wrote his Latin - Czech dictionary where Latin words are translated into Czech, while words of the Greek or Hebrew origin are translated - into Croatian! For example: sanctus -> svat, hagios -> svet.

The 14th century Czech philosopher Jan z'Holesova wrote in his tractate about the religious song "Hospodine, pomiluj ny" (= "God, have mercy on us", sung even today), that it contains many Croatian words (like hospodine = gospodine). Moreover, he even states that the Czech language and nation stem from the Croats: ...nos Bohemi et genere et lingua originaliter processimus a Charvatis, ut nostrae chronicae dicunt seu testantur, et ideo nostrum boemicale ydioma de genere suo est charvaticum ydioma..., see [Hercigonja, Povijest hrvatske knjizevnosti. II, p. 63].

A Czech chronicler Pulkava from 14th century (died in 1380) mentions that "to this day bishops, as well as priests, serve the Holly Mass and other rituals in their slavic language in Archdioceses and provinces of Split, Dubrovnik and Zadar." See [Strgacic].

Tri češke publikacije o samostanu Na Slovanech u Pragu

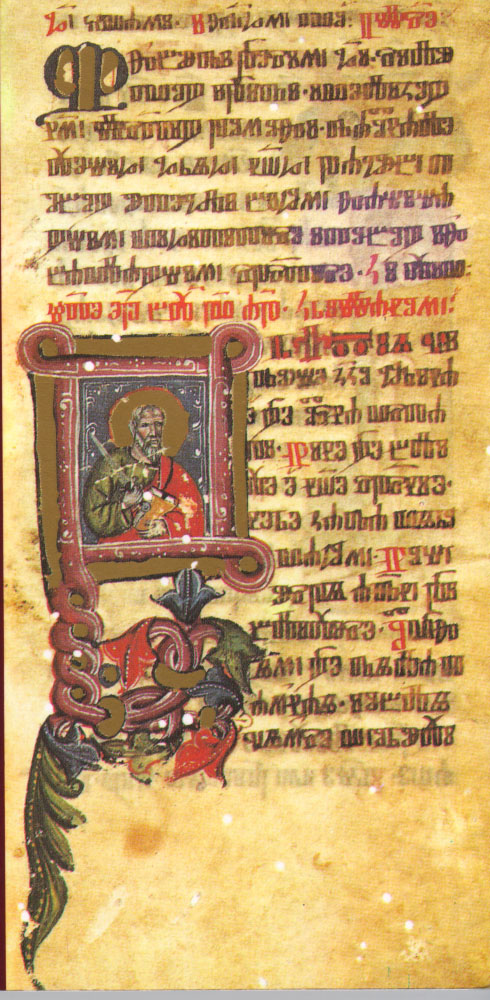

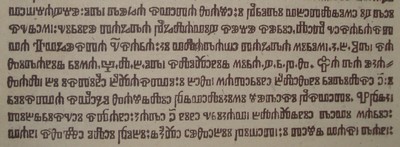

Fragment of a Croatian Glagolitic Psalter from the first half of the 14th century, brought from Croatia to the

Emaus Monastery in Prague, now kept in the Library of the National Museum (Narodni Muzeum) in the Czech capital.

The oldest known Croatian Glagolitic Bible is mentioned already in 1380 in a document from the Zadar archives which mentions "...una Biblia in sclavica lingua", see [Runje, O knjigama..., and his article in [Iskoni bje slovo, p 58, and Grbin's paper, p 116]. Unfortunately, we do not know if the Bible is preserved. From the same archives there is another testimony written in 1389, mentioning "unus libear Alexandri paruus in letter sclaua... Item unus Rimancius scriptus parrtim in latino, partin in sclauo".

An existing Glagolitic Bible is mentioned by the Italian scholar Giovanni Batista Palatino in his book from 1545.

We also know of another handwritten Croatian Glagolitic Bible prepared by Nikola Mojzes from the island of Cres. We know this from Primoz Trubar's foreword to Stipan Konzul's 1557 translation of the New Testament, see [Jembrih]. A Glagolitic Bible in possession of Bernardin Frankapan in the beginning of 16th century is mentioned in [Bratulic, Leksikon..., p. 150], and that were no news about its destiny. Was this the Zadar Glagolitic Bible?

A Croatian Glagolitic Bible had existed in the town of Beli on the island of Cres, according to a source from 1480 (see [Hercigonja, Povijest hrvatske knjizevnosti 2, p 84]). An inventory from 1624, written in Italian, describes the book as follows: "Una biblia, in schiavo in bergamina". According to [Stefanic, Determinante hrvatskog glagolizma, p 27], the minutes of visitations from 1579 and 1609 mention a Croatian Glagolitic Bible in Omisalj on the island of Krk. Many thanks to dr. Vesna Stipcevic for this information.

A Croatian

Glagolitic Missal written in the

It has been shown that very early systematic redaction of Croatian Church Slavonic Bible had existed already in the 12th century, see [J. Rienhart].

A

Croatian Glagolitic Dominican priest Beniamin

de Croatia,

born probably in Split,

participated in the preparation of Gennadij's

Bible, the oldest

Russian Bible (finished in 1499). He was the chief collaborator of the

Novgorod Archbishop Gennadij, where he spent about 20 years

(~1490-1510), at that time the capital of Russia. Beniamin translated

large portions from the Latin text of Vulgata into Russian (e.g. the

Book of Macabians, the Ezra sermons and some other). It is therefore

not surprising that some elements of the Croatian language can be

traced in this oldest Russian Bible. Beniamin translated also other

western books into Russian. Until his arrival Russia was in contact

almost exclusively with Byzantine culture. See [Gregory

Peroche], p. 69.

I

would like to thank academician Eduard

Hercigonja for bringing my attention to Beniamin. See [Horvat,

p. 17], and an article by academician

Zarko Dadic

Vladimir Rozov: Hrvatski dominikanac Venjamin u Rusiji ([PDF1], [PDF2]), Nastavni vjesnik, knj. 41, sv. 8-10, Zagreb, 1933, 302-336. See also here.

The Missal of Prince Novak from 1368 is considered as a rare and valuable monument of Croatian Glagolitic cultural heritage. It is kept in the Austrian National Library in Vienna. The book was written in Krbava (now a part of Lika). Many specialists say that this is the most beautiful Glagolitic book. Facsimile edition is planned to be published in the near future in Austria.

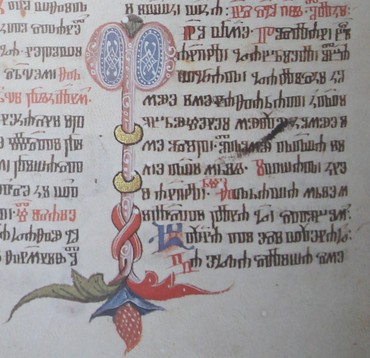

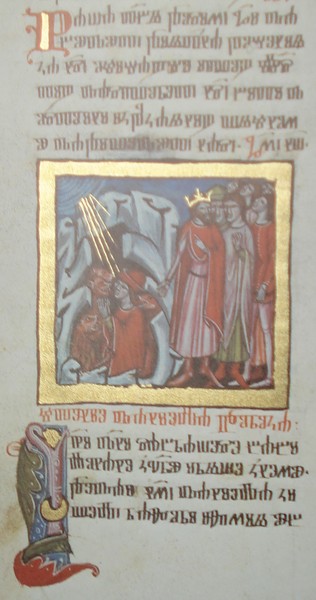

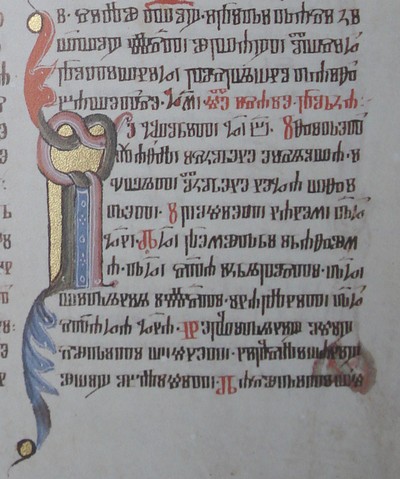

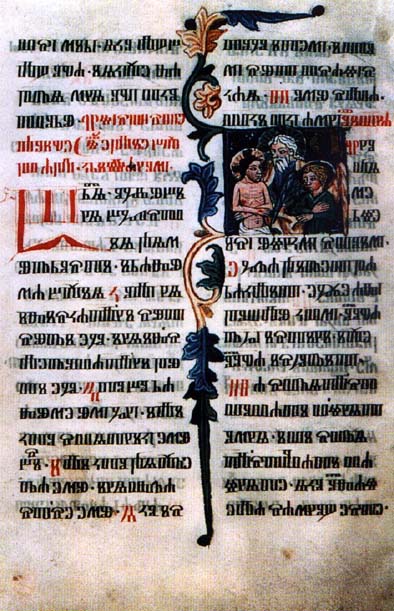

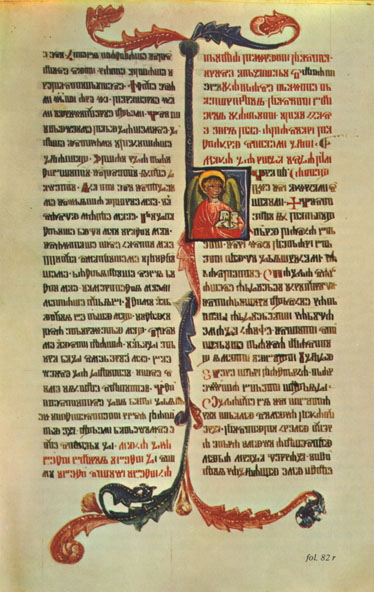

Probably

the most interesting Glagolitic book

is a liturgical book called Missal

of Hrvoje, written in 1404 by a

Glagolitic scribe Butko. It has 94 beautiful illuminations,

380 colourful initials

(some of them in gold), and many more small initials. Some initials

contain architectural elements of the city of Split. The book has been

kept in the Library of the Turkish sultans (Topkapi Saray) in

Constantinople since the 16th century. Once bound in precious covers

(with gold and precisous stones), from 19th century Hrvoje's Missal is

in leather binding. It is written in two columns on 488 pp (22.5x31

cm), and contains also some music notation.

Probably

the most interesting Glagolitic book

is a liturgical book called Missal

of Hrvoje, written in 1404 by a

Glagolitic scribe Butko. It has 94 beautiful illuminations,

380 colourful initials

(some of them in gold), and many more small initials. Some initials

contain architectural elements of the city of Split. The book has been

kept in the Library of the Turkish sultans (Topkapi Saray) in

Constantinople since the 16th century. Once bound in precious covers

(with gold and precisous stones), from 19th century Hrvoje's Missal is

in leather binding. It is written in two columns on 488 pp (22.5x31

cm), and contains also some music notation.

Some outstanding specialists (like Petar Runje and Eduard Hercigonja) believe that Hrvoje's missal was very probably written in Zadar, by a nobleman Butko pok. Budislava (i.e. son of late Budislav), born in the town of Nin, who lived in Zadar since the end of 14th century, see Runje's paper in [Iskoni bye slovo, p. 63]. Zadar at that time is a city of high European culture, see here. Butko mentions his own name in Hrvoje's missal on fol. 138, writing in the Glagolitic Script: "Tu pomeni žive, ke hoč, i Butka pisara" (Here, remember those alive, that you like, and Butko the scribe). On leave 161d (i.e., fol. 161 in the fourth column, or d-column) Butko advices an anonymous illuminator to draw figures of St. Doimo and St. Mihailo: "Svetago Duima i svetago Mihaila kipe piši". See [Stipcevic, knjiga I., p. 67]

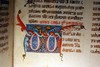

Missale

Hervoiae ducis Spalatensis Croatico-Glagoliticum

(yellow details on are made of golden leaves;

note a nice strawberry at the bottom of the above photo)

Hrvoje Vukcic Hrvatinic was the duke of Bosnia, a Croat who belonged to Krstyans (members of the Bosnian Church), a Christian religious sect about which we still know very little. Hrvoje also left us another very interesting book, Missal for Krstyans, written in the Croatian Cyrillic Script (ikavian dialect) by Hval in 1404, which is now kept in the University Library in Bologna. This beautiful book is a translation from the Glagolitic original. Moreover, Glagolitic letters can be found on two places.

|

V |

V |

On leaf no 140a on the right margin it is written in the Glagolitic Script: "Svetago Dujma i Svetago Mihovila kipe piši"

("Here, draw the figures of St. Duimo nad St. Michael").

This is Butko's hint to anonymous illumainator where to draw a picture of St. Duimo and St. Michael.

On leaf no 169a, in red ink, it is written: "Tu pomeni žive ke hoć' i Butka pisca"

(Here, mention those alive, as well as Butko the writer.)

Due to this, we know that the name of the writer of the Hrvoje missal was Butko.

According to Croatian researcher Josip Hamm, members of the Bosnian Church (Krstyans) particularly appreciated the Glagolitic Script: all the important Bosnian Church books (Nikoljsko evandjelje, Sreckovicevo evandelje, the Manuscript of Hval, the Manuscript of Krstyanin Radosav, etc.) are based on Croatian Glagolitic Church books.

Due to testimonies of Ivan Zovko written in 1899 we also know that Croatian women in Bosnia - Herzegovina had an old custom to embroider Crotian Glagolitic letters.

Here are some of very interesting Croatian Glagolitic monuments from Bosnia and Herzegovina that I scanned:

- two inscriptions

carved in stone tablet found in the

vicinity of Banja-Luka

(Slatina) from 1471:

- se pisa t(?) i l, ... ("this was written by...", a typical Croatian expression)

- se pi(s)a a? i (reference for both monuments is: [Poviest], see also [Fucic, Glagoljski natpisi -> Slatina]).

- from the Manuscript of Krstyanin Radosav, 15th century (a Glagolitic page from the book written in Croatian cyrillic; the book contains also Croatian Glagolitic Azbuka).

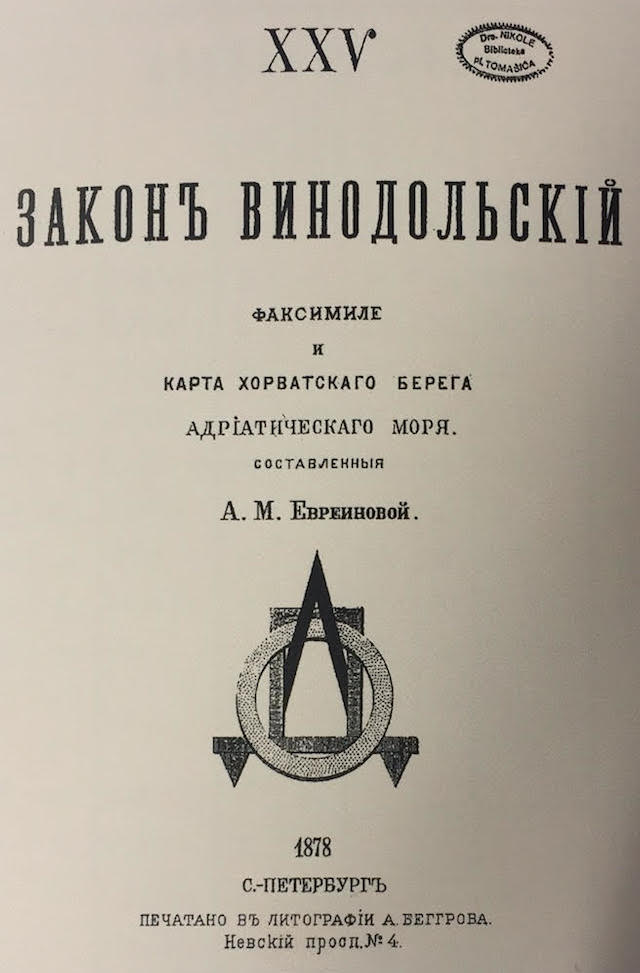

![]() t is

worth mentioning that some Russian monks

had been using the Glagolitic as a secret Script. The latest known case

dates back to the 17th century. Even today some children in Croatia use

it for the same purpose. And some of my students as well... Anna Evreinova

(1844-1919), born in a noble family in Sankt Peterburg in Russia, has

translated two important Croatian Glagolitic legal documents into

Russian: the Vinodol Code from 1288 and the Vrbnik Statute from 1388.

She has travelled along the Croatian coast. Also, she was the first

woman in Russia with PhD in Law. Source: Ana Cerovac: Ana Jevreinova,

"meštrica" koja je ruskoj javnosti predstavila Vrbnički statut, Vrbnički vidici, br. 58, Božić

2021., pp. 28-29.

t is

worth mentioning that some Russian monks

had been using the Glagolitic as a secret Script. The latest known case

dates back to the 17th century. Even today some children in Croatia use

it for the same purpose. And some of my students as well... Anna Evreinova

(1844-1919), born in a noble family in Sankt Peterburg in Russia, has

translated two important Croatian Glagolitic legal documents into

Russian: the Vinodol Code from 1288 and the Vrbnik Statute from 1388.

She has travelled along the Croatian coast. Also, she was the first

woman in Russia with PhD in Law. Source: Ana Cerovac: Ana Jevreinova,

"meštrica" koja je ruskoj javnosti predstavila Vrbnički statut, Vrbnički vidici, br. 58, Božić

2021., pp. 28-29.

Vinodol Code

facsimile

and

a map of Croatian coast

of Adriatic sea.

Composed by

A. M. Everinova

1878

S.-Peterburg

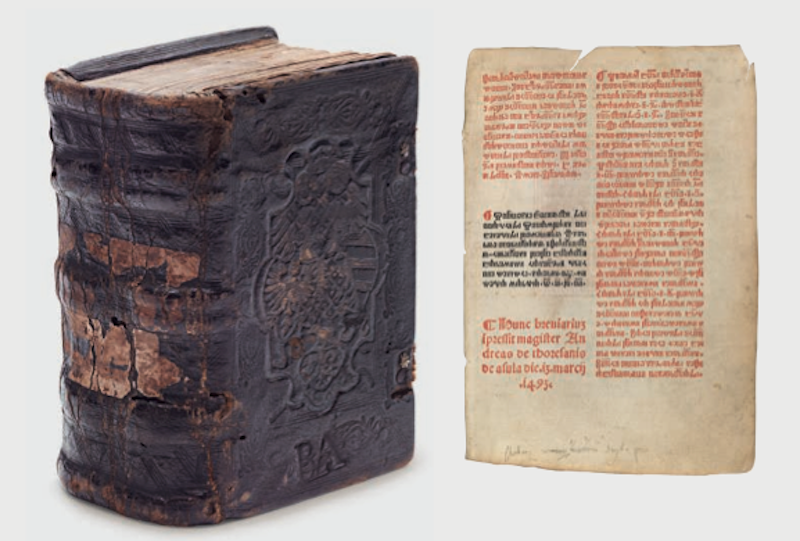

The

first Croatian

printed book in Glagolitic

letters appeared as early as 1483,

only 28 years after Gutenberg's Bible, 6 years after the first printed

book in Paris and Venice, one year before Stockholm, 58 years before

Berlin and 70 years before Moscow. It was a Missal

(440 pp,

19x26 cm), unfortunately it is not known where it was printed. The

Croatian Glagolitic Script was the fifth to appear in the history of

European printing, very soon after the Latin, Gothic, Greek and Hebrew

scripts. Twelve incomplete preserved copies of the first Croatian

incunabulum are

kept

in

The

first Croatian

printed book in Glagolitic

letters appeared as early as 1483,

only 28 years after Gutenberg's Bible, 6 years after the first printed

book in Paris and Venice, one year before Stockholm, 58 years before

Berlin and 70 years before Moscow. It was a Missal

(440 pp,

19x26 cm), unfortunately it is not known where it was printed. The

Croatian Glagolitic Script was the fifth to appear in the history of

European printing, very soon after the Latin, Gothic, Greek and Hebrew

scripts. Twelve incomplete preserved copies of the first Croatian

incunabulum are

kept

in

- The Library of Congress in Washington,

- in the Russian National Library in Sankt Peterburg,

- in the National Library in Vienna,

- in Apostolic Library in the Vatican (two copies),

- and in Croatia seven copies: six in Zagreb (2 in the Library of Croatian Academy HAZU, 2 in National and University Library, 1 at the Convent of St. Xavier of Franciscan Glagolitic Tertiaries, one in the City Library of Zagreb, contanining only 7 leaves), and one partially preserved copy in the Dominican Convent in the town of Bol on the island of Brač (near the city of Split).

The most preserved is the copy from the Berčić collection, kept in Sankt Peterburg. There are also seven fragments (pages) of the incunabulum, three of them printed on vellum. See [Nazor, Hrvatskoglagoljske inkunabule, 1993See [Nazor, Hrvatskoglagoljske inkunabule, 1993.] for more details] for more details. All 430 pp of the book can be scrolled via the web pages of the National and University Library, Zagreb, Croatia.

Monument in

honour of Johannes Gutenberg in Croatia's

capital Zagreb (carved by Dragutin Morak), in Jurisiceva street 7,

errected in 1887. One of rare

such monuments in the world. Moreover, it is the second such monument

built in honour of Gutenberg, after the one Mainz. Information by the

courtesy of Mr. Ivo Dubravcic.

The first incunabulum printed in the Croatian language and in the Latin Script was the Lectionary of Bernardin of Split, published in Venice in 1495. There is no doubt that it was created on the basis of earlier Glagolitic lectionaries.

Glagolitic books were printed not only in Croatia (Kosinj, Senj, Rijeka), but also in Venice, which had two Glagolitic churches at that time, and in Rome. Early Croatian printing becomes even more fascinating if we consider that at that time (by the end of the 15th century) invasions of the Ottoman Empire began. We know that the Croats participated in preparation of as many as 150 incunabula in Croatia and western Europe in the period between 1474 and 1500 (i.e. books printed during the earliest period of printing, 1455 - 1500).

There are altogether 71 printed Croatian glagolitic editions in the period from 1483 till 1812 (the so called old-printed glagolitic editions, which do not include Parcic's 1893 missal and several later editions, named so by [Kruming] - in Russian: staropecatnye glagoliceskie knigi). According to Kruming's classification, there are

- 6 incunabulae (15th century),

- 13 from the first half of 16th century,

- 16 from the second half of 16th century,

- 8 from the 17th century,

- 27 from the 18th century,

- 1 from the 19th century (1812).

- Kosinj, 1 (Kosinj breviary from 1491),

- Senj, 7 (1494-1508),

- Rijeka, 6 (1530-31),

- Bologna, 1 (1492, lost incunabulum), 1,

- Venice, 12 (1493-1561),

- Rome (The Vatican), 29 (1628-1812)

- Tübingen, 13 (protestant editions, 1561-1565),

- Nürenberg, 2 (protestant editions, 1561-1565).

Hrvatske glagoljičke inkunabule

The Russian National Library in St. Petersburg is in possession of important Bercic Collection of Croatian Glagolitic manuscripts and books from 13th to 18th century.

Let

us mention the name of Dobric

Dobricevic (Boninus de Boninis

de Ragusia), Ragusan

born on the island of Lastovo, 1454-1528, who worked as a typographer

in Venice, Verona, Brescia. His last years he spent as the dean of the

Cathedral church in Treviso. His bilingual (Latin - Italian) editions

of "Aesopus moralisatus, Dante's "Cantica" and "Commedia del Divino"

were printed first in Brescia in 1487, and then also in Lyon, France.

We know of about 50 of his editions, the greatest number belonging to

the period of 1483-1491 that he spent in Brescia - about 40. Croatia is

in possession of 19 of his editions in 30 copies. The greatest number

of his editions is in possession of the British Museum, London (22).

Another

Croat, known as Jacques Moderne,

born in Buzet (15th century), Istria, printed about 50 music booklets

in Lyon, France.

ccording

to the views of most Slavic scholars,

the Glagolitic Script was created by St. Cyrill in the second half of

the 9th century. Not all scholars agree on this point. Some of them

believe that it must have existed earlier, and that it had a natural

development over a much longer period. In any case, some of its letters

are quite close to the corresponding ones from very old oriental

scripts: South-Semitic, Samaritan (an old Hebrew Script), the Cretan

linear A and B, Armenian and others. Some are of the opinion that the

appearance of this Script in this part of Europe was due to extensive

migrations from the East. The question of the origins of the Glagolitic

Script seems to be still a difficult open problem. In the earliest

period it also existed in Ukraine, Bulgaria and Macedonia, but only

until the 12th century, when the Cyrillic Script (which is essentially

a Greek Script) became predominant.

ccording

to the views of most Slavic scholars,

the Glagolitic Script was created by St. Cyrill in the second half of

the 9th century. Not all scholars agree on this point. Some of them

believe that it must have existed earlier, and that it had a natural

development over a much longer period. In any case, some of its letters

are quite close to the corresponding ones from very old oriental

scripts: South-Semitic, Samaritan (an old Hebrew Script), the Cretan

linear A and B, Armenian and others. Some are of the opinion that the

appearance of this Script in this part of Europe was due to extensive

migrations from the East. The question of the origins of the Glagolitic

Script seems to be still a difficult open problem. In the earliest

period it also existed in Ukraine, Bulgaria and Macedonia, but only

until the 12th century, when the Cyrillic Script (which is essentially

a Greek Script) became predominant.

The earliest Croatian Glagolitic monuments until the 12th century

inclusively

The Glagolitic Script

began to acquire a

new, angular

form in the 12th century,

usually referred to as the Croatian

Script. The round form

was also present on earliest

Croatian Glagolitic monuments. Let us list more than 30 of the most

important Croatian Glagolitic documents written in the round Glagolitic

or round/angular Glagolitic in the earliest period (11th and 12th

centuries). First those written on parchment:

The Glagolitic Script

began to acquire a

new, angular

form in the 12th century,

usually referred to as the Croatian

Script. The round form

was also present on earliest

Croatian Glagolitic monuments. Let us list more than 30 of the most

important Croatian Glagolitic documents written in the round Glagolitic

or round/angular Glagolitic in the earliest period (11th and 12th

centuries). First those written on parchment:

- the first of the Kiev Folia - which has been written in the Dubrovnik region (11th century), as proved by dr. Agnezija Pantelic;

- Sinai folia from 11th century, used in the Dubrovnik region, see dr. Agnezija Pantelic in [Badurina, pp. 101-111] and [O Kijevskim i Sinajskim...],

- the Vienna Folia (11th century), (see the photo on the right),

- the Glagolita Clozianus (11th century),

- the Budapest fragments (11/12th centuries),

- the Grskovic fragment of Apostle (12th century),

- the Mihanovic fragment of Apostle (12th century),

- the Baska ribbons (12th century),

- the Ljubljana homiliary, fragment of a breviary (12th century),

- the Split fragment (12/13th centuries),

- the muniment of the `famous Dragoslav', (parchment or paper, preserved in later transcript) January 1, 1100, the earliest mention of the towns of Vrbnik and Dobrinj on the island of Krk,

- Vrbnik fragments (1 and 2) of a church book, 12th century, (see Ivan Bercic's "Citanka staroslavenskog jezika", 1864, Prague, or Vjekoslav Spincic's "Crtice iz hrvatske knjizevne kulture Istre", 1926, reprinted by KS, Zagreb 1984),

- the Vrbnik fragment of a breviary, 12th century (ibid.)

- the Krakov fragment, 12th century (see Eduard Hercigonja, his article in [Croatia and Europe], volume I, p 390])

- the Selce

fragment, 12th century?,

see Josef Vajs,

As shown by dr. Agnezija Pantelic, Kiev and Sinai folia were used used in the Dubrovnik Diocese by the end of 11th century (see [O Kijevskim i Sinajskim...]. The rest are 18 inscriptions from the 11-12th centuries, carved in stone in the round or the round/angular Glagolitic. It is of interest to stress that Glagolitic monuments carved in stone exist only among the Croats (in today's Croatia and parts of BiH), nowhere else. For more information see Croatian Glagolitic heritage in the region of Dubrovnik.

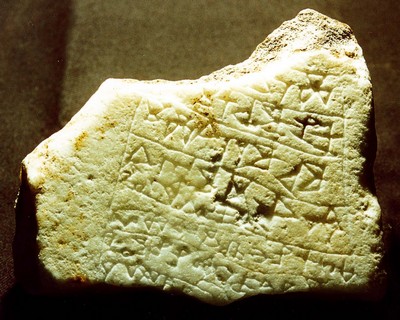

- the Valun tablet (11th century; Istria; according to dr. Marica Cuncic from 10th century, personal info.),

- the Plomin tablet (11th century; Istria; according to dr. Marica Cuncic from 10th century),

- the Krk tablet

(11th

century; according to dr. Marica Cuncic

from 10th century),

Krk Tablet from the 11th century (according to Marica Cunicic, 10th century)

On the photo Mrs. Mirna Lipovac.

- the Konavle fragment,

(1060 or

later in 11th century), discovered in the region of Konavle

south of Dubrovnik in 1997 (see

also Croatian

Glagolitic heritage in the

region of Dubrovnik),

- the Zupa Dubrovacka

fragment

(10th or 11th century), found in Zupa dubrovacka near the city of Dubrovnik

in 2006 (see [Zeravica])

- the Baska tablet (end of 11th century),

- the Baska fragments (end of 11th century), remains of the second Baska tablet,

- the Senj tablet (end of 11th century),

- the Kijevci fragment (11/12th centuries), north - western Bosnia,

- the Kukuljevich tablet (1095), lost, but its content is known (western Slavonia, between Lipovljani and Novska);

- the Brodski Drenovac stone inscriptions, western Slavonia, according to my estimate the oldest parts belong to 12th century; proof: trapesoidal yat appearing on several places, vaulted Glagolitic D with two eyes, the famous triangular A as on the Baska tablet (on a stone tablet in the church of Sv. Dimitrije, obivously transferred from an older church);

- the Grdoselo fragment (11/12th centuries; Istria),

- the Supetar fragment (Sv. Petar u Sumi, i.e. St. Peter in the Wood, Istria, 12th century),

- the Knin fragment (11/12th centuries),

- the Plastovo fragment (11/12th centuries),

- the Hum graffitto (Istria, 12th century),

- the Roc abecedarium (Istria, approx. 1200),

- the Gradac tablet (2nd half or 12th ct. or 1st half of 13th ct., near Drnis)

- the Humac tablet (12th century), Herzegovina.

It is possible that the following monuments should be added to the above list:

- the Marian Evangel (end of 10th century; its provenance is still not clear - Bulgarian specialists think it is of the Bulgarian origin),

- the Paris Glagolitic abecedarium (sometimes called "Bulgarian" in the literature),

- the München abecedarium,

- the Rudina inscription (12th century, western Slavonia on the North of Croatia).

- the Sveti Kriz fragment (12-13th century) found near Trsat, Rijeka, in 2004.

Source: [Dekovic, Svetokrizki odlomak]

The above list shows that the name ``Bulgarian Glagolitic'' or ``Macedonian Glagolitic'' for the oldest form of the Glagolitic Script is not fully justified.

The Split fragment of the Glagolitic missal, dating from the 12/13th century,

according to Slavko Kovačić has been written in the Split Archdiocese.

Investigations of the oldest forms of the Glagolitic Script performed by Dr. Marica Cuncic in her Ph.D. thesis (1985) have led to the discovery of triangular form of the Glagolitic (with triangular shapes occurring in most of the letters), dating from the 9th and 10th century. Its remnants can be found in the Croatian Glagolitic inscriptions - for example on the Valun tablet, Krk tablet, and Plomin tablet (from the islands of Cres, Krk and Istrian peninsula respectively, all from 10th century according to dr. Cuncic), and also on some other oldest Croatian Glagolitic monuments. By transforming the triangles into circles the round type has developed. All three forms can be seen on the Baska Tablet (Bascanska ploca), also in handwritten books as well as in printed books. Hence, the Glagolitic script evolved from the triangular form:

- Triangular Glagolitic (9-10th centuries),

- Round Glagolitic (11-12th centuries),

- Angular Glagolitic (13-19th centuries).

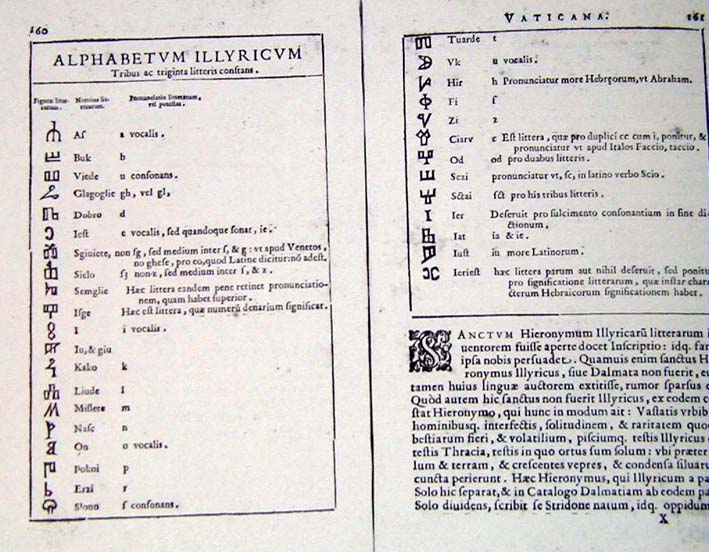

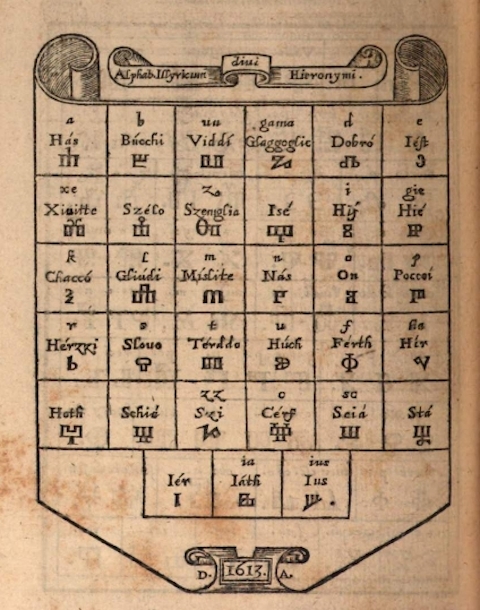

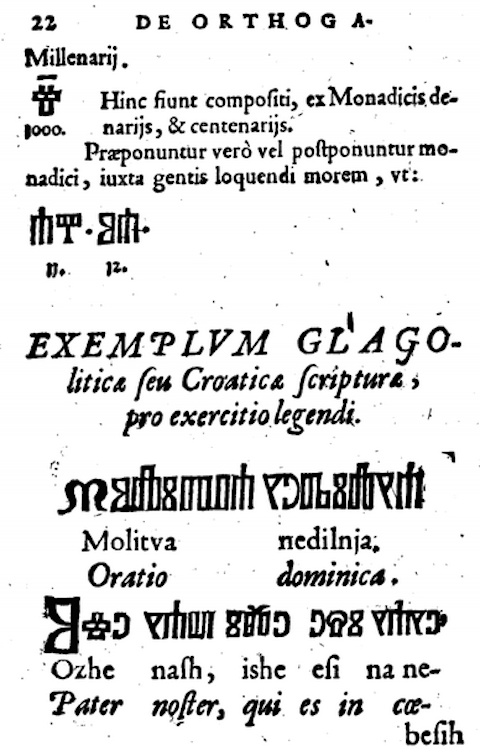

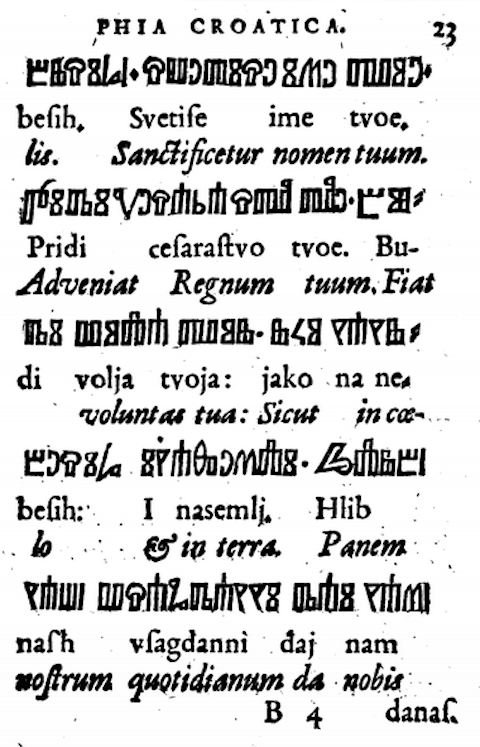

Several outstanding European scholars mention Croatian Glagolitic script in their books already in 16th and 17th centuries:

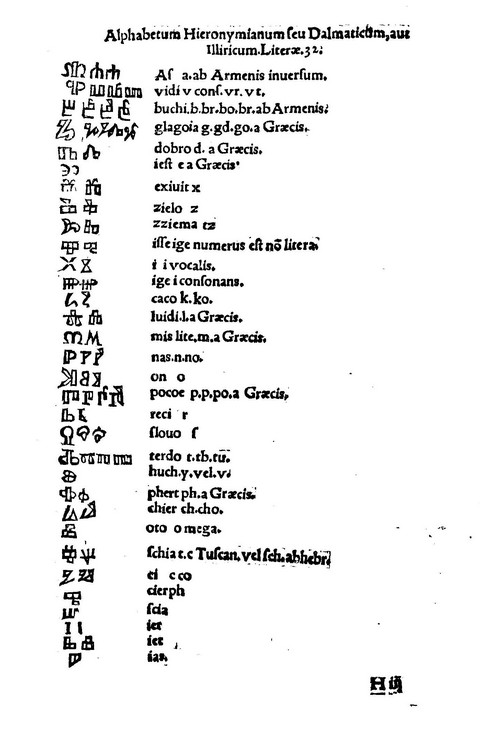

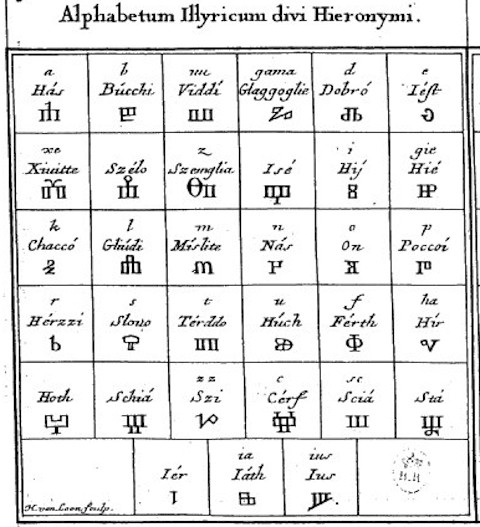

- Renowned

French polyhistorian and encyclopaedist Guillaume

Postel included a table of Croatian Glagolitic Script (which he

calls Alphabetum

Hieronymianum seu Dalmaticum, aut Illiricum)

in his book Linguarum

duodecim characteribus differentium alphabetum

([pdf]

at Bibl. Nationale, Paris) published in 1538.

According to Eduard Hercigonja, this represents the first mention of

Croatian Glagolitic in West-European printed literature. Here is

Postel's Glagolitic table, [pdf],

or see below:

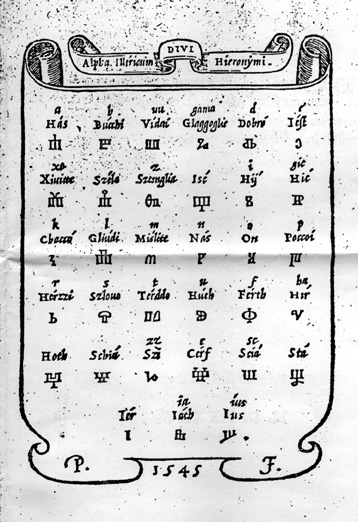

- In

1545, in Rome, an Italian encyclopaedist Giovanni

Batista Palatino presented the

Glagolitic Script in the second

edition of his book Libro

Nouvo (Libro nel qual s'insegna a

scrivere ogni sorte lettera, antica et moderna...),

among 29

scripts that he designed for printing. He claims the Glagolitic (which

he calls Buchuizza

- bukvica) to be created by St. Jerome, and

"different from all other existing Scripts".

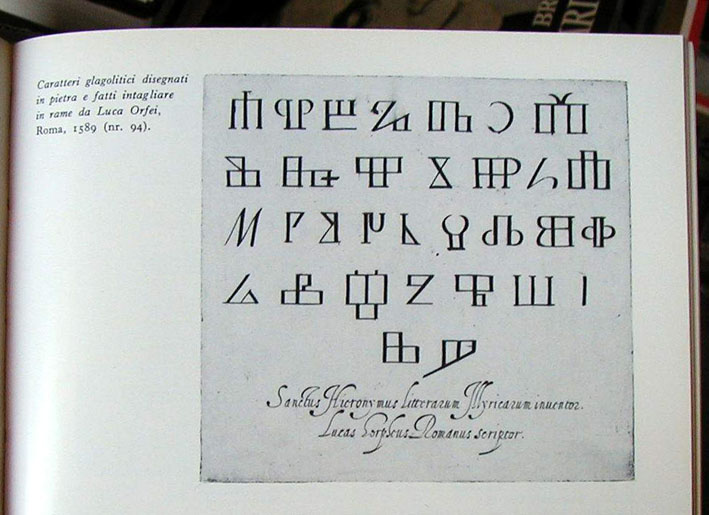

Gianbatista Palatino also mentions that there are numerous breviaries and missals written in the glagolitic, including the Glagolitic Bible (...et anco la Biblia). In the book a Croatian cyrillic is also exhibited, with the inscription on the tombstone of the Bosnian Queen Katarina (15th century). - Luca

Orfei

created a set

of Croatian glagolitic caracters in Rome in 1589 (Caratteri glagolitici

disegnati in pietra e fatti intagliare in rame da Luca Orfei, Roma,

1589, nr 94). Note that the order letters is AZ VIDI BUKI..., instead

of the usual AZ BUKI VIDI... (the same mistake is contained in the

table of Guillaume Postel). It seems that Luca Orfei copied the

glagolitic table from Postel.

For more information see the monograph "Tre Alfabeti per gli Slavi", 1985, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana. - In

1591 an Italian scholar Angelo

Rocca (founder of Angelica

Library at Rome) wrote a book where

Glagolitic Script is included (A. Rocca: Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana

a Sixto V... translata, Roma, 1591: Alfabeto glagolitico).

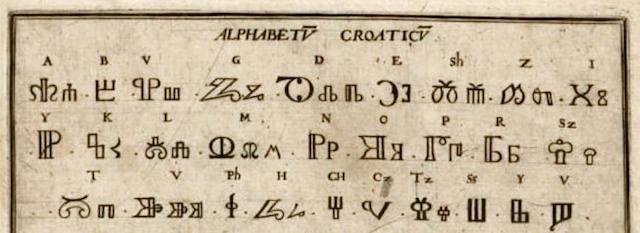

- Brothers de Bry

(Johann Theodor

and Johann

Israel de BRY) published a luxorous book Alphabeta et

Characteres, iam. inde a creato mundo ad

nostrausq. tempora, apud omnes omnino nations usurparii; ex variis

auto: ribus accurate depromptii. Frankfurt, 1596.

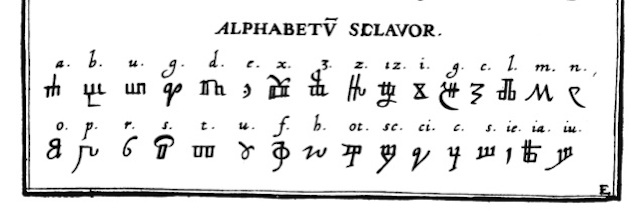

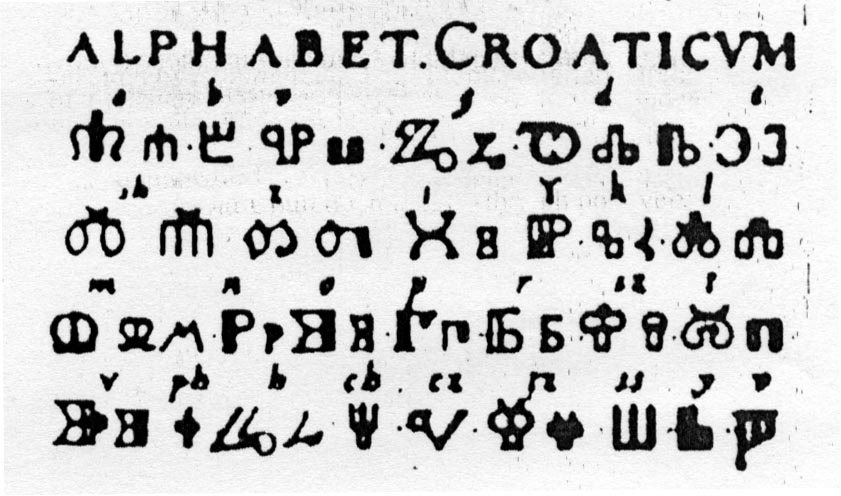

Among the alphabets represented are Syrian, Phoenician, Hebrew, Egyptian, Arabic, Sumerian, Greek, Slavic, Croatian, Russian, Armenian, Indian, Visogothic and a multitude of Roman alphabets. Here is Alphabetum Croaticum (note that zelo, iže, ot, jer and jest-je are omitted from the table):

Brothers de Bry call this script "Alptum Slavorum", but this is in fact also "Alphabetum Croaticum" as in the above table. See [Kempgen].

- Mavro

Orbini, Croatian historian and

Benedictine priest, in his book Il

regno de gli Slavi, Pesaro

1601, provided the description and the table of the Croatian Glagolitic

script (called Buchuiza)

and of the Cyrillic (called

Chiuriliza). However, one has to be very cautious with interpretations

of its content (see [Gavran,

IV]). We

mention in passing that he also issued Ljetopis

popa Dukljanina, one of the

oldest Croatian literary texts and

historiographical chronicles, dating from 12th century. Orbini's other

work concerning the history of Bulgarians represents the beginnings of

modern historigraphy of this nation.

- Claude Duret,

French scholar, is the author of the book Thrésor de

l'histoire des langues de cest Univers (1078 pp), published

in

1619, which

contains two tables of Croatian glagolitic, and we show one of them (on

p. 740):

The second table is here (on p. 739): [JPG]. In his book he cited Giovanni Batista Palatino's description of the Glagolitic, and translated it into French (see [JPG]): "... & ont en icelui leurs Messels, Breuiares, & Offices de la nostre Dame, & encor la Bible". On p. 744 one can find Lord's Prayer in Croatian (see [JPG]). See [Kempgen].

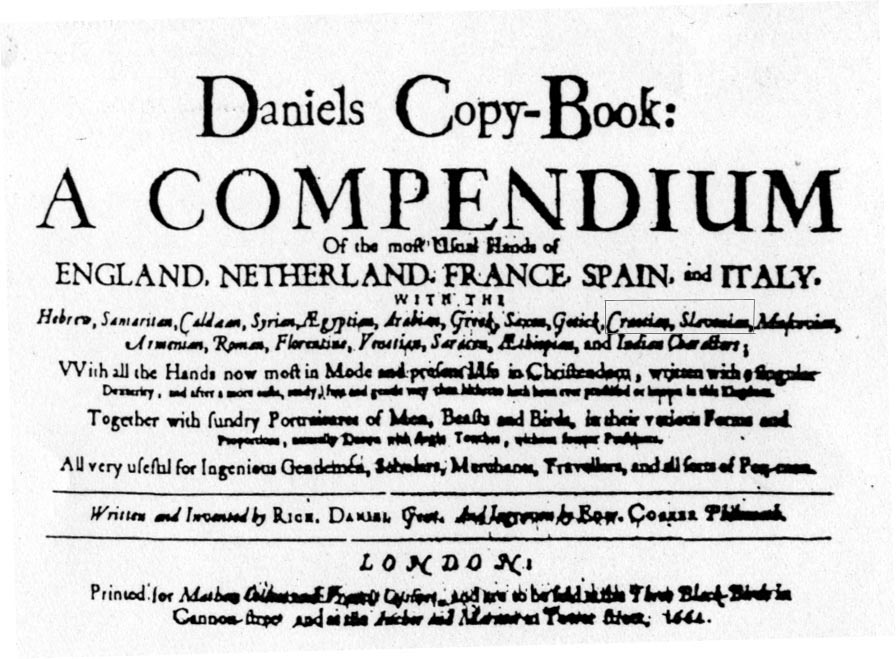

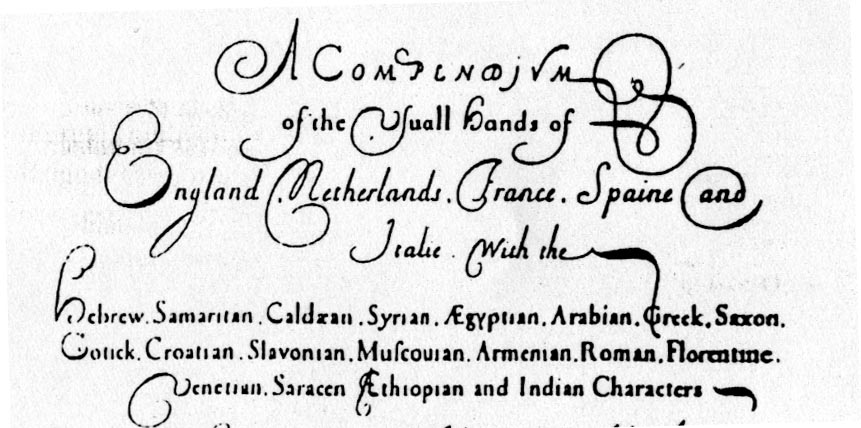

- It

is interesting

that a table of the Glagolitic Script was included as early as in 1664

in a book prepared by Richard

Daniel and published in London.

It represents a catalogue of various Scripts in use in the Christian

world. The Glagolitic Script presented there is called expressly the Croatian

hand or Alphabetum

Charvaticum. The book contains

also the

table of Croatian

glagolitic quick-script,

which Daniel calls Sclavorum

Alphabetum, and Croatian - Bosnian

cyrillic

(many thanks

to Professor Ralph

Cleminson for this information).

The book is

entitled

Daniels Copy-Book: or, a Compendium of the most usual hands of England, Netherland, France, Spain and Italy, Hebrew, Samaritan, Caldean Syrian, Aegypitan, Arabian, Greek, Saxon, Gotik, Croatian, Slavonian, Muscovian, Armenian, Roman, Florentine, Venentian, Saracen Saracen, Aethiopian, and Indian characters; with all the hands now most in mode and present use in Christiendom... See [Franolic] and also [Kempgen].

Here are two parts of the title page of Daniel's Copy-Book:

- A small table containing twelve Glagolitic and Cyrillic letters was provided by Ivan Tomko Mrnavić in his book Nauk Karstianski (Christian Science, published in Latin and Croatian languages in left and right columns respectively), Rome, 1708.

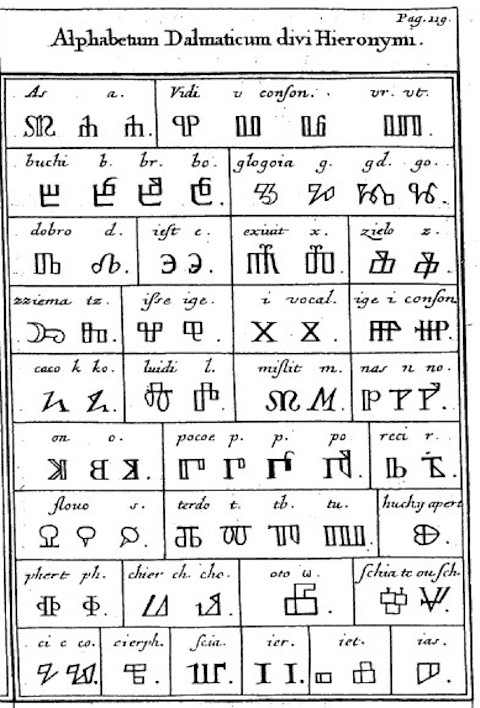

- Anselmo

Banduri (Dubrovnik,

1675 - Paris, 1743), Ragusan

benedicine monk, archaeologist, paleorgrapher and antique numismatics

expert,

discusses Croatin Glagolitic Script in his book Imperiorum

oriental, sive Antiquitates Constaninopolitanae, Vol II

(Vol II contains also De

Administrando Imperio by Constantin

Porphyrogenetus, as well as two tables of Croatian Glagolitic Script

just following

p. 119; Bibliotheque Nationale Paris), published in Paris

in 1711. See these two tables below.

The above table is very close to the one provided by Guillaume Postel in 1538 in Paris, and Banduri follows his mistake concerning the order order of glagolitic letters (A V B..., instead of A B V...). The table below (appearing on the same page 119 of Banduri's voluminous book, Vol II) corresponds to the the one provided by Giovanni Battista Palatino (Joannes Palatinus) in 1545 (with the analogous accompanying comment - written in Italian, that there are numerous breviaries and missals written in the glagolitic, including the Glagolitic Bible - ... et anco la Biblia; see the and of p. 118 and the beginning of p. 119 of Banduri's monograph).

Many thanks to Mrs. Biserka Krslin Barda (Paris) for her kind information.

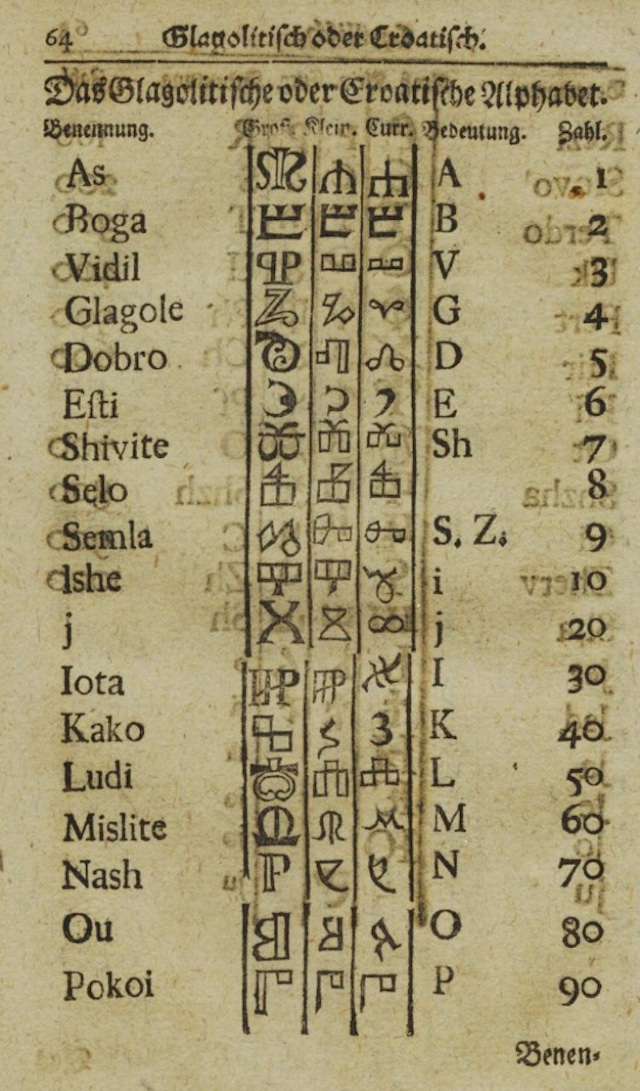

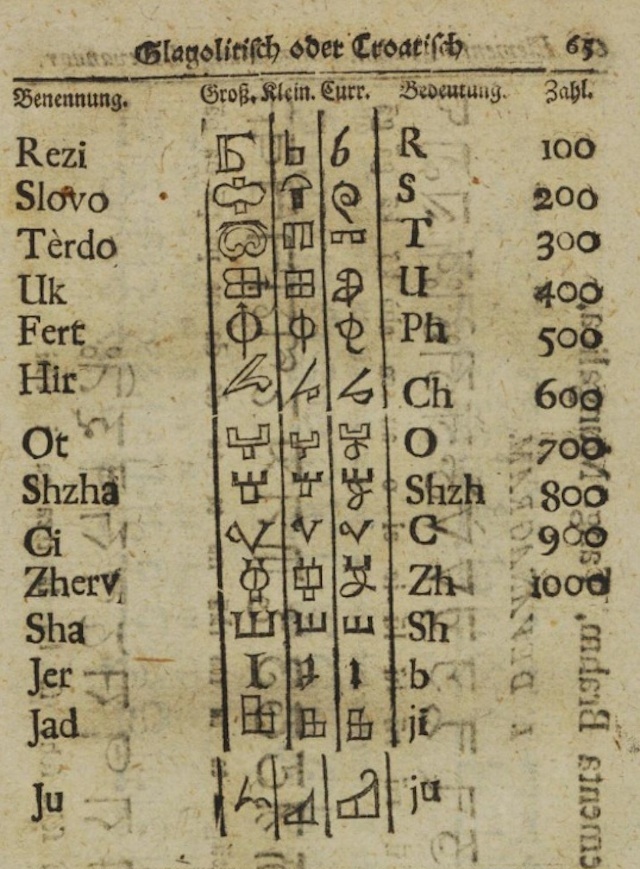

- Johann Friedrich Fritz, Neu

eroͤffnetes in Hundert Sprachen bestehendes A.b.c. Buch, Oder

Gruͤndliche Anweisung, In welcher Der zarten Jugend nicht allein in der

Teutsch, Latei- nisch, Franzoͤsisch, Iͤtaliaͤnischen, etc. sondern auch

zu denen meisten Orientalischen Sprachen, deren Erkanntniß und

Aussprache in kurtzer Zeit zu lernen, Ein leichter Weg gezeiget wird.

Leipzig, bey Christian Friedrich Geßner, 1743. – Available

online. Note that Fritz uses the following terminology:

Glagolitisch oder Croatisch (i.e., Glagolitic or Croatina Script). The

reader will also notice several mistakes in the table. See [Kempgen].

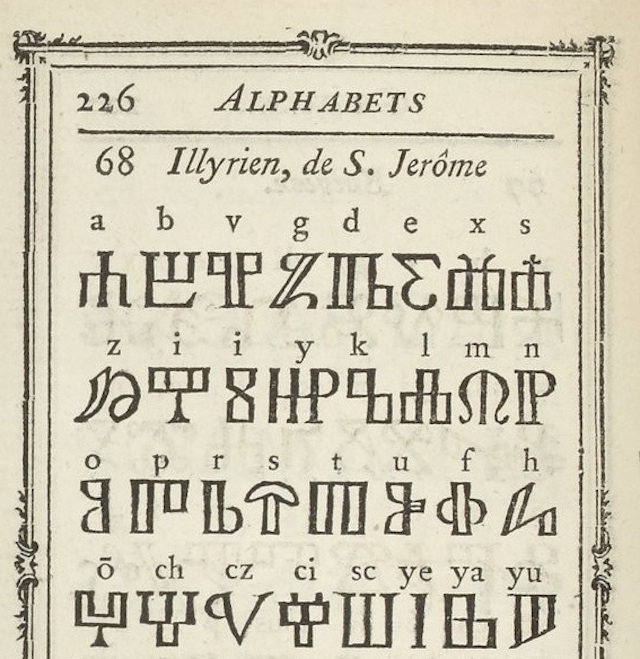

- The French Encyclopedie

by Diderot and D'Alambert

from 1751 has a table and a short description

of the Glagolitic script, called Ilyrien

ou Hieronimite (in

section Alphabets anciens). This enabled wide European cultural circles

to be better acquainted with this exotic script (...Les

caracteres

illyriens sont singuliers et on y remarque trés peu de

rapport

avec les alphabets que nous connaissons...).

For more information

see [Hercigonja:

Na temeljima hrvatske

knjizevne kulture, pp 49-56]. The photos of the Croatian glagolitic

table in the French Encyclopedia can be seen here.

- Pierre Simon Fournier, Manuel

typographique, utile aux gens de lettres, & à ceux qui exercent

les différentes parties de l’Art de l’Imprimerie. Par Fournier,

le jeune. Tome II. A Paris, Chez l’Auteur, rue des Postes. J. Barbou,

rue des Mathurins. MDCCLXVI. [1766].

- A short note about Croatian Glagolitic and Cyrillic (see below) can be found in Viaggio in Dalmazia by Alberto Fortis, Venice 1774. The book is also known to have brought the famous poem of Asanaginica to European public. See also at the Croatian Cyrillic web page.

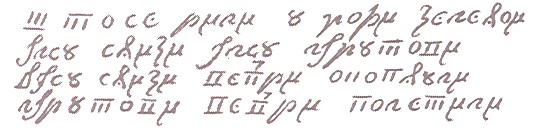

Sto

se bili u gori zelenoj?

Al su snizi al so labutove?

Da su snizi vec bi okopnuli;

Labutove vec bi poletili.

Here is the same text in Croatian Cyrillic quickscript (with slight differences):

Sto

se bili u gori zelenoi

Al su snizi al su labutovi

Da su snizi vec bi okopnuli

Labutovi vec bi poletili

In 1584, Slovenian grammarian Adam Bohorič published his most important book Arcticae horulae succisivae (Free Winter Hours) in Wittenberg in Germany in the Latin language, in which there is a table of Croatian Glagolitic Script. Its characters are called Croatian or Glagolitic letters, with a detailed presentation of this script:

Literae Croaticae seu

Glagoliticae.

More extensive information about Croatian Glagolitic introduction

contained at the beginning of the Bohorič grammar from 1584.

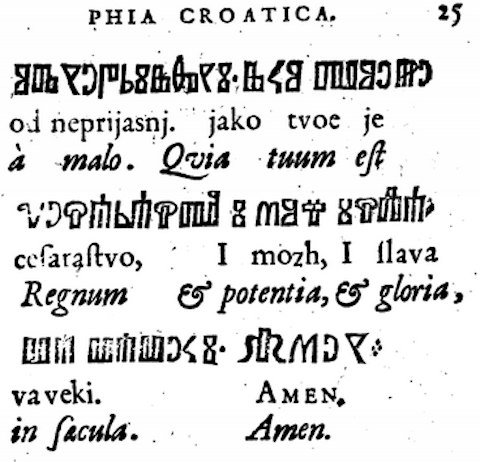

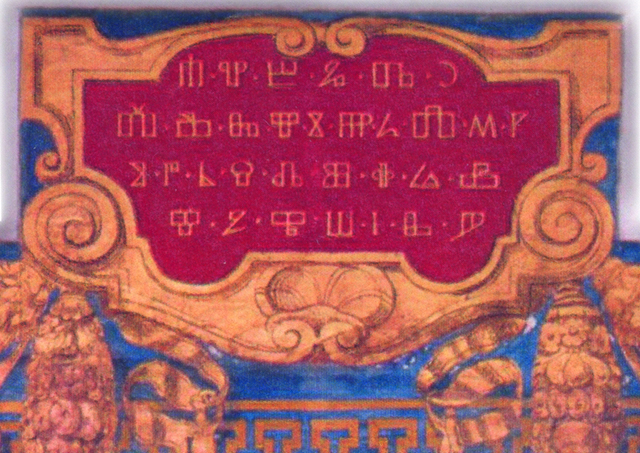

Sala Sistina (the Sixtine Hall) in the Vatican Library,

with the figure of St. Jerome on the right (the first column, with blue

background), containing the table

of the Croatian Glagolitic Script above his head (on red background).

Note a lion by St. Jerome's right leg.

The table of the Croatian Glagolitic Script above the head of St. Jerome

It starts with AZ VIDI BUKI..., instead of the usual AZ BUKI VIDI...

The same order of glagolitic letters can be found in the Croatian

Glagolitic table of the

French scholar Guillaume Postel published in 1538, as well as in the

table of

the Italian scholar Luca Orfei published in 1589.

The fresco of St. Jerome in the Vatican

Library was ordered by Pope Sixto V, and was completed in 1589.

(Many thanks to Daniel Premerl, PhD, for this information.)

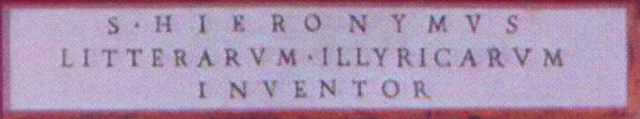

S. Hieronymus Litterarum Illyricarum Inventor

i.e., St. Jerome - inventor of Illyric letters, that is, of the

Croatian Glagolitic Script.

Many thanks to Darijo Tikulin for sending me the above two photos,

issued as a part of the front cover of his book

"Libri iz armaruna moga dida Mate maranguna", Zadar 2018., published by

Društvo zadarskih Arbanasa.

Lit. Daniel Premerl: „Sanctus Hieronymus litterarum illyricarum inventor“ – ikonografija svetoga Jeronima kao tvorca glagoljice, Kroatologija, Vol. 13 No. 3, 2022., str. 53-75 (and especially pp 56-63)

The Croats possess an extensive collection of more than 800 legal documents, statutes etc., written in the vernacular between 1100 and the end of 16th century - more than any other Slav nation. This extremely important collection of muniments called Acta Croatica (or listine hrvatske) represents a rich source for the study of the Medieval Croatian language. Most of the documents are written in Glagolitic, some also in Croatian Cyrillic and Latin. "Acta Croatica" is to be published by the Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts. The first two incomplete editions were published in 1863 and 1898.

The Croatian Glagolitic Script has hundreds of extraordinary ligatures, resembling real buildings, connecting two, three and sometimes even four or five letters. They had been in extensive use in both handwritten and printed books, and especially in the Croatian Glagolitic quick-script. The Brozich breviary alone, which is a printed book (1561), contains as many as 250 different ligatures. The Croatian Glagolitic Script has very probably more ligatures than any other script in history.

Some of the Croatian Glagolitic ligatures. Source Rjecnik crkvenoslavenskoga jezika jezika

(Dictionary of Croatian Church-Slavonic Language), technically modified

by Marko Csenar, Zeljezno / Eisenstadt, 2010.

The broken ligatures created by Blaz Baromic (14/15th centuries) represent a unique phenomenon in the history of European printing. The idea was to add one half of a letter to another. This possibility arose from the architecture of Glagolitic letters. Broken ligatures appear in two incunabula: the Baromic breviary printed in Venice in 1493, and the Baromic missal printed in the Croatian city of Senj in 1494. When looking at their pages, one has the impression as if they are handwritten. It is fascinating that the Senj printing house had been active despite the onslaughts of the Turkish Ottoman Empire.

€ 57,000-85,000

Who is the proprietor of this Croatian incunabulum?

We

know of altogether five

Croatian Glagolitic incunabula,

whose samples are kept in Zagreb,

Washington, the Vatican, St Petersburg, Schwarzau, München,

Budapest, Venice, Sibiu

(Roumania), plus one lost incunabulum (from

1492, written by Matej Zadranin). In the period between 1483 and 1561

altogether 21 titles of printed Glagolitic books were issued. The lost

1492 incunabulum (Ispovid opcena) was printed in Bologna, as we know

from the note written in the Tkon collection from ¨1520.

esides

of city of Senj, Zadar was also an

important Glagolitic center during centuries. It is interesting that in

numerous Zadar churches - St Marija, St Donat, St Stjepan, St Mihovil

and other - also the Glagolitic mass was served besides Latin. The same

is true even for the Zadar cathedral of St Stosija. See [Runje].

esides

of city of Senj, Zadar was also an

important Glagolitic center during centuries. It is interesting that in

numerous Zadar churches - St Marija, St Donat, St Stjepan, St Mihovil

and other - also the Glagolitic mass was served besides Latin. The same

is true even for the Zadar cathedral of St Stosija. See [Runje].

Thousands of books were printed in the Croatian Glagolitic and some in the Croatian Cyrillic Script during the past centuries, many of them with the generous help of Croatian Protestants who were active in Wittenberg and Urach in Germany in the 16th century. About thirty books were printed in 25,000 copies between 1561 and 1565, 300 of which have been preserved. On the front page of the Glagolitic Cathecismus prepared by the Croatian Glagolitic priest Stipan Konzul from Istria and printed in the German city of Tübingen in 1561, it is explicitly stated to be written in the Crobatischen Sprach (Croatian language). It is interesting that several editions were printed for Italians living in Istria (of course, in Italian and in the Latin script).

The last Croatian Glagolitic book (Missal) was printed in Rome in 1905.

It is little known that a rescript of Austrian-Hungarian King Ferdinand I (1515-1564) granted the Burgenland Croats in Austria, who had to escape before the Turks, the right to choose their own priests who practiced God's service in Croatian vernacular language, and with holly books written in the Glagolitic. This privileges had been cancelled after his death, and since 1569 the Glagolitic was officially forbidden in Croatian parishes in Burgenland in Austria (Gradisce). See Miroslav Vuk-Croata: Hrvatske Bozicnice, HKD Sv. Jernoma, Zagreb 1995, p. 167.

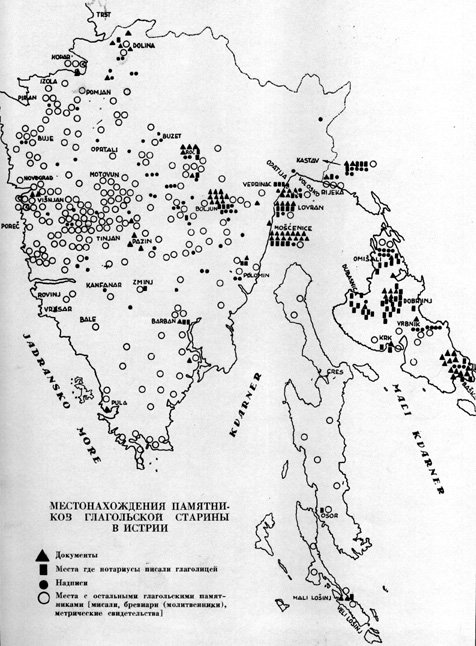

The Glagolitic alphabet represents maybe the most interesting cultural monument of Croatia. Our Glagolitic books (written and printed) and other Glagolitic monuments are scattered in many national libraries and museums of the World, in as many as 27 countries, in nearly 80 cities outside of Croatia:

|

|

The New York

Missal, 1400-1410

written in the

region of Zadar or Lika-Krbava,

now in the

possession of the Pierpont

Morgan Library in New York.

Reprinted by Verlag Otto Sagner Verlag

(Munich) in 1977 with an introduction by Henrik Birnbaum (USA).

PROVENANCE:

Zadar or Lika-Krbava region.

Frederick North, fifth Earl of Guilford (1766-1827), with his

bookplate; his sale, Evans, 1830, bought by Thorpe for Sir Thomas

Phillips. The underbidder was probably Sir Frederic Madden, for the

British Museum. Phillips paid the colossal price for this manuscript at

the Guilford sale, and considered it one of his chief treasures. It was

often produced at his "desserts of manuscripts" for the admiration of

visitors. This codex was considered by Sir Thomas Phillips to be one of

his chief treasures. In 1966 it was bought by the Pierpont Morgan

Library, New York. For more information see Croatian

Glagolitic in the USA, [Birnbaum],

and a monograph (extended doctoral dissertation) written by Andrew

Corin: The

New York Missal: A Palaeographic and Phonetic

Analysis, 272 pp, 1991, UCLA,

Los Angeles, USA. Corin's analysis

shows that the book was written by at least 11 scribes, members of a

large, unknown glagolitic scriptorium.

edieval

religious plays were performed in

Croatian cities and towns on the squares in front of churches, like in

Western Europe. The first secular dramas were presented in Zagreb and Vukovar

as early as the 14th century (in the Croatian language, written in the

Latin Script). Some of the earliest preserved stage instructions

written in the Glagolitic Script come from the island of Pasman near Zadar.

edieval

religious plays were performed in

Croatian cities and towns on the squares in front of churches, like in

Western Europe. The first secular dramas were presented in Zagreb and Vukovar

as early as the 14th century (in the Croatian language, written in the

Latin Script). Some of the earliest preserved stage instructions

written in the Glagolitic Script come from the island of Pasman near Zadar.

You can see more about some outstanding Croats in the Middle ages who used the Glagolitic Script:

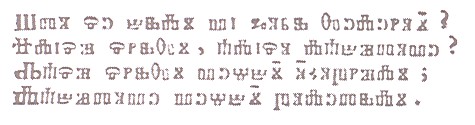

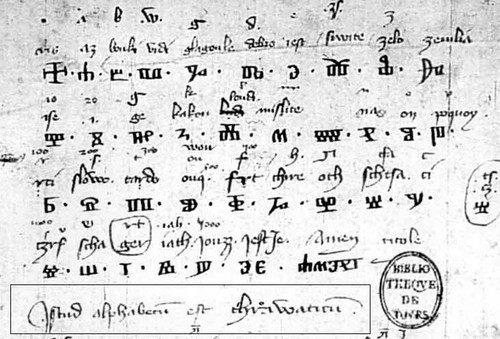

pelling

of Glagolitic Letters, with the

corresponding numerical values, according to George

d'Esclavonie (Juraj iz

Slavonije, ~1355-1416), Glagolitic priest

and university professor on Sorbonne in Paris (his manuscripts are kept

in the Municipal library in Tours, France; in his accompanying text he

wrote: Istud

alphabetum est Chrawaticum

-This is a Croatian Alphabet):

pelling

of Glagolitic Letters, with the

corresponding numerical values, according to George

d'Esclavonie (Juraj iz

Slavonije, ~1355-1416), Glagolitic priest

and university professor on Sorbonne in Paris (his manuscripts are kept

in the Municipal library in Tours, France; in his accompanying text he

wrote: Istud

alphabetum est Chrawaticum

-This is a Croatian Alphabet):

Table of the Croatian Glagolitic Script written by Juraj Slovinac (Jurja iz Slavonije, George d'Esclavonie) handwritten by the end of 1390s in Paris, at the famous University of Sorbonne. Juraj writes Istud alphabetum est chrawaticum (This is Croatian Alphabet!), see boxed below the table. The number above Jus is 5000, not 4000, since 5 at that time was written similarly as we write 4 today (information by the courtesy of Darijo Tikulin, Zadar).

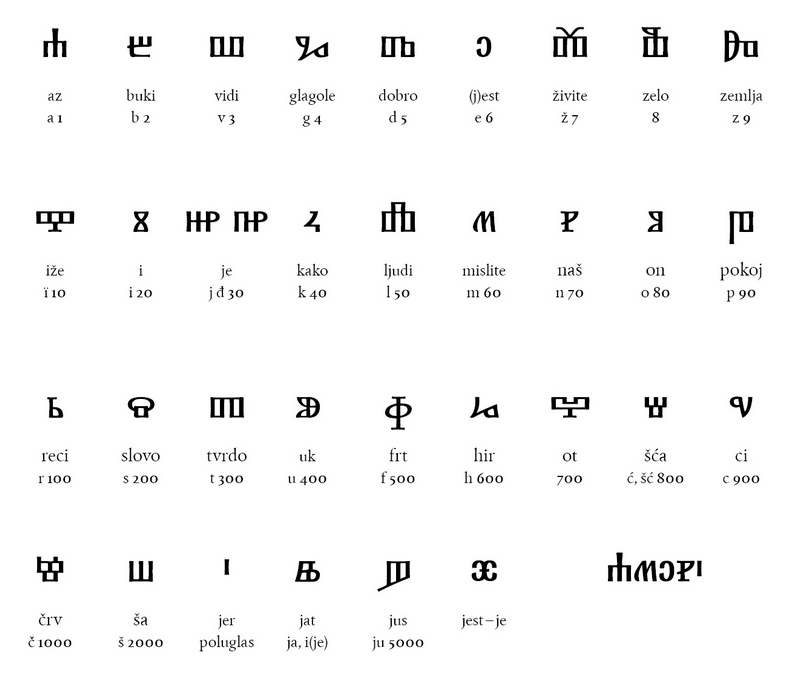

A table of Croatian Glagolitic Script according to Georges

d'Escalvonie

(arround 1400), and with letters created according to the first Croatian printed book

from 1483. The

Croatian Glagolitic font has been created by Filip Cvitić.

|

|

Please, note well that Glagolitic letters appear naturally in groups of nine: first we have nine glagolitic letters representing 1, 2,..., 9 (az - zemla), then 10, 20,..., 90 (izhe - pokoi), then 100, 200,..., 900 (r'ci - ci), and finally thousands, which start with 1000 (ccrv). It is natural to assume, following this scheme, that the prothoglagolitic had nine values for thousands, and not only five (ccrv, sha, jer, jat, jus, jest-je): 1000, 2000,..., 9000. In other words, the prothoglagolitic seems to have had altogether four groups of nine letters:

Information by mr. Dario Tikulin, amateur from Zadar, who has his own reconstruction of three letters in Croatian glagolitic for special sounds, which went out of written practice long ago. Mr. Tikulin also informed me that Simun Kozicic Zadranin (or Benja, Begnius; around 1460-1536) in his Glagolitic book Knjižice od žitja rimskih arhireov i cesarov printed in Rijeka in 1531, used the Glagolitic jus in the meaning of the number 5000 (on p 3, line 5 from below). Here it is

...od slozenija mira *Jus*R*P*Z* (i.e. "...5199

from

the creation of the world")

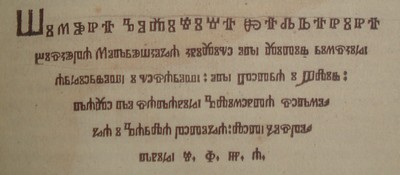

Simun

Kozicic

Zadranin (=

Simun Kozicic

of

Zadar), bishop of Modrus,

Knjizice od zitija rimskih arhiereov i

cesarov (a part of the title

page)

It is interesting that as a rule, Croatian Glagolitic letter zelo (8) is oriented to the left, not to the right. This discovery has been incited by a question of Mr. Milan Pajičić (then a secondary school student) from Vukovar in 2005, during a basic course of the Croatian Glagolitic Script in the Vukvoar Library delivered by D.Ž.

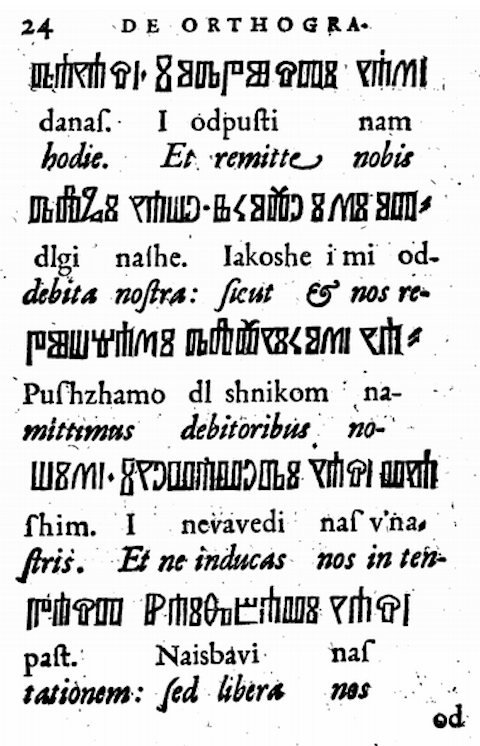

One of preserved manuscripts of George de Sorbonne is kept in the Municipal Library of Tours, France. It contains standard prayers like:

in beutiful Glagolitic handwriting, and with his translation into Latin. He refers to Istria as his Croatian homeland: Istria eadem patria Chrawati. My deepest gratitude go to academician Franjo Sanjek and dr. Dragica Malic for their studies about George (Juraj), and for facsimiles.

You can see a fragmentary, yet impressive list of the most important Glagolitic monuments over the centuries (in Croatian).

Jewels of the Croatian glagolitic culture:

It is generally believed, even by specialists, that the last letter of Croatian Glagolitic is Jus. However, this is not true. There is (at least) one more letter, coming after Jus, which is Jest - je (as spelled by George de Sorbonne). Ten important Croatian Glagolitic abecedariums (they contain 32 - 33 letters) confirm this:

- The Roc abecedarium (Istria, about 1200),

- Pasman abecedarium (Pasman breviary, 14th century),

- two Lovran abecedariums (Lovran is a town on the Istrian peninsula), see [Fucic, pp 238 and 240],

- two Glagolitic abecedariums of Juraj from Slavonia (George d'Esclavonie or George de Sorbonne), kept in France, around 1400,

- Two Glagolitic abecedariums of Bosnian Krstyanin Radosav from 1443, see one of them

- Psalter of Simun Kozicic Benja, printed in 1531 in Rijeka,

- Glagolitic primer from 1527, printed in Venice.

Until 14th century in Croatian glagolitic alphabet Yat was on position 26 (with numerical value 800) and Shcha on position 31. By the end of 14th century they change their positions, so that since then it was Scha that had numerical value 800 instead of Yat. See [Fucic, Glagoljski natpisi p.14], and also [Fucic, Brojevi u glagoljici].

An important personality in the history of Glagolitic script is Dragutin Antun Parcic, a 19th century lexicographer, linguist and Glagolitic priest.

Places to visit in Croatia, possessing Glagolitic monuments:

- permanent Exhibition of the Glagolitic Script (Izlozba glagoljice) in Rijeka, which we strongly recommend to you (prepared by academician Branko Fucic and prof Vanda Ekl; address: Dolac 1, near Korzo in the center, 10-13, 18-20, every day except Sunday and Monday).

- the Alley of Glagolites (Aleja glagoljasa) joining the cities of Roc and Hum in northern Istria (7 km). We recommend that you stop in the village Bernobici near Hum, where there is a Glagolitic lapidarium. Don't miss seeing Roc and Hum - the smallest city in the world!

- permanent Exhibition of the Glagolitic Script in a Franciscan convent of St. Paul on the beautiful island of Galevac (also called Skoljic), near the town of Preko on the (much larger) island of Ugljan (close to Zadar). Contact address: dr. fra Bozo Sucic, Samostan sv. Pavla, 23273 Preko, Croatia. Also an interesting annual International art workshop "Jadertina" is kept on Skoljic.

- Glagolitic lapidarium in Valun on the island of Cres,

- The exotic city of Vrbnik on the island of Krk.

- the Baska tablet (Bascanska ploca, replica) in the church of St. Lucy in Baska on the island Krk.

- Blaca, a remote hermitage built on cliffs on the island of Brac, is indeed a fascinating place. It was founded by Croatian Glagolitic hermits, who fled here from the Turks in the 16th century. The last Glagolitic hermit was Don Niko Milicevic, who was also an astronomer of international reputation, with his published works in such prestigeous journal as "Astornomische Nachrichten" in Vienna, and with rich international correspondence. After his death in 1963 the place was transformed into museum.

- In the village of Gata (which belongs to very old Poljica principality) near Omis, not far from Split, there is a monument to unknown Glagolitic priest, carved by Kruno Bosnjak in 1989.

- Glagolitic path in the village of Gabonjin near Dobrinj on the island of Krk (conceived and realised by Mr Svetko Usalj in 2001).

- and more.

We provide several tables of various types of Glagolitic characters:

- round and angular Glagolitic,

- quick-script and angular Glagolitic (see also Croatian Glagolitic quick-script page),

- some Glagolitic ligatures,

- spelling of Glagolitic letters according to George d'Esclavonie (Juraj iz Slavonije), 14/15th centuries,

- caligraphic letters.

A siginificant property of Croatian Glagolitic Script is that the caracters are not standing above the baseline (like in the Latin Script, Greek or Cyrillic), but rather they hang like a laundry on the rope. This can be clearly seen on the following examples (look at the coordinate net drawn by Glagolitic scribes prior to writing):

The Copenhagen

Missal, Croatian

Glagolitic missal from the 15th century, kept in

the Royal

Library Det Kongelige in

Copenhagen, many thanks to dr. Mladen Ibler, Denmark, for the photo.

The coordinate net is clearly seen, with letters hanging like laundry

on a rope.

Hrvoje

Missal, Croatian Glagolitic

missal from 1404 kept in Turkey in the Library of Turkish sultans,

Topkapi Sarayi in Constantinople. See the coordinate net drawn by

scribe Butko.

It is very probable that some Glagolitic documents are kept in private collections. I would deeply appreciate any such information.

- Glagolitic Breviary of Vitus of Omisalj (1396), written by academician Branko Fucic on the occasion of its 600th anniversary.

- Discovering the Glagolitic Script

of

Croatia, Long Room of the Dublin

University Trinity College

Library, Ireland, from 20th November 2000 till 20th February 2000. The

representative catalogue

with very nice

photos and detailed comments exists. We know of three Glagolitic

documents containing texts of Irish provenance:

- A Croatian Glagolitic miscellany from the first half of 15th century, kept in Oxford (Bodleian Library), contains St. Patrick's Purgatory. The Oxford Miscellany also contains Philbert's Vision which originated probably in Latin in England in the 13th century.

- Tundal's vision (Visio Tugdali), an Irish legend from 12th century, is contained in the Petris Miscellany (Petrisov zbornik) from 1468, the most important Glagolitic collection.

- De Morte Prologus (an imaginary discussion between Man and Death), contained in a Croatian Glagolitic miscellany from 15th century (National and University Library of Ljubljana, Slovenia), and in the Petris Miscellany from 1468.

According to Marin Tadin, Oxford Bodleian Glagolitic Missals (from Canconici collection) have large initials that are of considerable artistic merit.

In 1626 the archbishop of Zadar informed the Congreation de Propaganda Fide that in Dalmatia ther were 113 (hundred and thirteen) catholic parishes in which Glagolitic liturgical books were used. See [Krasic, p. 82].

Glagolitic monuments on the web:

- Relief with the figure of St. Martin, Senj, 1330

- Lintel with Glagolitic inscription, Baska, 1626

- Reliquiary with Glagolitic inscription, Novi, 16th century

Important projects for the future:

- Glagolitic palaeogrpahy (and also Croatian cyrillic);

- Acta

Croatica;

in Surmin's last

1898 edition of Acta Croatica which is rather incomplete, we read a

1288 muniment about Stipan from

old Dubrovnik, the Glagolitic

bishop of Modrus

in Lika, p. 74); see also [Modrus,

p. 112]. The content of the

muniment is here.

As pointed out to me by Mihaela Sokic from Dubrovnik, the Old Dubrovnik (Stari grad Dubrovnik) refers to a Bosnian town north of Sarajevo that had existed also after the fall of Bosnia under the Turks in 1463 (nahija Stari Dubrovnik). This town in Middle Bosnia was founded by merchants from the famous Dubrovnik. See a series of three articles by Perica Mijatovic under the common title "Zla kob starobosanskog grada Dubrovnika," in Stecak, Sarajevo, No 65, No 66, and No 67, 1999, and also Pavao Andjelic [PDF]. - detailed catalogue of the Croatian Glagolitic (nobody knows by how many units the preserved Croatian Glagolitic heritage is represented, not even in thousands: 4000, 5000,...?).

Remarks. Some of the most outstanding Encyclopedias in the world contain errors in the presentation of the Croatian Glagolitic Script. As an illustration, we consider the Encyclopedia Britannica only. There it is stated that our national script has no ligatures. However, there are hundreds of them in handwritten books (and their remains) preserved from the 13th to 16th centuries. Another mistake is that the golden period of the Croatian glagolism falls in the 16th and 17th centuries, which should be corrected to 12-16th centuries. The 16th century represents already the beginning of the fall of this script, which is closely related to the Ottoman occupation of large parts of Croatia, and consequently, the enormous material impoverishment of the Croats. It is also claimed that "The oldest extant secular materials in Glagolitic date from 1309." Such materials have existed only in Croatia, nowhere else. I do not know what secular materials from 1309 Encyclopedia Britannica has in mind. If "secular" means "non liturgical", than the oldest known such material is the muniment of "famous Dragoslav" from January 1, 1100 (yes, eleven hundred) where the towns of Vrbnik and Dobrinj on the island of Krk are mentioned for the first time. It is also claimed that Glagolitic script "is still used, however, in the Slavonic liturgy in some Dalmatian and Montenegrin communities." For Montenegrin communities this is not true. Some of the above mentioned errors have obviously been taken from monographs of a British palaeographer David Diringer, and are still uncritically spread by other scholars. Finally, no mention of the Croatian Cyrillic Script was made in any of the encyclopaediae I consulted so far.

Some of important Crotian glagolitic monuments have been destroyed by Italian irredenta, especially in the period of Italian occupation between 1919 and 1943. In Istria various glagolitic inscriptions were destroyed with sledge and chisel: in Lindar, on the cemetery in Mutovrana, in the parish church of St. Juraj in Plomin, on the Sovinjak belltower, in the Church of St. Antun in Vrh, three glagolitic monuments in Hum (one of them at the very entrance, left of the city gates), and other, see [Zgaljic] p. 39. During the Italian occupation of islands of Losinj and Cres the last Glagolitic priest was Frane Krivicic from Valun. In 1930 the Glagolitic mass was still served in several places on the island of Cres, but in secret. See [Milanovic, pp 88-89].

Aleksandar Belich, a linguist from Belgrade, has been probably the only one who tried to attach the Serbian name to the Croatian Glagolitic ("serbo-croatian" Glagolitic, in 1915 and 1926).

Additional information:

- Acta croatica (listine hrvatske)

- Obshtezhitie, the webpage for the study of cyrillic and Glagolitic manuscripts and early printed books, maintained by the University of Portsmouth (UK),

- facsimiles of Croatian Glagolitic books (handwritten and printed),

- recent references related to the Croatian Glagolitic and Croatian cyrillic (bosancica).

- List of the most important Glagolitic monuments over the centuries (in Croatian).

- Baska tablet

- Croatian Glagolitic Epigraphy, academician Branko Fucic

- Croatian Glagolitic manuscripts abroad

- Glagolitic heritage related to Lika, Krbava and Senj

- Senjske inkunabule i Senjska tiskara

- Glagoljica u Slavoniji (in Croatian)

- Hrvatski drzavni arhiv (Croatian State Archives) - glagoljica

- What Was the Name of the Glagolitic Seminary in Priko? by Benedikta Zelic Bucan

- The Croatian Language in Liturgy, author Anonymous (signed with initial V.)

- The Croatian Glagolitic Heritage, by Marko Japundzic