Two giants of

nonviolence and peacemaking:

Mahatma Gandhi of India and Stjepan Radić of Croatia

Content

- Croatian translation of Romain Rolland’s book

- Josip Vandekar, translator of Romain Rolland’s book into Croatian

- Translations of Romain Rolland’s book into other languages

- International echo of Radić’s 1928 assassination in the Belgrade Parliament

- Parallels between Mahatma Gandhi and Stjepan Radić

- Marko Rašica, Croatian painter

- Acknowledgments

- Literature

- Footnotes

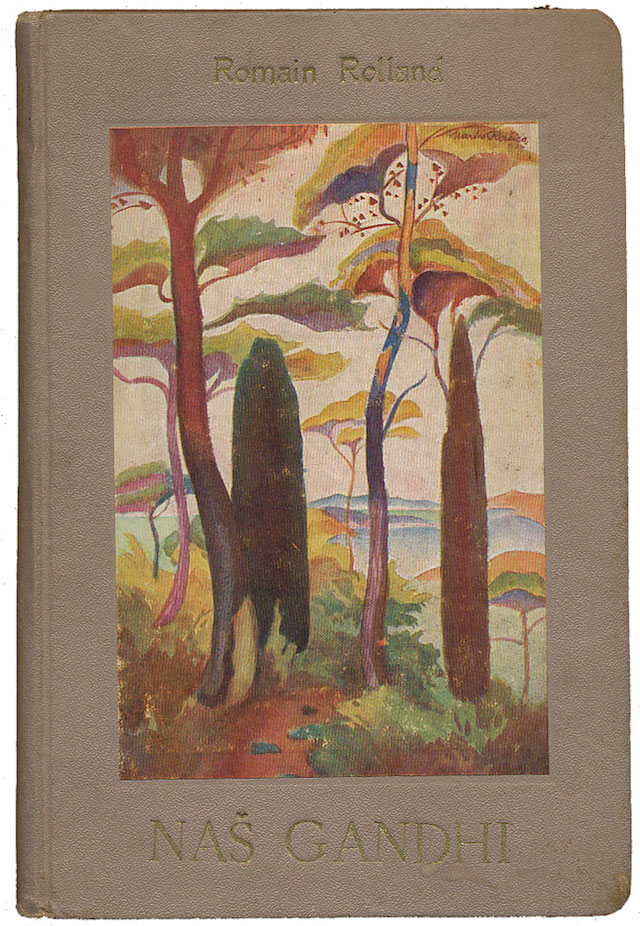

Romain Rolland's monograph Mahatma Gandhi, published in 1924

in Paris,

was translated that same year into Croatian (sic!), upon the initative

of Stjepan Radić (1871-1928),

entitled as Naš Gandhi (Our Gandhi!); on the above photo. The

front cover illustration is by Marko Rašica (1883-1963),

distinguished Croatian painter, born in the city of Dubrovnik.

Croatian translation of Romain Rolland’s book↩

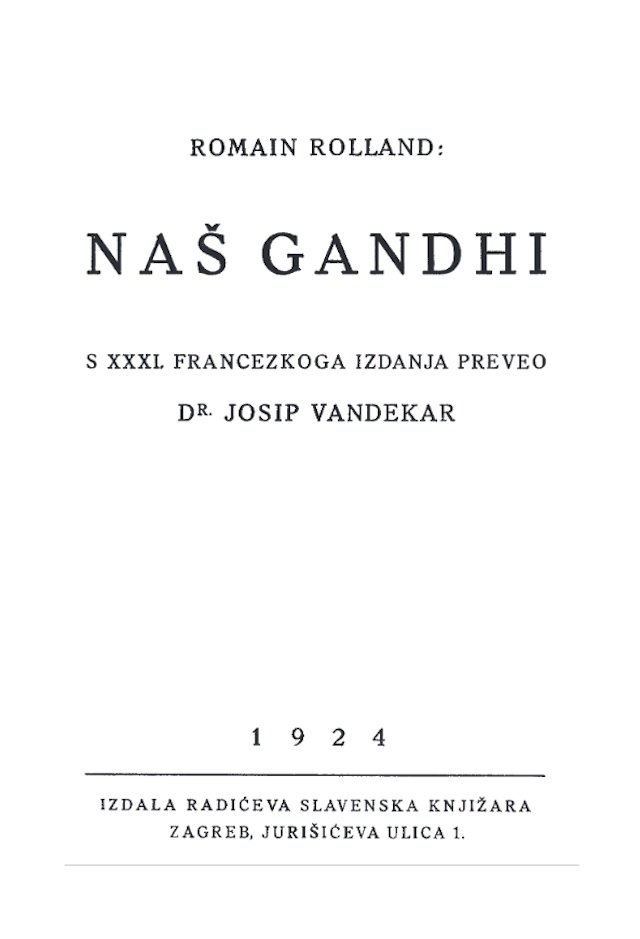

Romain Rolland’s (1866–1944) book Mahatma Gandhi, published in 1924 in Paris, was translated into Croatian that same year. The translation was prepared according to its 31st French edition. The fact that Rolland’s monograph had more than thirty editions in less than one year speaks about the reputation of the author,[*] as well as about the global importance of peacemaking endeavors of Mahatma Gandhi (1869–1948), who at that time was at the age of 55.

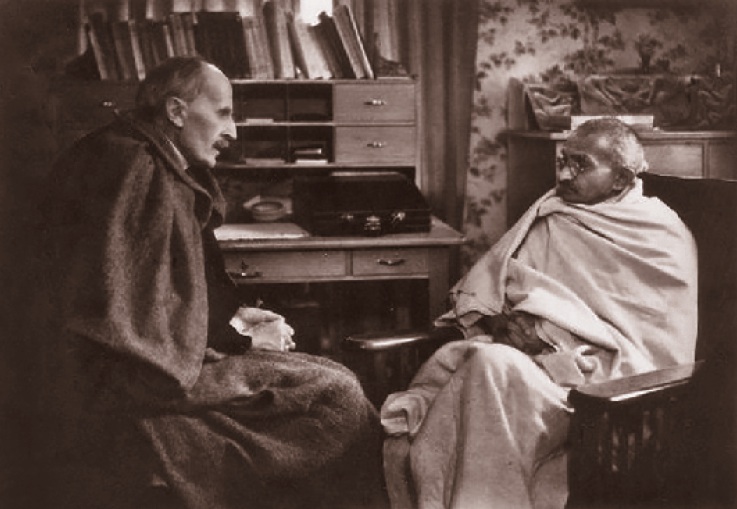

Romain Rolland and Mahatma Gandhi in Paris in 1931.

The Croatian edition bears significant and affectionate title Naš Gandhi (i.e., Our Gandhi), published in Zagreb in 3000 copies. A part of the edition was printed in paperback, a part was bound in a real linen, while a smaller part was lavishly bound in linen and printed on Japanese paper.[*] This shows that the Croatian edition was prepared with a great attention, taking care about material possibilities of buyers.

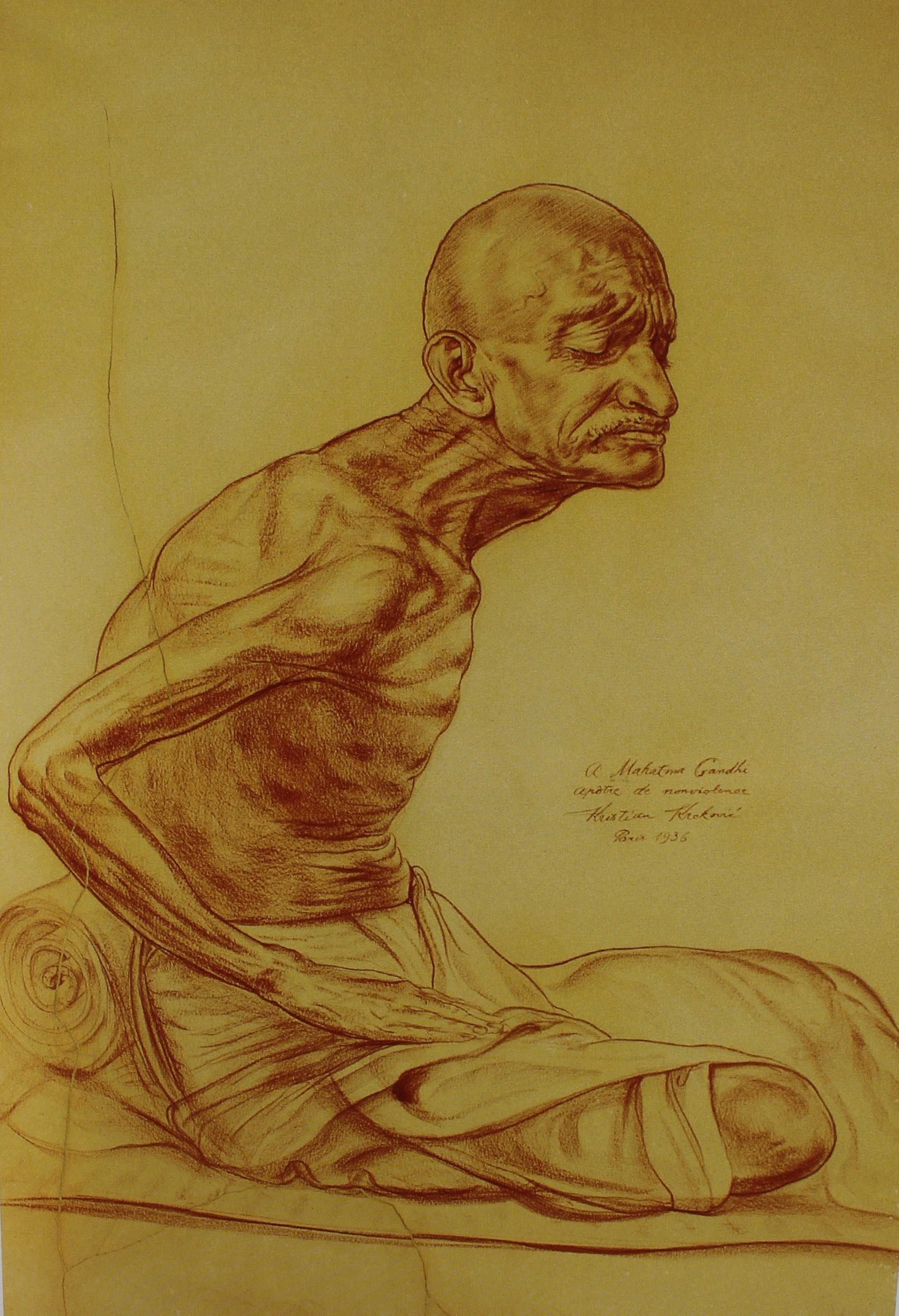

Croatian painter Kristian Kreković (1901–1985) completed this portrait

of Mahatma Gandhi in 1936,

while Gandhi was meditating in his atelier in Paris. They were close

friends.[*]

The impetus for translating Rolland’s book came from Stjepan Radić (1871–1928), who was a founder and president of Croatian Peasant Party.[*] The translation was intended mostly for Croatian peasantry. The publisher of the Croatian translation was Slavic Bookshop (Slavenska knjižara), placed in Jurišićeva street 1 in the very center of the city of Zagreb, which was directed by Stjepan Radić and his wife Marija Radić b. Dvoržakova.[*] The bookshop existed in the period of 1912–1948 in the building of the then Elsa Fluid House, which was a property of a pharmacist Eugen Viktor Feller.[*] For this reason, we assume that Eugen Viktor Feller was among the sponsors of the bookshop. The bookshop of the Radić family was violently cancelled in the circumstances of the Yugoslav communist rule which came to power in 1945.

The inner title page of the 1924 Croatian translation of Rolland’s book,

published under title Naš Gandhi (Our Gandhi).

In the period of 1924–1928, Stjepan Radić published six papers in Croatia’s capital Zagreb dealing with peasantry in India and Mahatma Gandhi.:[*]

- Human nationalism of India (Čovječanski nacionalizam Indije), Dom 17/1924;

- How do greatest peasant peoples struggle? (Kako se bore najveći seljački narodi), Dom 32/1924;

- Croatian peacemaking and Indian nonviolent movement (Hrvatski mirovni i indijski nacionalni pokret), Dom 47/1924;

- Four world peasant giants (Četiri svjetska seljačka velikana), Dom 9/1925;

- Mahatma Gandhi – Peacemaker and savior of India (Pomiritelj i spasitelj Indije Mahatma Gandhi), Narodni Val 134/1927, and

- Rebellion of Asia (Pobuna Azije), Božićnica za 1928. godinu.

Stjepan Radić was born in 1871, two years after Gandhi. He originated from a large peasant family: he was nineth-born child out of eleven. He completed his secondary school education at the Grammar School in Rakovac (now a part of the city of Karlovac), in the same building where Nikola Tesla (1856–1943), distinguished Croatian-American inventor, had his secondary schooling in the period of 1870–1873.[*]

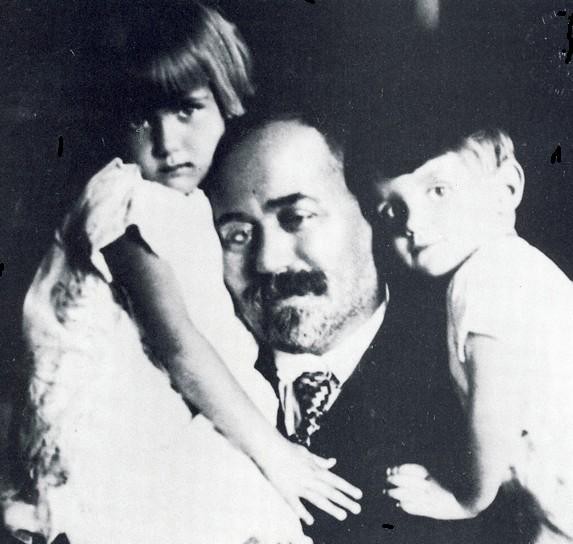

Stjepan Radić in 1925 with his grandchildren Mira Radić and Božidar

Vandekar.

Josip Vandekar, translator of Romain Rolland’s book into Croatian↩

Rolland’s book was translated into Croatian by Dr. Josip Vandekar (1892–30 January 1927), who was Radić’s son-in-law: his wife Milica (1899–1946) was the eldest daughter of Stjepan and Marija Radić. As we can see, Josip Vandekar died relatively young at the age of 35, in Davos (Switzerland) because of tubercolosis.[*] He and his wife Milica had two children: Božidar and Krešo Milutin (or Kreško[*] Milutin).

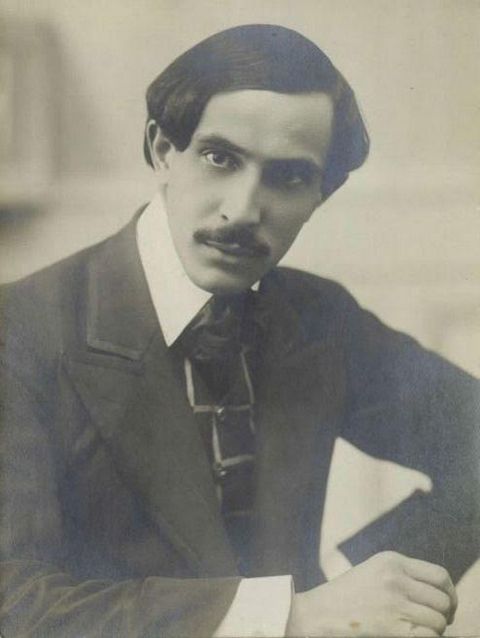

Milica Vandekar b. Radić and Josip Vandekar around 1920.

Photo by the courtesy of Maja Rabaeus b. Vandekar,

grand-daughter of Milica and Josip Vandekar.

Krešo Milutin Vandekar with his daughter Maja in Zagreb in 1958.

Photo by the courtesy of Maja Rabaeus b. Vandekar (on the photo at the

age of around 8),

grand-daughter of Milica and Josip Vandekar.

Grave of Dr. Josip Vandekar at the Mirogoj cemetery in the city of

Zagreb

Dr. Josip Vandekar is not only the translator of Rolland’s book, but he is also the author of the introductory study on pp. IX–XXVII. The book is accompanied with a small dictionary of lesser-known notions, that he prepared on pp. 131–138. We do not know where he earned his PhD and in which field. In the period of 1914–1937 Romain Rolland lived in Switzerland, and then returned to France. During his work on Croatian translation of the book, Dr. Josip Vandekar lived in Switzerland as well (in Davos). Did Vandekar and Rolland know each other, considering an early Croatian translation of the book?

Stjepan Radić delivers a speech in the city of Dubrovnik, Croatia, in 1926.

His last speech in that city was delivered in 1928, in the year of his

tragic death.

Josip Vandekar translated from the Russian a book by Olga Georgievna Bebutova entitled Tsarevich’s Heart (Carevićevo srce), published in Zagreb in 1926.[*]

The second name of Vandekar is rather rare in Croatia – born by 40 individuals only, being most widespread in Hrvatsko Zagorje on the north of Zagreb, in the environs of the town of Pregrada. According to one opinion, this is a guild second name, which bears witness of a mason’s guild (in German, Wand - wall). Another explanation could be that its origin is Flemish, namely from Van de Kar (or Van der Kar), and there are hundreds of thousands of such names. The meaning of Kar in Flemish is cart. We have noticed that the second name of Vandekar exists even in India.

Josip Vandekar was an editor in chief of the Slobodni dom (Free Home), a weekly published by Croatian Peasant Party (with Stjepan Radić as its president). In this journal, it can be seen that at least since 1923 Josip Vandekar was an MP (narodni zastupnik) of the Parliament of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in Belgrade.[*]

In [Božićnica 1931, pp. 107–111] we can find an article of a well-known Croatian scientist Dr. Milan Šufflay[*] (1879–1931), entitled „New viewes to Croatian history“ („Novi pogledi na hrvatsku povijest“). Milan Šufflay was bestially assassinated[*] in the city of Zagreb. A reaction to this political assassination came from Albert Einstein and Heinrich Mann, who wrote a joint protest letter sent the same year 1931 to the League of Nations[*] in Geneva, Switzerland.

Deeply moving testimonies about beatings and assassinations of Croatian peasants have been published by the journal called Evolucija (Evolution), in which Milica Vandekar-Radić served as an editor-in-chief. All this indicates that the Kingdom of Yugoslavia was in fact a country of state terror.[*]

Hrvatski seljački dom (Croatian Peasant House) in Zagreb (today’s

Modern Gallery) in 1925,

adorned with Croatian Coats

of Arms on the occasion of marking 1000th anniversary of Croatian

Kingdom.

The journals Božićnica and Evolucija were adorned with numerous nice vignettes prepared by distinguished Croatian ethnographic painter Zdenka Sertić (1899.–1986.). There we can find an article written by a young Croatian writer Josip Hitrec[*] (then a student of philosophy at the University of Zagreb), who described his half-an-hour encounter with Mahatma Gandhi[*] in 1933 in the city of Pune. His additional very interesting article is [Hitrec, 1934], describing the life of people in India. Since 1944, after more than a decade spent in India,[*] Josip Hitrec lived in the USA as Joseph George Hitrec, where he started his career of professional writer. He published several books describing his life in India.[*]

According to [Lipovac and Radić, pp. 77, 124], Milica Vandekar (b. as Radić in 1899) committed suicide in 1946 during the advent of communist Yugoslavia, immediately after the World War II ended. We can assume that she was in fact assassinated in a Zagreb prison, because she, as a representative of a still very popular Croatian Peasant Party, was considered as a threat for the Communist Party of Yugoslavia.[*] In the same book, Stjepan Radić Jr. (the pianist) described on p. 77 that the whole family of Radić was hiding the truth of her destiny to her mother Marija Radić (b. Dvoržakova, the wife of late Stjepan Radić), by inventing the story that she had „emmigrated“ to the USA. Marija Radić died in 1954, without knowing the fate of her daughter Milica.

Translations of Romain Rolland’s book into other languages↩

The English translation of Rolland’s book was published already in 1924, entitled Mahatma Gandhi: The Man who Became One with the Universal Being, and it was reprinted numerous times throughout the world. The last English edition that we know of was published in 2020.

Rolland’s book had numerous editions in many languages throughout the world. Here are some of them, and those published after 1924 could not be the oldest ones (we have completed our own insights with those stemming from [Fisher, chapter 6. Gandhism, p. 125]):

- 1924, Croatian edition, English (London and New York), German, Flemish, Spanish, Argentinian, and in three languages spoken in India,[*]

- 1925, Portuguese edition, Italian,[*] Polish, Japanese, Chilean,

- 1930. g., Catalan edition,

- 1932. g., Czech edition,

- 1948. g., an edition published in India (in English), ...

Let us remark that Croatian, Flemish, and Argentinian editions are missing in [Fisher, p. 125] for the year 1924, while for 1925 – Italian and Chilean[*] editions are missing. We do not know if there exists a complete and systematic overview of all editions of Rolland’s book about Gandhi published throughout the world.

In [Fischer, chapter 6. Gandhism, pp. 125 and 126] we can find the following claims:

- that Rolland prepared his book about Gandhi collecting and studying the material in 6 to 8 months only, and spending just 3 months for writing it;

- that the first 31 editions Rolland's book were published in just three months during 1924, and that in that year at least hundred thosand copies were printed;

- that in 1926, already fiftieth edition of Rolland's book about Gandhi was printed in Paris.

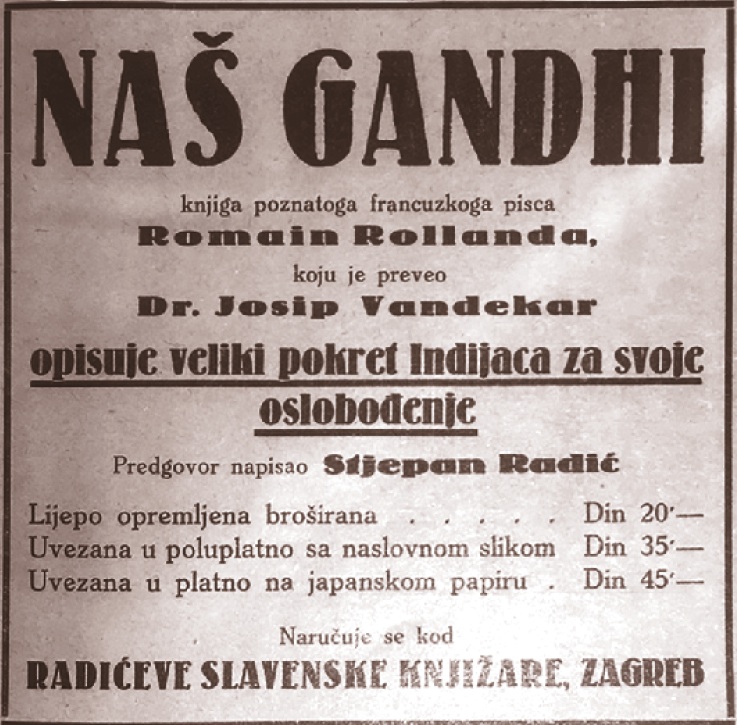

An advertisment for Vandekar’s Croatian translation of Romaina

Rolland's book Mahatma Gandhi

(published as Naš Gandhi, that is, Our Gandhi) that

appeared in Božićnica in 1930 in Zagreb.

International echo of Radić’s 1928 assassination in the Belgrade Parliament↩

Vladimir Radić emmigrated from Zagreb to Paris with his family in 1929, after the assassination of his father Stjepan Radić in the Belgrade Parliament in 1928. In 1931, he defended his thesis written in French, see (V. Radić, 1931), at the School of High International Sciences in Paris. This very interesting thesis, describing in detail the life of Stjepan Radić, and especially the global echo of his assassination, consists of the following five chapters:

Introduction (p. 3)

Chapter 1. (describing Croatia after the First World War; pp. 7-37)

Chapter 2. An official stenogram (taken on the fatal day of 20th June

1928; pp. 38-58)

Chapter 3. Assassination was organized. Two documents... (Assassination

was organized within the Belgrade court, and even announced in advance;

pp. 59-106)

Chapter 4. International press (pp. 107-194)

Chapter 5. (pp. 195-212)

Chapter 4 describes the writing of

- Albanian press (p. 107),

- German press (p. 107),

- South-American Press (p. 124),

- South-American Croatian press (p. 126),

- American press (p. 128),

- Croatian press in North America (p. 132),

- North America (including Canada; p. 132),

- English press (p. 133),

- Antilli islands (p. 143),

- Australia (p. 144),

- Austrian press (p. 145),

- Belgian press (p. 147),

- Bulgarian press (p. 149),

- Estonian press (p. 151),

- French press (p. 153),

- Greek press (p. 166),

- Hungarian press (p. 166),

- Indian press (pp. 169),

- Italian press (p. 170),

- Montenegrin press (p. 173),

- Polish press (p. 175),

- Russian press (in emigration; p. 177),

- Romanian press (p. 182),

- Scandinavian press (p. 184),

- Soviet press (p. 186),

- Swiss press (p. 186),

- Czech press (p. 191),

- Czech Germans (p. 191),

- Slovak press (p. 193),

- Ukrainian press (p. 193-194).

Vladimir Radić (1906-1970) with his wife Milica Radić b. Devčić[*]

and

their son Stjepan Radić Jr (1928-2010), who was later to become

Croatian pianist (professor at the Zagreb Academy of Music) and

politician.

Especially interesting for the needs of this book are the writings of the Hungarian press, and of course, of the Indian press. In the Hungarian press, the daily "Pesti Naplo" of 24th August 1928 describes Stjepan Radić very emotionally, comparing him with Mahatma Gandhi. On p. 168 (lines 5-6), we can read the following: "... Radić, if he had lived in India, would forever have been proclaimed from its nation as Indian Mahatma." In the following paragraph (its line 5), the Hungarian daily claims that: "... in our neighbourhood, we have encountered a legend, a spirituality of Budha and Gandhi." The last sentence of the same paragraph starts as follows: "Stjepan Radić was a son of Budha from the shores of Ganges..."

Indian press (pp. 169-170) is imbued with misrepresentations stemming from the Belgrade official ex-Yugoslav press agency "Avala", insinuating that Stjepan Radić himself was the cause of his tragedy. One can see it in "The Pioneer", the English daily published on 20th July 1928 in Allahabad. On the other hand, "Madras Daily" published on 13th August 1928 in Madras in the Front India, describes in great detail a magnificent funeral of Stjepan Radić, organized in Croatia's capital Zagreb. About 200 thousand people had been marching from 9 am till 6 pm in a funeral procession that ended in complete peace and order. Peasants wore a crown of thorns decorated with Croatian tricolors, on which a fatal bullet which had caused the death of Radić was fastened.

Parallels between Mahatma Gandhi and Stjepan Radić↩

We indicate several interesting parallels between Mahatma Gandhi and Stjepan Radić:

- both Gandhi and Radić were fearless in their peacemaking and nonviolence;

- both Gandhi and Radić where inexhorable in their critique of injustice and violence of any kind;

- both Gandhi and Radić have walked through large portions of their homelands;

- both Gandhi and Radić spent many years in prisons;

- both Gandhi and Radić had a great reliance from the masses, especially from peasantry;

- both Gandhi and Radić had excellent education;

- both Gandhi and Radić were tireless in establishing political awareness of peasantry;

- both Gandhi and Radić were fond of folk songs;

- both Gandhi and Radić died violent deaths: Gandhi in 1948 at the age of 78, and Radić in 1928 at the age of 57 (twenty years before Gandhi).

There are of course numerous differences as well. One of them is their origin: Gandhi was born in a family of a trader, while Radić was of the peasant origin.

Marko Rašica, Croatian painter↩

Marko Rašica (1883-1963), author of the front cover illustration

of the book Naš Gandhi (Our Gandhi, Croatian

edition) by Romain Rolland.

The author of a nice illustration appearing on the front cover of the 1924 book Naš Gandhi (Our Gandhi) by Romain Rolland is Marko Rašica (1883-1963), a Croatian painter born in the city of Dubrovnik. His signature appears on the upper-right part of his drawing[*] decorating the front cover page of Croatian translation of Rollands book entitled Naš Gandhi, i.e., Our Gandhi. He completed his studies at the Academy of Arts in Vienna, specializing in Paris. His artistic credo was "No day without a line". He worked in Zagreb at the School of Crafts (Obrtnička škola). His works of art were successfully exhibited in London, Vienna, Paris, in the Hague, and in Prague. Sanja Žaja Vrbica (Dubrovnik) defended her PhD about Marko Rašica at the University of Zagreb (Faculty of Arts and Letters) in 2011, and published a scholarly monograph about him in 2014.

Stjepan Radić in the Stradun Street in Dubrovnik, in the middle, with Marko Rašica on the

right side in the first row

(with black hair and black moustache), probably in 1927 or 1928. Photo

by the courtesy of

the Ivan Bošković Archive in

the city of Split.[*]

Acknowledgments.↩ We express our gratitude to the National and University Library in Zagreb for helping us in finding the cited articles by Stjepan Radić. Also, many thanks to Mislav Ježić (Fellow of the Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts) for his information that Josip Hitrec travelled to India with Vladimir Filipović.

Note. A suggestion for publishing a reprint of the Croatian 1924 translation of Romain Rolland's monograph about Mahatma Gandhi was provided during the spring of 2021 by the first author of this article (Joginder Singh Nijjar). His idea was occasioned by a public lecture which the second author (Darko Žubrinić) had the honor of delivering on 2nd October 2020, dealing with Mahatma Gandhi and Kristian Kreković as connections between India and Croatia. The reprint was realized by our joint efforts in cooperation with Mislav Ježić.

Literature↩

- Božićnica, seljački prosvjetno politički-sbornik za prostu godinu 1930., edited and arranged by Vladimir Radić [a son of Stjepan Radić], Zagreb 1929.

- Božićnica, seljački prosvjetno politički-sbornik i kalendar za prostu godinu 1931, edited and arranged Milica Vandekar-Radić [the eldest daughter of Stjepan Radić], published by the Radić Slavic Bookshop (Radićeva Slavenska knjižara) in Zagreb

- David James Fisher: Romain Rolland and the Politics of Intellectual Engagement, (in particular Chapter 6. Gandhian), University of California Press, Berkeley – Los Angeles - Oxford, 1988, https://publishing.cdlib.org/ucpressebooks/view?docId=ft538nb2x9&chunk.id=d0e2660&toc.id=&brand=ucpress (visited in July 2021)

- Josip Hitrec: Veče s Mahatmom Gandhijem (A night with Mahatma Gandhi), in: Evolucija, izdavač Milica Vandekar-Radić, rujan-listopad 1933, str. 490 –501. Josip Hitrec: Kako živu narod i maharadže u Indiji (On the life of people and maharajas in India), Evolucija, Travanj-Svibanj, Svezak 4-5, 1934, str. 249-259.

- Zvonimir Kulundžić: Stjepan Radić i njegov republikanski ustav, Azur Journal, Zagreb 1991.

- Marijan Lipovac i Jana Bolant Radić: Dobro ugođena politika – Sjećanja Stjepana Radića mlađeg (Well-Tempered Politics – Memories of Stjepan Radić Jr.), Zagreb 2019.

- Ivan Mužić: Stjepan Radić u Kraljevini Srba, Hrvata i Slovenaca, Nakladni zavod Matice hrvatske, Zagreb 1988.

- Dragutin Pavličević: Progoni i likvidacije Hrvata na području Hrvatske od 1913. do 1941. g. / Persecution and liquidation of Croats on Croatian territory from 1903 to 1941, in: Aleksander Ravlić (ed.), Jugoistočna Europa 1918.–1995. / Southeastern Europe 1918–1995, bilingual Croatian-English edition, Hrvatska matica iseljenika & Hrvatski informativni centar, Zadar 1995, pp. 34 –48.

- Marija Radić: Uspomene

iz života na moga blagopokojnoga supruga Stjepana Radića, (ur.

Maja Maričić i Iva Gruden Zdunić),

(http://marijaradic.pondi.hr/marija_radic_uspomene_web.pdf).

- Stjepan Radić: Hrvatski mirotvorni i indijski nenasilni pokret (Croatian peacemaking and Indian nonviolent movements), Slobodni dom, br. 47, 19. studeni 1924, Zagreb, str. 1-2 (almost identical text to Radić’s Preface to Croatian translation of the book by Romain Rolland)

- Vladimir Radić:[*] Zločin od 20. Lipnja i Medjunarodna Štampa / Obranjeno kao dizertacija na Školi Visokih medjunarodnih nauka mjeseca svibnja 1931. (A Crime of the 20th June [1928] and International Press / Defended as a dissertation at the School of High International Sciences[*] in June 1932, reprinted in Paris, 216 pp.). We believe that the original version was printed in French, probably kept in the indicated School in Paris.

- M. V. [= Milica Vandekar-Radić]: Hrvati kod Mahatme Gandhija (Croatians visiting Mahatma Gandhi), in: Evolucija, izdavač Milica Vandekar-Radić, rujan-listopad 1933, pp. 538–541.

- Darko Žubrinić: Mahatma Gandhi and Kristian Kreković connecting India and Croatia, a lecture delivered on 2nd October 2020 in the Napredak Society in Zagreb, organized by Croatian-Indian Society, in the presence of H. E. Raj Kumar Srivastava, ambassador of the Republic of India to Croatia.

- Stjepan Radić

Footnotes↩

- Romain Rolland was a recipient of the Nobel Prize for literature in 1915.↩

- These data can be found in initial part of the collection [Božićnica 1930.], on its fifth unnumbered page.↩

- The portrait of Mahatma Gandhi is kept in the Kreković Museum (Museu Kreković) in Palma de Mallorca, Spain. As a part of his projects of world peace, in 1926, Kristian Kreković conceived an architectural project of Pantempion (The Temple of the Temples), representing the largest religions of the world, planned to be placed in Mumbay, India. See [Žubrinić].↩

- Until 1925, its name was Croatian Republican Peasant Party (Hrvatska republikanska seljačka stranka, i.e., HRSS), when it was shortened to Croatian Peasant Party (Hrvatska seljačka stranka, i.e., HSS).↩

- Marija Dvoržakova (born in Prague as Marie Dvořáková) was of the Czech origin, a relative of a well-known composer Antonin Dvoržak.↩

- On the fifth unnumbered page near the end of [Božićnica 1931], we can find an advertisement of Eugen Viktor Feller for his product entitled “Happy Hand” (Sretna ruka).↩

- Narodni val (People’s Wave), Dom (Home) and Božićnica (Christmas Gift) were the titles of the journals published by the Radić Slavic Bookshop in Zagreb.↩

- During Nikola Tesla’s schooling in Croatia, this school was a Higher Real School, and not a Grammar School.↩

- Many thanks to Maja Rabaeus b. Vandekar, grand-daughter of Josip Vandekar (and daugher of Krešo Milutin Vandekar), for this information.↩

- The name of Krešo Milutin (Vandekar) appears in at lest two additional ways: Kreško Milutin, or just Krešo (as confirmed by his signature ona postal card sent to Dubrovnik in 1935.). See [Marija Radić], in particular Figures on pp. 14, 19 and 24. According to personal information of his duaghter Mrs. Maja Rabaeus b. Vandekar (to the second author of this article), the name Krešo was most often used, while the name of "Kreško" was jokingly invented and frequently used by his grandfather - Stjepan Radić. ↩

- He was a composer as well, author of a popular tune “Moja mala djevojčica” (My Little Girl), which even today is known in Croatia. The tune was dedicated to Maja Rabeus b. Vandekar, when she was a little girl. Krešo Milutin Vandekar composed two musicals and an opera.↩

- The source of this information is https://www.discogs.com/artist/1060241-Milutin-Vandekar (visited in July 2021).↩

- In 1955, he published a booklet Portretne minijature (Portrait Miniatures) as his own edition on 12 pp, in Zagreb (Prokofjev, Šulek, Strawinski). See https://antikvarijat-bono.com/kategorije/glazba/portretne-minijature/ (visited in July 2021).↩

- Bebutova, Ol'ga Georgievna, Carevićevo srce : (Abastuman) : novel about an heir to the throne: illustrated book / [translated by Josip Vandekar]. - Zagreb : Zaklada Tiskare Narodnih novina, 1926. - 333 pp. : (Entertaining library ; cycle 31, book 378). The title of the Russian original was Сердце царевича.↩

- In Slobodni dom (Free Home) weekly for 1923, one can encounter several of his articles where he was signed as „narodni zastupnik“, that is, as an MP.↩

- Milan Šufflay was a historian of international reputation. He was among the founders of albanology as a scientific discipline, and a polyglot.↩

- Thrashed by an iron rod.↩

- The League of Nations was a predecessor of contemporary United Nations.↩

- More information is available in [Pavličević].↩

- Josip Hitrec (1912–1972) travelled from Croatia to India with Vladimir Filipović (1906–1984), subsequently a professor of philosophy at the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences (Filozofski fakultet) of the University of Zagreb.↩

- See [Hitrec] and [M. V.].↩

- Josip Hitrec lived in India from the summer 1932 till 1944, although he initially planned to stay for three months only. He travelled to India from his native city of Zagreb, using the land route, across Bulgaria, Turkey, Siria, Iraq and Persia.↩

- In 1946, Joseph Hitrec published Ruler's Morning and Other Stories, a collection of tales related to India. For his 1948 book entitled Son of the Moon that won Harper’s Prize, Pearl Buck (Nobel Prize winner, 1938) wrote to be “outstanding novel” by the author who knows and loves India. It was translated into Croatian in 1960 as Mjesečev sin. His book Ruler's Morning, also dealing with India, was translated into Croatian in 1963 as Terorist. More information is available in Croatian Biographical Lexicon (Hrvatski biografski leksikon) and in the article by Željko Ivanjek, “Joža Hitrec: Skitnja mu je bila sudbina” (Wandering was his destiny), published in Jutarnji list, 5th March 2006, Zagreb.↩

- According to information provided to us in 2022 by Dr. Ante Chuvalo (Čuvalo, Croatian historian), the tragic destiny of Milica Vandekar b. Radić was mentioned in Croatian emigrant journal Danica (Morning Star) published in Chicago, 9th January 1963 (Tjednik Danica, Chicago, god. 43., br. 2., 9. siječnja 1963., str. 5.): she was hanged in a prison cell of the Zagreb (communist) police, immediately after the Second World War (“… koju su komunisti objesili u ćeliji zagrebačke policije, odmah iza rata”).↩

- In [Fisher, p. 125], these three languages are called “dialects”. It would be of interest to know the names of these Indian languages.↩

- Published in 1925 in Milan by „Sonzogono“ Co, translated into Italian by Gina Gabrielli. Many thanks to Dr. Ruggero Cattaneo, Milan, for this information.↩

- Of course, Argentinian and Chilean editions were published in Spanish language (more precisely, in Castilian).↩

- Not to be confused with the name of Milica Vandekar-Radić, the eldest daughter of Stjepan Radić.↩

- Many thanks to Jane Sha for noticing this.↩

- Many thanks to Sanja Žaja Vrbica (University of Dubrovnik) for her kind help.↩

- Vladimir Radić (1906-1970), a son of Stjepan Radić (who was mortally wounded in the Belgrade Parliament on 20th June of 1928).↩

- L'École des Hauts Sciences Internationales, founded in 1904 in Paris (and still existing), is intended for those preparing for internatonal and diplomatic career.↩

Emina Kurtagić, Maja Rabaeus b. Vandekar, and Joginder Singh Nijjar,

at the Jelačić Square in Croatia's capital Zagreb, 2024.

Photo by Darko Žubrinić.

Croatia - India

Croatia, its History, Culture and Science