CAPT. A. F. LUCAS

PIONEERING THE

GULF COAST

A

STORY OF THE

LIFE

AND ACCOMPLISHMENTS OF

CAPT. ANTHONY F. LUCAS

By

REID SAYERS McBETH

THE LUCAS GUSHER

Contents

- Chapter I THE MAKING OF AN AMERICAN

- Chapter II SPINDLE TOP

- Chapter III DRILLING THE GREAT GUSHER

- Chapter IV RECOGNITION

- Chapter V MORE ACCOMPLISHMENTS

- Chapter VI PETROLEUM

Chapter I

THE MAKING OF AN AMERICAN

The story of a man who adopted a new land

and saw in it what its own sons had overlooked.

Persistency and a nimble brain, backed by unwavering

confidence in the geological deductions that were the result

of years of study and experience, made Capt. Anthony F.

Lucas the foremost figure in the development of the

mineral resources of the coastal plain territory of Louisi-

ana and Texas. It was he who first attached special geo-

logical significance to the slight elevations on the surface

of the Coastal Plain. And it was he who afterward proved

these to be domes of great economic importance. Upon

these domes is based the development of the vast petro-

leum, rock salt and sulphur deposits in that part of the

L T nited States adjacent to the Gulf of Mexico.

It was Captain Lucas who, flying in the face of prece-

dent and undaunted by unanimously negative advice both

from geologists and oil men, began drilling his first well

for oil near Beaumont, Tex., in 1899. By devising new

drilling tactics he was able to conquer the quicksands that

theretofore had proved an insurmountable obstacle and

learn the secret of the lower rock formations. And his

theory concerning dome deposits of petroleum was spec-

tacularly vindicated in January, 1901, when the well

came in with an output estimated at more than 100,000

barrels of oil a day. The well was the famous Lucas

gusher at Spindle Top, the pioneer of the Gulf Coast oil

development. This location has produced more than

PIONEERING THE GULF COAST

50,000,000 barrels of oil and is still producing. The result

of the Lucas well, which proved the existence of a natural

resource of great worth hitherto unknown and unlooked

for by scientists, was a great influx of capital and the

beginning of an unprecedented era of prosperity for the

district.

And something of the man who brought it about.

Captain Lucas is a great, upstanding man, with the

features of a Roman statesman. He is a man upon whom

one's eyes fall first, even though many others may be in

the range of vision. He stands forth from the throng,

even though he may be in the center of it. He is ideally

American in appearance and spirit, though he was born

in Austria.

Born in 1855 in the city of Spalatro, Dalmatia, Aus-

tria, which was founded by the great Roman Emperor

Diocletian, Anthony F. Lucas (or Luchich, as the name

then was known) was the son of a shipbuilder and ship-

owner on the island of Lesina. His forefathers were of

pure Montenegrin blood. When he was six years old, his

family removed to Trieste, where he passed through the

common branches and high school. It was during this

early schooling that began a series of incidents which

eventually made Anthony Lucas an American. The

Austrian Government even then was endeavoring to

Germanize Trieste, which lies in that stretch of territory

known as "Italia Irredenta." At the end of each scholastic

year Anthony's Italian and Slav classmates met the Ger-

man boys of the school on a hill in the suburbs and settled

accumulated grudges with clubs, stones and fists.

At the age of 18 young Lucas entered the Polytechnic

Institute at Gratz, being graduated two years later as an

[6]

PIONEERING THE GULF COAST

engineer. In 1875, at the age of 20, he entered the Naval

Academy of Fiume and Pola as a midshipman. He was

graduated in 1878 and received a commission as lieuten-

ant. It was his intention to follow a naval career, but,

because of his Slav origin, he soon realized that his oppor-

tunities for advancement were slight. Consequently, when

an uncle who resided in the United States invited Lucas

to visit him, the young naval lieutenant was more than

willing to accept.

Early in 1879, at the age of 24, Mr. Lucas arrived in the

United States. He had obtained six months' leave of

absence in which to make the trip. But he soon noticed

the difference between the two countries, and the pros-

pect of becoming a free American instead of an Austrian

appealed to him strongly. It was at this time that he

began using the name Lucas. His uncle had adopted the

name because of the difficulty Americans had spelling and

pronouncing Luchich. So the young visitor permitted

himself likewise to be addressed as Lucas. When a tempo-

rary position in America was offered him, he went to

work — and has been working in America ever since.

It was in Michigan, where he was visiting, that Mr.

Lucas had his first opportunity to get his hand into the

activities of the country that was about to adopt him.

Saginaw, where he was residing, was the center of the

lumber country. The design of a gang-saw lacked a great

deal of being perfect and the young engineer was asked

if he could solve the problem. He could. And he agreed

readily. The design he completed was satisfactory to the

mill men, and he was asked to supervise the erection of

the saw.

Then, just as the end of his leave was approaching, he

PIONEERING THE GULF COAST

was offered a salary equal to three times his pay as a

lieutenant in the Austrian navy — so he asked to have his

leave extended another six months. But before this sec-

ond six months had expired he had resolved not to return

to Austria. He remained three years with this employer,

meanwhile making application for citizenship. He became

Anthony F. Lucas, American citizen, when he received

his final papers at Norfolk, Va., May 9, 1885. Only once

since his arrival in America has Mr. Lucas visited Austria.

That was in 1887, when he and Mrs. Lucas on their wed-

ding journey visited his birthplace, as well as Trieste,

Fiume and Pola. Although somewhat fearful of an em-

barrassing situation as a result of his informal manner of

leaving the Austrian naval service, Mr. Lucas was not

troubled. On the contrary he was entertained by the

naval officers at Pola. He remained abroad a year.

Returning from Europe in 1888, Captain Lucas took up

his residence in Washington, D.C., and entered the pro-

fession of mechanical and mining engineer. First he pros-

pected for gold with some little success in the San Juan

region of Colorado. He had gained some experience in

gold and copper mining before his marriage, having gone

West in 1883. On this second western trip he remained

two years.

In 1893, when he was 38 years old, Captain Lucas

accepted a position which marked the beginning of his

association with the territory that became the scene of

his greatest successes. He obtained employment as

mining engineer at a salt mine at Petit Anse, La. Here

he remained three years, constantly meeting and master-

ing problems arising from the encroachment of water and

caving in of the underground workings.

[8]

PIONEERING THE GULF COAST

At 41, Captain Lucas began the exploration with dia-

mond drill of Jefferson Island, which was a few miles off

Petit Anse. This island was owned by the late Joseph

Jefferson, the actor, with whom Captain Lucas had be-

come acquainted during his three years of mining at Petit

Anse. The drilling disclosed a great deposit of rock salt

99 per cent pure at a depth of 350 feet. The drill was

stopped — still in salt — at a depth of 2,100 feet.

At 42, beginning to cast his eyes on the economic re-

sources of the coastal plain, Captain Lucas explored on

his own account Belle Isle, La., discovering not only a

deposit of salt, but also of petroleum and sulphur. He

followed this up in 1898 with the uncovering of a great

bed of rock salt at Grand Cote, La. This deposit now is

being largely exploited.

One year later Captain Lucas discovered at Anse la

Butte, near Lafayette, La., both salt and oil. Conditions

for developing the oil production at that time were not

favorable, so he abandoned the discovery and went to

Beaumont, Tex., about 70 miles west of Lafayette. The

Anse la Butte district later became a producing oil terri-

tory and its output of petroleum still is large.

In 1899, at the age of 44, Captain Lucas was attracted

to a slight elevation near Beaumont. It was known locally

as Big Hill, although it arose only about 12 feet above the

surface of the prairie. At the apex were exudations of sul-

phuretted hydrogen gases, which suggested to Captain

Lucas the possibility of an underlying incipient dome

which, in the light of his Belle Isle experience, might

prove a source of sulphur or oil. Then began the series

of events which brought into existence the Gulf Coast oil

fields.

[9]

Chapter II

SPINDLE TOP

Difficulties almost innumerable overcome before

the greatest well ever completed in the United

States was drilled.

What first attracted the attention of Captain Lucas to

the hillock near Beaumont which was to be the scene of

his notable triumph were its contour, which indicated pos-

sibilities for an incipient dome below, and the exudations

of gas at the apex. The sulphuretted hydrogen gas, he

believed, betokened great possibilities to discover either

oil or sulphur. So he decided to drill.

Before starting the test well the explorer leased all the

acreage he could obtain in the vicinity of his proposed

operations. The hill embraced only about 300 acres, of

which he obtained 220 acres. In order to have ample

scope for the development, however, he leased alto-

gether 27,000 acres. This precaution proved unnecessary,

as no oil ever was found beyond the contour of the dome.

The elevation already had been explored by three com-

panies, but none of them had succeeded in sending a drill

deeper than 250 feet. A bed of quicksand had been en-

countered at about 200 feet. But Captain Lucas had

some ideas acquired in his earlier explorations in Louisiana

about coping with the quicksand problem. He knew that

his predecessors had used the ordinary cable drilling

method as used in Pennsylvania, West Virginia, Ohio, etc.,

yet, owing to the generally soft yielding clayey and sandy

formation encountered throughout the Coastal Plain, he

surmised that in order to drill there with reasonable

[11]

PIONEERING THE GULF COAST

expectation of success, a change of method of drilling

should be employed. He had in mind the hydraulic

rotary drilling method, which at that time was almost

unknown for oil-well drilling, with the exception that it

had been used for drilling artesian wells of shallow depths

on ranches and rice plantations.

So Captain Lucas set to work with a crude rotary drill-

ing outfit, and on first penetrating the quicksand, he soon

realized that he had been correct in his surmise of why

the others had failed. He succeeded, however, in passing

the quicksand and bored to a depth of 575 feet. He en-

countered an oil sand — but the well collapsed because of

gas pressure and quicksand.

Then came a series of discouraging incidents that would

have disheartened any but the most courageous. Captain

Lucas decided before proceeding with heavier rotary drill-

ing machinery to seek aid, both geological and financial.

He laid his proposition before several capitalists, but they

failed to enthuse — in fact, some of them openly scoffed at

the idea of oil ever being found in that locality. Anyway,

they opined, if he did find oil it would prove of no com-

mercial value.

One of the men before whom Captain Lucas laid his

project was a former Congressman from Pennslyvania.

A mutual friend brought the meeting about. When he

had heard what Captain Lucas had to offer, the former

legislator proceeded to give a lecture on the dire conse-

quences of unsubstantiated enthusiasm. He asserted fur-

ther that he could not participate in such a wild scheme —

he would lend no financial assistance unless he could count

upon several thousand barrels of production a day. Cap-

tain Lucas got what consolation he could out of replying

[12]

PIONEERING THE GULF COAST

that if he had such a production as the Pennsylvanian

named, it would have been unnecessary for him to seek

financial aid.

Among others to whom he outlined the proposition was

an officer of the Standard Oil Company— H. C. Folger, Jr.

With him to New York, Captain Lucas carried a bottle

of the oil that he had obtained from the well before it

collapsed. The night before the conference with Mr.

Folger was bitterly cold, and Captain Lucas placed the

bottle of oil outside his window to give it a cold test. The

oil, which showed a gravity of 17 degrees Baume, did not

congeal, although the temperature was below zero. De-

lighted with the test, Captain Lucas went to Mr. Folger.

He explained that he did not desire money personally,

but was seeking assistance in further prospecting and

proving the field. Although Mr. Folger's declination was

gracious, he, however, declined. But he did promise to

send Calvin Paine, who then was the Standard Oil Com-

pany's expert, to look into the situation.

Mr. Paine, accompanied by J. S. Cullinan, who later,

as president of the Texas Company, was to take a leading

part in the development of the Gulf Coast field, arrived

at Beaumont a month later. The situation was looking

decidedly brighter, Captain Lucas showed them the loca-

tion of his first shallow well and the heavy oil he had

obtained from it. Then he explained in detail his nascent

dome theory, contending that the elevation was per se a

distinct structure from the surrounding sedimentation of

the prairie, with which the elevation was encircled, and

giving the opinion that it was a dome. The two listened

to all he had to say. Then it was Mr. Paine's turn to talk.

He asserted that there was no indication whatever to

[13]

PIONEERING THE GULF COAST

warrant the expectation of an oil field on the prairies of

Southeast Texas. Furthermore, he stated that he had

visited the oil fields of Russia, Borneo, Sumatra and

Roumania, as well as all the fields of the United States,

and that the indications Captain Lucas had shown him

had no analogy to any oil field he ever had visited. There

was absolutely no chance, he said, of petroleum being

found in such quantity and of such quality as to prove a

paying proposition. Again Captain Lucas showed him the

flask of heavy oil that he had obtained from the well. Mr.

Paine asserted that it was of no value or importance what-

soever, and expressed the further opinion that such heavy

stuff could be found anywhere. Captain Lucas, believing

then and still believing that Mr. Paine was sincere in his

advice that the Gulf Coast enthusiast quit dreaming and

return to his profession of mining engineer, naturally felt a

quavering of faith. It was necessary for him to take

several deep breaths before deciding not to capitulate.

But this was not the only blow the Lucas theory of

dome deposits received. A few months after the visit of

Mr. Paine, two widely known geologists visited the scene

of Captain Lucas' operations. They were Dr. C. W.

Hayes, then chief of the United States Geological Survey,

and E. W. Parker, a former chief statistician of the Geo-

logical Survey. To Dr. Hayes were given in detail by

Captain Lucas his deductions regarding possible accumu-

lations of petroleum about great masses of salt and that

the elevation was a distinct structure from the surround-

ing deposition. But Dr. Hayes did not agree with this

view. He asserted there were no precedents upon which

to base an expectation of finding oil in the great uncon-

solidated sands and clays of the Coastal Plains, and to

[14]

PIONEERING THE GULF COAST

further substantiate his view, Dr. Hayes referred to the

great well drilled by the city of Galveston only 40 miles

off. This well, which was put down to a depth of about

3,070 feet, had cost almost $1,000,000. Dr. Hayes

also pointed out to Captain Lucas that he had no seepages

of oil or other recognized petroleum indications. Captain

Lucas, however, pointed the sulphur dome near Lake

Charles, Louisiana, then under development for sulphur

by Herman Frasch as a possible analogy, and grasping at

a straw, recounted how there the wells were yielding \ Y />

barrels of oil. This was a heavy, viscous oil is true, and

the production was not considered at all as an oil proposi-

tion, but still it might serve to substantiate the Lucas

views in the eyes of the famous geologist; but not the least

encouragement could he obtain from Dr. Hayes.

But, still undaunted, Captain Lucas again set out to

seek co-operation and financial aid. This time he went

to J. M. Guffey, of Pittsburgh, Pa. Mr. Guffey, although

sceptical, finally was induced to give financial assistance,

but, in return, Captain Lucas was obliged to relinquish

the larger part of his interest in the venture. A contract

was entered into by which Mr. Guffey agreed to bear the

expense of drilling three wells, under the direction of

Captain Lucas, to a depth of at least 1,200 feet.

[15]

Chapter III

DRILLING THE GREAT GUSHER

Baffling problems met and solved in completing

well and bringing stream of oil under control.

Those discouraging verdicts of Mr. Paine, Dr. Hayes

and the others had had their effect. They hadn't shaken,

however, Captain Lucas' faith in the economic possibili-

ties of the dome, but they had made him realize that he

could not expect to meet co-operation that had any such

degree of enthusiasm as his own. So, as he expressed it,

in order to obtain financial backing from Mr. Guffey, he

was compelled "to sell

his birthright for a mess

of pottage." But he

wasn't thinking of that

just then. What he was

bent on doing was to

discover what was hid-

den beneath that little

elevation on the plain.

Captain Lucas im-

mediately contracted

with Alfred and James

Hamil, of Corsicana,

Tex., to drill the three

wells specified in the

agreement with Mr.

Guffey. The drilling

mr. alfred hamil. a live wire, here contractors were to re-

IN REPOSE, WHO BROUGHT IN THE LUCAS <* r . My i '

gusher ceive $2 a loot, exclu-

[16]

PIONEERING THE GULF COAST

sive of the cost of casings. For the first well a site was

chosen where the now famous Spindle Top, or Lucas,

gusher was developed. Operations were commenced in

October, 1900. The well was started with 12-inch casing,

the diameter finally being reduced as depth was attained

to 6 inches. The casings were large and heavy, Captain

Lucas remembering the gas collapse that put an end to

his first venture.

Beaumont, however, had not as yet undergone the

change incidental from a pastoral, lumber and rice indus-

try to that of a rich oil field, and in consequence the

various industrial requirements of an oil field were then un-

known and sadly lacking.

An incident may illustrate the arrival of the first carload

of pipe destined to drill the Lucas gusher. This carload,

known as the gondola type, was switched on a siding of

the Southern Pacific branch leading to Port Arthur about

two miles south of Beaumont, and near Spindle Top.

Captain Lucas asked a local concern to proceed and

unload it. The man went to look at the proposition and

reported that such a job was entirely out of his line, and

advised him to get a house-moving concern to do the

unloading. Captain Lucas, therefore, found the house-

moving expert and stated his needs, asking to send a

couple of men to unload the car, as the railroad people

were clamoring for it. The house-mover reported next

morning that he would have to use a derrick and a horse-

power outfit to unload that car, and that next day he

would make an estimate of the probable cost. At that

moment the head drilling contractor, Mr. Alfred Hamil,

arrived in Beaumont and Captain Lucas explained to him

the difficulty he seemed to encounter to get the carload of

[17]

PIONEERING THE GULF COAST

pipe unloaded, whereupon Mr. Hamil suggested to drive

over and look at the formidable proposition.

When they arrived at the switch, Mr. Hamil took off

his coat, climbed up on the car and before Captain Lucas

could stop him had thrown over two lengths of six-inch

pipe to act as skids and began to roll over the heavy

twelve, eight and six inch pipes on the ground so fast

that Captain Lucas was kept busy to roll them out of the

way to make place for the avalanche of pipe rolling down

the skids, so that in less than an hour the whole car was

unloaded.

They got into the buggy and returned to Beaumont,

where they encountered the house-moving contractor, and

this time with a regular estimate for the unloading of the

car. Captain Lucas informed him, however, that he had

no further need as the car had already been unloaded by

the man sitting in the buggy next to him. The contractor

would not believe it, stating that such a thing was impossi-

ble, as he had talked to him in the morning and it was then

afternoon; upon being informed that such was the case,

however, he went straight to the switch to ascertain if

the statement were true.

This incident illustrates how little the local people of

Beaumont were prepared in the art or experience of

handling pipes and machinery; but they soon learned

with vengeance, for it was only a few months later that

not one car, but trainloads of pipes and machinery began

to arrive, and the house-moving contractor, being by that

time convinced that carloads of pipes could be unloaded

without the aid of horse-power winches, ultimately became

a valuable adjunct — not only in unloading pipes, but to

string them along the 1 6-mile right-of-way to Port Arthur,

[18]

PIONEERING THE GULF COAST

where the first oil pipe line was laid in Texas to supply oil

for the refinery going up and for oil export.

The pipe lines in Texas and Louisiana today cover thou-

sands of miles and the capital invested in them aggregates

hundreds of millions of dollars.

The drilling went along with comparative smoothness

until the quicksand was reached. At about 250 feet

trouble began. The drill pipes began to stick; the minute

the counter pressure exerted by the pump was stopped in

order to place another length in, the pressure from below

would manifest itself in a most disconcerting manner.

Sand would fill up into the line for 100 feet or more, thus

making it impossible to proceed. An effort was made to

relieve the 6-inch pipe by going over it with an 8-inch

pipe. But this in turn became stuck. The situation

reached such a stage of acuteness that no progress was

being made. Captain Lucas struggled with the problem,

as did Alfred Hamil. Both worked indefatigably. The

dissolution of the enterprise was imminent. Captain

Lucas, in great distress to proceed with the work, toiled

and pondered and fretted.

But the night after he had arrived at the realization

that the practicable limits had been reached, sleep would

not come to him. His anguish drove his brain to re-

newed effort. Then the solution

came. It was almost morning

when it occurred to him that a

boiler having a 100-pound pres-

sure of water could be pumped

full without any water escap-

ing. Why? Because it was

equipped with a check valve.

[19]

PIONEERING THE GULF COAST

Greatly excited, Captain Lucas dressed himself hur-

riedly and hastened to see Hamil. He explained what he

wanted and, out of boards from a pine box lying in his

back yard, he made a check valve. With perforations in

the center and a small rubber belt underneath, the check

valve was placed between the couplings of the casings.

The device served the purpose admirably. The idea of

having it patented occurred to the inventor. But that —

and the monetary reward that the patent undoubtedly

would have brought — was forgotten in the frenzy of

progress that the check valve made possible.

While the drill works in alternating layers of clays and

quicksand, it is difficult to ascertain to a certainty the

various stratas passed on account that the returns brought

out by the circulating pump are badly mixed, and also to

the possibility to bring up heavy materials. The drill

proceeded, therefore, through various layers of quicksand,

gravel and clays until a depth of about 800 feet was

reached, when a very hard bottom was struck, and here

the 8-inch casing was set. The drilling then proceeded with

a 6-inch fish tail bit, but drilling was found hard, and prog-

ress was necessarily slow. The bit had to be periodically

drawn out and resharpened, while the returns obtained in

the settling pond were puzzling. In one instance, how-

ever, when the bit emerged from the well, a lump of clay

matter adhered to it, and by washing this down it was

found to contain a piece of rock, the size of a small egg,

which on examination proved to be limestone with calcite

intercalations.

This small piece of rock seemed to have given much

comfort to Captain Lucas, for he remarked to the drilling

crew that it looked quite encouraging. The extraction of

[20]

CALCITE AND LIMESTONE

PIONEERIN G THE GULF COAST

this small sample

of limestone and

calcite, together

with some frag-

ments of dolomite

and sulphur, de-

noted, however,

the certainty that

the drill had en-

tered the dome

structure proper,

and proved the

theory that the

well was being drilled in the right place.

The drilling proceeded in this formation for about 300

feet deeper with alternating layers of limestone, calcite,

dolomite and sulphur, the true definition of the material

drilled into, however, was hard to define, owing that the

return as brought out by the circulating pump was prac-

tically slimes. While lowering the 4-inch rod with a re-

sharpened bit the group of men at the mouth of the well

realized that the 4-inch rod, which was attached with the

block and five strands of 2-inch cable, was beginning to

rise. James Hamil, the assistant driller, was on top of the

68-foot derrick, but the beginning of the upward move-

ment of the pipe was so gradual that he had time to reach

the ground before things really began to happen. Captain

Lucas and the drillers stood spellbound as the movement

of the casing increased in momentum. Suddenly, with a

mighty heave, the casing shot into the air, carrying with it

the upper works and heavy tackle of the derrick. At a

height of some 500 feet above the derrick, the heavy rod,

[21]

PIONEERING THE GULF COAST

before a strong wind, twisted, bent and came crashing to

the ground, while the men scurried to safety. The remain-

ing 4-inch pipe, freed of the weight of the upper portion,

followed with even greater rapidity, shot through the top

of the derrick.

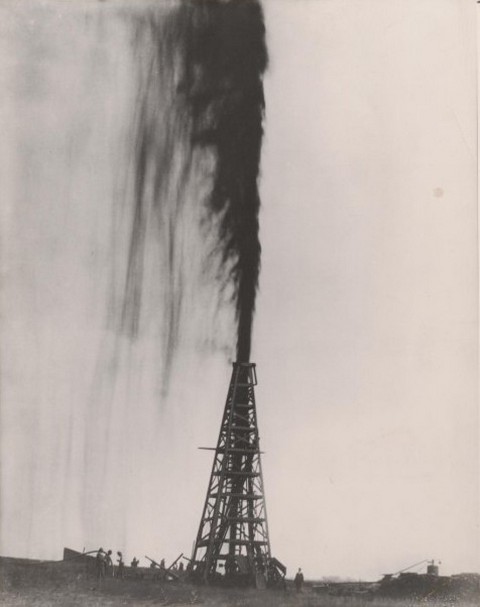

With the second section of casing, there came a gush

of muddy water. This was the water with which the hole

is drilled by the circulating pump when the drilling

is done by the rotary method. The water was followed by

a volley of rocks and fossils, and finally gas. Then came

the oil, which soon settled down to a 6-inch stream spout-

ing to a height of 200 or more feet, and then breaking in

the wind to shower the surface of the hillock. At first the

oil came at the estimated rate of 1,000 barrels an hour;

then it increased to 2,000 and quickly on to 3,000 and

4,000 barrels an hour, where it remained stationary.

On the third day after it had begun to gush, the discharge

then carrying no solid matter and a diminished quantity of

gas, officials of the Standard Oil Company and their engi-

neers estimated the flow to be at least 3,000 barrels an

hour, or about 75,000 barrels in 24 hours. The well is

estimated to have attained a maximum flow of in the

neighborhood of 100,000 barrels a day — the largest by

far of any oil well ever completed in the United States.

It came in January 10, 1901.

Exceeding as it did even the wildest hopes of Captain

Lucas, the well for ten days defied control. His first prob-

lem was to devise a means to control it and of preventing

the absolute waste of the oil in which he was ably sec-

onded by Mr. John Gayly, his partner. In devising a

method of shutting the well in, dams or levees were con-

structed hastily to surround the oil. The first levee, which

[22]

Surfdice_

36' \ Yef/owCfey

2,5.'] Cotirse£reySard

f!4 ' . | Btut C/ay.prefty h<i rd

75' ! /faff grey quick Sctnd

Vsr/ous/y colored grave / from &can to goose egg size.

Coarse grey <y a i ck Sand

$$'] 3/utChy

Z4-' \ Coarse grey Sand witA pyrific eoncre iions.

$5'.\ F//?e <grey Sand vr/M //y-ntfe ,

Qrey S<* -r-cf ' w.'ff! concretions and mac A Iran, ifc

-• Soft Li me Stone

Grey Clay and sulphuretted Ayctrogis# Gas

■-- h'&rcf 'Sands? 'one. w/fA ca/c/te deposits

Grev Sard

Compac i Jr&rcf Sand wit A pyrites '• •;

s= Hard Sandstone 3 nd ce/careous concret/ens

' Zi 1 — Hard Sand

'*?

■//A calcareous concretions

White calcareous SAeffs

Grey Clay

Grey -Sandstone with Oil

Grey day with calcareous concretions

Grs y Clay ge tting Arrets r

--3,-^: ~c-~'~ Calcareous' concretions with c^icHe

Hard grey Clay w itA calcareous concretions*

m ucA fine p yrites.

2.C : Sandstone and pyrites , pretty hard

:.$. .-irrr hard R oc k , apparently Lime stone.

2.4' %. {Ftnc Oil Sand wiiA hard letter towards bo*fom and

' ^J heavy pressure under it, fit/iny casing for 100 feet

j {shove point of dr/i/ing.

I Hard day and Gumbo

Calcareous concretions with layers of hard

Sands ton e & Suiphi

Struck hea vy gas pressure & Bit, which lasted for

snout one hour and then subsided

and nii*.ed With calcareous concretions

nd marine fossils

C&vern ous Dolomite

OlL

Commenced, Oct. 27 r * 1900,

Completed , Jan. 10*? ISO I

PIONEERING THE GULF COAST

was 2 Y /2 feet in height, was overflowed in 24 hours. Suc-

cessive earthen dykes were thrown up until the lake of oil

covered nearly 30 acres. The oil came from the earth at

a temperature of about 120 degrees Fahrenheit. It graded

23 degrees Baume and had a sulphur content of 2 to 4 per

cent.

The clay soil that formed the bed of the improvised

reservoirs held the oil fairly well, but there was a constant

danger of fire. This was accentuated by the throngs of

sightseers that came first from Beaumont, three miles to

the west, and later from more distant points. These,

indeed, were exciting days. Captain Lucas, Alfred Hamil

and their men were working like beavers to save the oil,

and at the same time arranging for the control of the well.

To aggravate the situation the Sabine and East Texas

Railroad Company, whose embankment a quarter of a

mile west of the well formed one side of the lake of oil,

served notice that the oil must be removed because of

danger to the tracks. The marine insurance companies

likewise requested the removal of the oil that had made

its way to Port Arthur and Sabine Pass, seaports sixteen

miles below the well, asserting that the petroleum con-

stituted a menace to shipping and threatening to revoke

the insurances.

A newspaper had published a statement that Captain

Lucas would give $10,000 to anyone who would close the

well. Consequently he was flooded with offers. But he

realized that the solution of the problem rested with him

and his men, so he did not wait for someone to come in and

conquer the well for him. It required ten days to con-

struct out of steel rails a carriage on which to pass an

8-inch gate valve over the 6-inch stream. It was necessary

[24]

PIONEERING

THE

GULF COAST

to have the gate valve and its carriage extremely heavy

in order to withstand the terrific pressure of the oil.

It was at 10 o'clock on the morning of the tenth day

after the well had been brought in that preparations were

made to put the gate valve in place. With the aid of a

block and tackle, horses were used to drag the valve and

its heavy anchorage up to the geyser of oil. As the valve,

which was open, began to cut into the stream, the diverted

force of the oil began to make itself felt on the derrick,

already badly shaken. The derrick began to rock.

Captain Lucas recalls seizing one of the fossils from the

ground and throwing it at the horses to urge them to

greater speed. Had the derrick come tumbling down, it

would have meant starting the work of closing the well

ALFRED HAMIL SEARCHING FOR GAS ESCAPES IN CUBA

[25]

PIONEERING THE GULF COAST

all over again after the wreckage had been removed —

aside from the danger of poisonous gases and injury to

those engaged in the work. But fortunately the derrick

held. Finally the valve was in position, the stream of oil,

again unimpeded, shooting up through it. Then the valve

was screwed tightly to the 8-inch casing. The valve,

securely anchored, was closed without difficulty and the

wildest of wild gushers was tamed.

[26]

METHOD EMPLOYED TO CLOSE THE LUCAS GUSHER

Chapter IV

RECOGNITION

Congratulations from those who discouraged

project — the Spindle Top boom — then solid

prosperity.

Newspaper services heralded throughout the world the

triumph of Captain Lucas. So unexpected was his suc-

cess and so far-reaching promised to be its result, that it

was one of the greatest news sensations in years. The

day after the completion of the well came a telegram from

Mr. Paine extending to Captain Lucas the warmest con-

gratulations and promising to come at once to see the new

wonder. Little did he and Dr. Hayes suspect, however,

that their previous discouraging attitude had contributed

largely toward diminishing the pioneer financial reward.

Their adverse advice had played a part toward putting

Captain Lucas in a state of mind that had made it possible

for the Guffey interests to drive a harder bargain than

otherwise might have been the case.

Mr. Guffey, in financing the undertaking, had organized,

with Andrew Mellon, of Pittsburgh, the J. M. Guffey

Petroleum Company, with a capital of $15,000,000. The

gusher was completed, however, at a cost of less than

$6,000. The capital soon was increased to a much larger

amount, and the title of the company later was changed

to the Gulf Refining Company. The Mellon interests

still are dominant in the great organization.

Among the early arrivals at the well was Mr. Cullinan.

He plunged into the midst of things and became a large

factor in the development of Spindle Top and other fields

[28]

PIONEERING

THE

GULF COAST

that followed it. The Texas Company, of which he was

the first president, was the outgrowth of his efforts.

From the ends of the earth, lured by the prospects of

quick fortunes, came the adventurers, promoters and

speculators along with those who desired to take a legiti-

mate part in the development of the newly discovered

store of wealth. The boom perhaps was the greatest ever

seen in the United States, eclipsing even those of Bir-

mingham and Cripple Creek. Land values, leases and

options leaped skyward. Although the productive area

proved to be only about 300 acres, of which the Guffey

company had obtained through Captain Lucas 220 acres,

the speculative frenzy was not limited by acreage.

Before the advent of the well, common prairie land in

the locality was valued at about $5 an acre. Then up

MEDAL PRESENTED TO CAPTAIN LUCAS BY THE BOARD OF TRADE

ASSOCIATION OF BEAUMONT, TEX.

[29]

PIONEERING THE GULF COAST

it went through the hundreds and into the thousands —

and then into the hundreds of thousands. It is asserted

that one acre within the proven field sold for $100,000.

It is stated that a New York broker stood in the Crosby

House at Beaumont one night after the productive area

had been rather well defined and offered $100,000 cash

for any acre of proven ground in the Spindle Top field —

and was laughed at. So rapidly did prices advance that

options on land, no matter where located, were dealt in

extensively. Women as well as men participated in this

method of speculation. The option was held a few days

and then disposed of, sometimes at great profit.

Companies almost innumerable were organized, with

capitalization aggregating millions upon millions. Other

wells were started as soon after the completing of the

Lucas well as leases and drilling material could be ob-

tained. Most of these were by boom companies hastening

to complete gusher wells in order that they might dispose

of their stock at high prices. The fact that there were no

pipe lines or other facilities for marketing the oil, cut no

figure with them. The gushers were merely for exhibition

and advertising purposes. By the late summer of 1901

more than a dozen wells had been completed, but the

Guffey company was the only one that had made any

serious effort to arrange for the marketing of its output.

This organization was then running a 6-inch pipe line to

Port Arthur, Texas, and had started the construction of

a tank farm at Lucas Station.

One writer asserts that immediately after the completion

of the Lucas well every acre of land within 30 miles of it

was leased. This frenzied speculation continued until a

well off the Spindle Top Dome came in dry. Then prices

[30]

PIONEERING THE GULF COAST

of outside acreage went down with a thump and the boom

was broken.

The 80 acres or so of productive land on the dome that

was not held by the Guffey company was subdivided into

lots of from one to five acres. Quarter acres even sold for

from $50,000 to $100,000. Because of the enormous cash

offers for fractions of acres, and again because no provi-

sion had been made to dispose of the oil that was so

willing to gush from the earth, it appeared to speculators

to be more profitable to sell their small leases than to drill

on them. Tracts as small as 25 by 25 feet changed hands.

Some of the leases only afforded sufficient room for the

erection of a derrick — and it was necessary to obtain

surface rights from a neighboring leaser on which to place

the boiler plant. And each of these tiny leases formed

the only asset of some boom company that was capitalized

for at least $1,000,000.

Captain Lucas recalls an instance in which four com-

panies, each capitalized at $1,000,000, owned jointly a

tract 45 by 45 feet. The companies contributed equally

to a fund for drilling a well in the center of the lot, each

owning a one-fourth interest in the production. The well

was completed and each company was enabled to adver-

tise its stock in full-page displays in the eastern papers,

hinging the advertising upon the ownership of gusher

wells at Spindle Top. Such proceedings continued until

the supply of stock was exhausted or until the collapse of

the boom took the edge off speculative fervor.

When the Spindle Top excitement was at its height,

excursions were run from New York, St. Louis, New

Orleans, Galveston and other cities. These excursions, of

course, were conducted by the speculators and stock

PIONEERING THE GULF COAST

promoters. Trainloads of would-be millionaires arrived

wearing gaudy badges inscribed "All is Well in Beaumont."

And a dozen wells would be set to spouting away for their

entertainment. Wagers even were laid as to which well

was spouting the highest. President McKinley, then on a

visit to the West, was invited to Beaumont and a com-

mittee was organized to arrange to have the greatest possi-

ble number of wells spouting for the occasion — but the

President very wisely declined the invitation.

The city of Beaumont, which successively had been

known as a cattle, lumber and rice-growing center, sud-

denly became famed as an oil metropolis. The city in

succession had had its cattle, lumber and rice kings. It so

happened that shortly after the completion of the Lucas

well, the rice growers of the locality met in Beaumont —

and the rice king, meeting Captain Lucas, protested that

he no longer could lay claim to the crown, so the dis-

coverer of Spindle Top became Beaumont's oil king. Now

that Beaumont has passed the zenith of its glory as an

oil town, it has become, with the deepening of the Neches

River, also a great shipbuilding center.

Hotel facilities at Beaumont were far from adequate

to take care of the throngs that were attracted by the

oil boom. Many persons were unable to find accommoda-

tions either for eating or sleeping. Travel-weary transients

slept on billiard tables, in barber chairs and even in bath

tubs — and paid handsomely for the privilege. But the

crowd was happy. Money was plentiful. And the boom,

as are all booms, was expected to last indefinitely.

All sorts of fantastic schemes were evolved for capital-

izing the situation. A physician gave up his practice in

Washington, D.C., settled in Beaumont and conceived

[33]

PIONEERING THE GULF COAST

the brilliant idea of organizing a salvage company. Capi-

tal $1,000,000 — that seemed to be the favorite amount.

His idea was to gather the oil that the gushers were wast-

ing and hold the oil in storage until it was marketable.

Accordingly he proceeded to organize the company and

market the stock. The company constructed enormous

earthen storage tanks and drained into them through

ditches oil that otherwise might have been wasted. He

succeeded in storing millions of barrels of oil. But a year

later when he was negotiating for the sale of the oil, the

petroleum and tanks were attached by a group of oil-well

owners. The salvage company could not prove owner-

ship — and another million-dollar company was dissolved.

More than one spectacular fire was caused by the

immense quantities of oil held in earthen storage at

Spindle Top, as well as by the crowding of derricks on the

dome. This was one of the worst fears of Captain Lucas

(as well as the railway and steamship insurance com-

panies) from the time the initial gusher began to splatter

the surrounding territory with oil. One of the most serious

conflagrations occurred on March 3, 1901, less than two

months after the discovery. Captain Lucas estimates that

800,000 barrels of oil went up in flames, as well as all the

stores and the houses of the Guffey company workmen

and all the derricks and drilling rigs. The destruc-

tion, great as it was, would have been greater had

it not been that the wind was favorable for fighting the

fire. When it was realized that there was no possibility

of saving the lake of oil, Captain Lucas ordered a counter

conflagration started. When the two walls of flame met

there was a terrific explosion which threw the blazing oil

high into the air and shook the earth. The Lucas well

[34]

PIONEERING THE GULF COAST

was not damaged, it having been covered with a great

sand heap as a precaution against just such an occurrence.

Poems were written and songs were composed setting

forth the glorious results of the oil discovery. One poet,

who also chanced to be a cleaner and dyer, scattered

thousands of handbills that combined poetry with adver-

tising. Here is one of the ebullitions of King, the dyer:

A MILLION BARRELS

When the oil is aspoutin'

And the Beaumont folks is shoutin'

And Lucas has realized his dream,

Just remember, I'm still workin'

And my business I'm not shirkin',

So bring me all your siled clothes to clean.

And if you ventured near the geyser

When you should have been much wiser

And your clothes got full of Lucas grease,

The spots I'll all remove and

Press them slick and smooth

An' in your pants I'll put the proper crease.

And by patronizing me, you

Help the town you see —

And that's been the tried and proper caper,

And in one year from this date

Bradstreet us high will rate

And I will build a 90-story scraper.

So Speculator, Grafter,

And the gang that follows after,

[36]

PIONEERING THE GULF COAST

Your star of luck is looming up on high.

While you are carrying off the money

Please don't forget, ma honey,

The King that does the expert clean and dye.

The town truly was badly in need of cleaning. The air

was impregnated with sulphuretted hydrogen gases, which

turned the white paint on houses, as far away as Beau-

mont, a dirty drab. The silver in homes fortunate enough

to possess such ware turned black, as did the silver coins

that are such a common medium of exchange in that

section of the country. But King's poetical masterpiece

contained a little less of cleaning and a little more of the

spirit that was rampant around the oil field. Here it is:

'CAUSE LUCAS HE STRUCK ILE'

Once I was a farmer man

Who owned a piece of ground

Where 'taters, corn and sich like grew

That I peddled over town.

But now I'm rich and money have

And live in bang-up style,

And it came about without a doubt

'Cause Lucas he struck ile.

I done bought my wife a diamond ring

To wear upon her hand,

My daughter Sal a peane grand — -

She plays to beat the band.

We're going to hire a Pullman car

To travel East in style,

And it comes about without a doubt

'Cause Lucas he struck ile.

[37]

PIONEERING THE GULF COAST

And when we get to big New York

The people they will stare,

And shout "Hurray! There goes the Jay,

The oily millionaire."

We'll show the Gotham folks just how

To put on Beaumont style,

And it comes about without a doubt

'Cause Lucas he struck ile.

We'll hire old Souse and his band

At a thousand plunks a day,

To follow us 'round the streets of York

And rag-time music play.

We'll buy our kids an automobile,

Dress in the latest style,

And it comes about without a doubt

'Cause Lucas he struck ile.

And when to Beaumont we return

With money for to burn,

On future oil prospects we'll have an eye,

And all our sailed clothes we will bring

To that Famous Cleaner King,

The man who does the expert clean and dye.

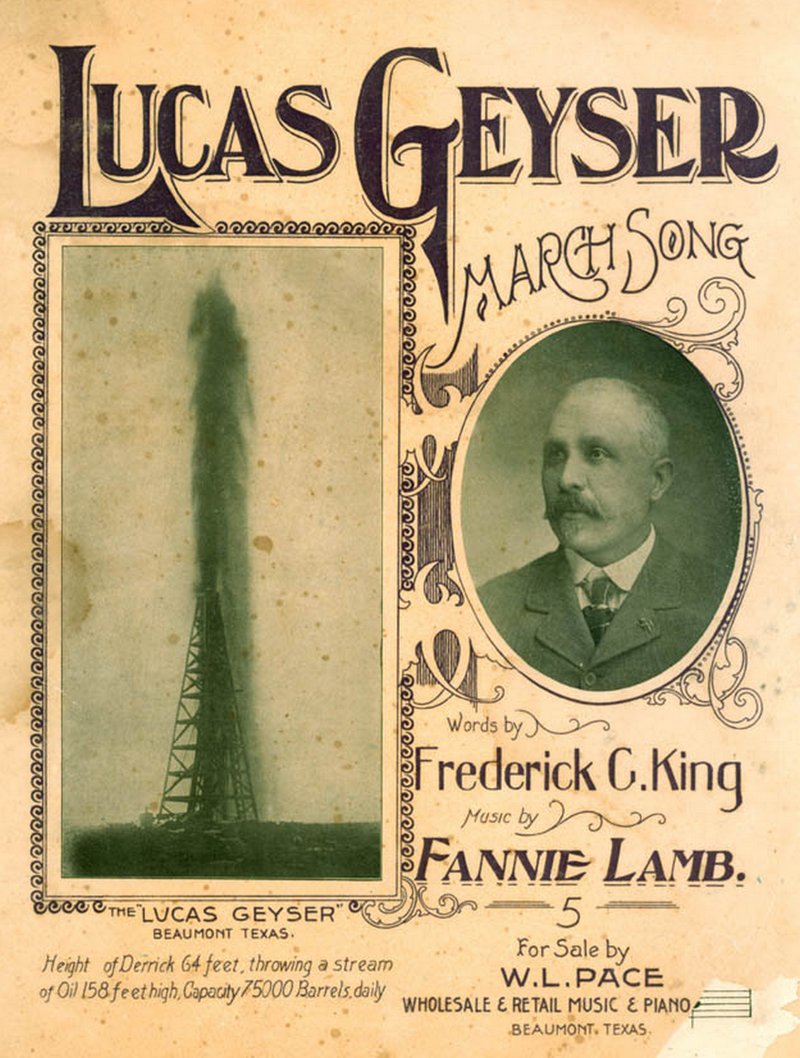

The story of the Lucas accomplishment and the result-

ant frenzied rush even was set to music, and the song,

bearing on the cover pictures of Captain Lucas and his

gusher, were sold at Beaumont music stores. The words

of "The Lucas Gusher March Song" are by Frederick

C. King and the music by Fannie Lamb. The words

follow :

PIONEERING THE GULF COAST

Let me tell you of the greatest town the world has

ever seen,

I know you'll not believe me, it does seem like a

dream,

When I tell you of the geyser that spouted up green

oil,

But it's right down here in Texas, in good old Beau-

mont soil.

Ten thousand barrels of greasy goods came spouting

out the pipe,

The railroads brought a million in to see the wonder

sight.

The oil it spouted up so high you could not see the sun,

It flowed in rivers, lakes and streams, you ought to

see it run.

CHORUS

The streets were filled with happy folks who left their

daily toil.

The news was passed from mouth to mouth that

Lucas had struck oil.

The millionaires came pouring in the wonder for to see,

And the farmer who owned the land, his heart was

full of glee.

They all grabbed Lucas by the hand and shook it

until sore,

They tried to lease the Public Square for more oil for

to bore,

The happy owners of the land, this lucky Beaumont

soil,

Had to carry a gun to keep the gang from boring

them for oil.

[39]

PIONEERING THE GULF COAST

The Standard they came quickly in with millions at

the back,

Old "Golden Rule" of Toledo fame brought his

money in a sack,

The Crosby got so full of folks with four men in a bed,

And before the rush was over they stood them on

their head.

You talk about your Klondike rush and gold in

frozen soil,

But it don't compare with Beaumont rush when

Lucas he struck oil.

So if you want a lease for oil you must be an early riser

To get a whack at our Cracker Jack, The Famous

Beaumont Geyser.

At the height of the boom, when companies were being

organized by the dozen, local newspapers offered pre-

miums for the most catchy names under which these new

companies might sail. To his eternal credit, however, be

it said that Captain Lucas did not lend his name to any of

these stock-jobbing propositions. On one occasion a trio

of promoters called his attention to the fact that there

was no Lucas Oil Company, and asserted that they

desired to perpetuate the name of the originator of the

new industry. They had excellent banking references,

which they exhibited before outlining their proposition.

They suggested that it was their desire to finance a Lucas

Oil Company with capital of $1,000,000. For the use of

his name as president they offered Captain Lucas 10

per cent of the stock.

Naturally, Captain Lucas asked regarding the assets of

the company which they proposed to have bear his name.

[40]

PIONEERING THE GULF COAST

The promoters assured him that they had acreage with

prospects equal to or perhaps even better than Spindle

Top. To this Captain Lucas replied that, if such were

the case, the completion of the arrangements might be

accomplished without difficulty. All that he desired, he

said, was to be taken to the land in order that he might

examine its economic possibilities. They hesitated over

this, suggesting that, as Captain Lucas was such a busy

man, it shouldn't be necessary for him to go through the

formality of looking over the acreage. But Captain Lucas

persisted, asserting that, as it had not been his experience

that anything was obtained without effort, he would feel

that by examining the land and finding it as meritorious

as represented he would have earned his 10 per cent

interest.

Finally a map of the land was produced. Captain Lucas

already was acquainted with the location, so it wasn't

necessary for him to visit it again. He quietly declined

to have any part in the proposition. The promoters

insisted on knowing his reason.

'There is no oil on that land," Captain Lucas finally

retorted, in order to close the interview.

"What is that to you, Captain Lucas, so long as you are

made president and get your 10 per cent of the capital

stock, which would be worth par as soon as it was incorpo-

rated?" This came from the leader of the trio — and he

spoke somewhat heatedly.

It wasn't far to the door, and the spokesman got through

it without any effort on his part. The others, viewing the

forced departure of their companion, left as rapidly and

as unobtrusively as possible. And there never was a

Lucas Oil Company.

[41]

PIONEERING THE GULF COAST

Just before the breaking of the boom an Englishman

sought out Captain Lucas and urged him to accept a

valuable scarf pin, not only as a token of esteem, but also

because he was grateful — Captain Lucas' success, he ex-

plained, had enabled him to clear nearly $200,000 dealing

in options. In presenting the pin the Englishman re-

marked that he knew of the completion of the well almost

24 hours before Captain Lucas himself knew it. He

explained that when the news of the discovery was

flashed over the world, he was at Bombay, India, the

calendar there reading January 9, whereas in the United

States it was January 10. He had taken steamer next

day for Liverpool and from there to New York, arriving

at Beaumont in time to realize handsomely on the dis-

covery.

The collapse of the boom, with the completion of an

unproductive well off the Spindle Top dome, wiped out

the fictitious values that had been put on hundreds of

square miles of territory in that section of Texas. But

then a new and substantial era came. It was based largely

on real assets and there was a seriousness of purpose about

it. The companies that had been organized on something

tangible survived. The others failed. It was a case of

the survival of the fittest. New and responsible com-

panies were organized, new pools were discovered from

time to time, pipe lines were laid, refineries erected and

serious plans made for commercializing the vast stores of

petroleum. In conjunction with the pipe line and re-

finery systems, great numbers of steel storage tanks,

commonly known as tank farms, were erected. Today a

tank farm skirts the edge of the Spindle Top dome. But

Spindle Top long since has passed the glorious days of

[42]

PIONEERING THE GULF COAST

her great productivity, so the tanks today contain oil that

has been transported perhaps from the fields of Okla-

homa and Kansas by the pipe lines that link those fields

with the refineries that the Lucas discovery caused to be

established at various ports along the Gulf Coast. Many

of these companies have their own fleets of tank steamers

that carry oil not only to the ports of the Atlantic and

Pacific, but to foreign countries as well. In fact, the

Standard Oil Company named at that time one of their

new crack steamers the " Captain A. F. Lucas." Millions

upon millions of capital have been invested by these com-

panies.

Here are the names of the oil pools that have been

opened in Louisiana and Texas since Captain Lucas at

Spindle Top demonstrated the correctness of his deduc-

tions regarding petroleum deposits in the domes of the

Gulf Coast: Jennings, La.; Sour Lake, Tex.; Anse la

Butte, La.; Saratoga, La.; Batson Prairie, Tex.; Humble,

Tex.; Vinton, La.; Edgerly, La.; Goose Creek, Tex.;

Hoskins Mound, Tex. ; Welsh, La. ; Matagorda, Tex. ;

Big Hill, Tex.; Markham, Tex.; New Iberia, La.; Bryan

Heights (Freeport), Tex.; Damon Mound, Tex.; Caddo,

La., and Sabine, which lies both in Louisiana and Texas.

But the number of the fields that resulted does not indi-

cate so graphically the far-reaching importance of Cap-

tain Lucas' discovery at Spindle Top as do the oil-produc-

tion figures for the territory. The total production of the

Gulf Coast fields from Spindle Top up to and including

19 1 7, according to estimates of the United States Geo-

logical Survey, has been 360,149,955 barrels. (The figures

used for 19 17 are the preliminary estimate of 26,900,000

barrels.)

[44]

Chapter V

MORE ACCOMPLISHMENTS

Other explorations made by Captain Lucas

in Coastal territory and their results.

Although Captain Lucas retained his financial connec-

tion with the Guffey company only a little more than

six months after the completion of the great Spindle Top

gusher, he did other interesting exploratory work for that

company before the connection was severed. He obtained

land and drilled for the Guffey company on a dome then

known as Bryan Heights, which is about 40 miles south-

west of Galveston. It was here that in July, 1901, at

a depth of 800 feet such a powerful flow of sulphuretted

hydrogen gas was encountered that everyone was driven

off the location.

The Guffey company unfortunately neglected the

Bryan Heights discovery, and the lease became forfeited

in the next three years. Subsequently it was taken up by

speculators, who induced Eric L. Swenson, a New York

banker, to become financially interested on the basis of

positive knowledge of the existence on the property of a

great sulphur deposit. Mr. Swenson organized the Free-

port Sulphur Company, which is exploiting the deposit.

The company is recovering the sulphur by the method

as applied by Herman Frasch at a similar deposit in

Louisiana. The process consists of melting the sulphur

with hot water and then forcing it to the surface by the

pressure of hot air. This company and the Union Sulphur

Company are two of the principal producers of sulphur

in the Lmited States.

[45]

PIONEERING THE GULF COAST

Another well drilled by Captain Lucas for the Guffey

company in 1901 was on a tract of land known as Damon

Mound, in Brazoria County, Tex., some 30 or 40 miles

from Houston. In order to obtain the lease on this dome,

it was necessary for Captain Lucas to promise the owner,

J. H. Herndon, that the well would be called by his name.

Although the well became clogged and ruined at a depth

of 1,600 feet, it hardly could be regarded as a failure,

because it enabled those who were drilling it to ascertain

the existence of a bed of sulphur, oil and rock salt.

This promising field was abandoned until about 191 5,

when Ed. F. Simms, of New York, again began to prospect

the dome, which rises to a height of 96 feet and is one of

the largest structural domes on the Coastal Plain. The

result was that several wells were completed with daily

output of from 5,000 to 10,000 barrels each. On another

part of this dome a sulphur bed is being exploited, and

deeper down an enormous deposit of rock salt extends to

an unknown depth.

It was about midsummer of 1901 that Captain Lucas

severed his connection with the Guffey company. He

realized the financial influence of Mr. Guffey and the

Mellon group as compared to his own, and sold to them

his interest in the company for a satisfactory sum. His

chief reward, however, was to have created a precedent

in geology whereby the Gulf Coast has been made to

yield millions upon millions of barrels of petroleum.

His explorations at Damon Mound netted him nothing

in the way of monetary remuneration. However, he pur-

chased two tracts of land at the time he was drilling, and

two additional tracts amounting to ten acres were pre-

sented to him by the Cave heirs, of Paducah, Ky. As he

[47]

PIONEERING THE GULF COAST

did not deem his operations here satisfactory however, he,

of his own accord, deeded back the tracts presented him

by the Cave heirs. Later they became very valuable, as

they produced large quantities of oil. Captain Lucas re-

tained the tracts he had purchased, amounting to seventy

acres, and saw them develop into substantial assets.

In selling out his holdings to the Guffey company, Cap-

tain Lucas also retained the leases he had acquired at

High Island, near Galveston, 70 miles southwest of

Spindle Top.

After spending considerable time in additional explora-

tory work in this locality, Captain Lucas became con-

nected in 1902 with Sir Wheetman Pearson, now Lord

Cowdray, who has large oil interests in Mexico and is

head of the Mexican Eagle Oil Company, Ltd., and allied

concerns. Captain Lucas first went to Coatzacoalcos, now

known as Puerto, Mexico, where he located two oil fields,

one known as San Cristobal and the other as Ialtipan on

the Tehuantepec Railroad. The San Cristobal field pro-

duces a light paraffine oil of high quality, while the other

field is productive of a somewhat sluggish heavy oil. Both

are regarded as oil fields of great promise. They are in

southern Mexico. The Pearson interests also own large

oil concessions in the Tampico field, the British navy

obtaining a large part of its fuel oil supply from Pearson

leases.

When, after three years as advisory engineer for Sir

Wheetman, Captain Lucas decided to return to Washing-

ton and resume the profession of consulting engineer, the

British capitalist made him a flattering offer to remain as

managing engineer in Mexico. Mr. Lucas, however, de-

clined and in 1905 returned to Washington.

[49]

PIONEERING THE GULF COAST

While in Mexico, Captain Lucas, through the instru-

mentality of his employer, went by way of Oxaca to a

point near Port Angel on the Pacific Coast in the State

of Vera Cruz, where the son of President Diaz and other

capitalists had been operating for oil. There were no safe

ports near the scene of operations, and it was necessary

to beach barges of supplies that were towed from San

Francisco. Many difficulties were being encountered in

the drilling, which was in pure syenite, a crystalline rock

that ordinarily would not be expected to be productive

of oil, although there were some showings of neutral oil

on the surface.

Captain Lucas discouraged the continuation of the

work. Because they already had invested large sums of

money, the operators, however, did not receive the advice

gracefully and continued the work for another year and a

half. They finally were compelled to abandon the proposi-

tion, and the field never has produced oil. While here,

Captain Lucas contracted an illness that kept him con-

fined to his home for almost a year.

It was after his recovery that he decided not to continue

his endeavors in Mexico. In his private practice of con-

sulting engineer, his work took him not only to the vari-

ous oil fields of the L T nited States, but to such foreign

countries as Algeria, North Africa, Russia, Roumania

and Galicia.

\\ 'hen the Lmited States entered the European War in

191 7, Captain Lucas entered actively into the quest for

war minerals, his experiences with the salt and sulphur

deposits in the Coastal Plain territory making his co-

operation of considerable value. Sulphur constitutes one

of the most valuable of war minerals. His only son,

[51]

CAPTAIN LUCAS (CENTER) AND FRIEND ON RIGHT, GERMAN GUARD

ON LEFT, PHOTOGRAPHED BEFORE BEING PERMITTED TO DESCEND

IN THE STASSFURT POTASH SALT MINES, GERMANY

PIONEERING THE GULF COAST

Lieut. Anthony F.

G. Lucas, went to

France injune,i9i/,

with the Sixteenth

Regiment of Infan-

try, with the first

contingents of

L'nited States

troops to be sent to

the front, his bat-

talion marching in

Paris in the 4th of

July celebrations.

In his early days

of salt and sulphur

mining Captain

Lucas had some in-

teresting and valu-

able experiences. In

fact, it was then

that he laid the groundwork and formulated the theo-

ries that resulted in his later spectacular accomplishments

and placed his name firmly in the record of American sci-

entific achievement.

When he took up salt mining at Petit Anse, La., in

1893, he found the salt deposit only 20 feet below the

drift soil, and the shaft 160 feet deep. The mine and mill

were in bad condition because of the fact that water had

found its way into the mine and caused much caving.

Constant care was required to stem the caving, the water

and the ravages of salt on the mill. He opened long drifts in

virgin ground and adopted the overhead method of mining.

LIEUT. ANTHONY F. G. LUCAS, JR.

OO

PIONEERING THE GULF COAST

A gallery 50 or 60 feet wide and 200 to 300 feet long

was started with a 7-foot undercut. After the salt thus

obtained had been hauled out on tram-cars, a second

undercut 18 to 20 feet in height was started. This in turn

having been cleared away, the final mining was started

with the aid of tripod ladders on which light hand-drills

were placed. Batteries of holes were drilled 10 feet into

the roof, six or eight holes resulting in the shooting down

of hundreds of tons of salt. Greater height then was

accomplished by working from the top of the loose salt.

The roof was arched toward pillars about 40 feet square

that were left standing. Suspiciously loose slabs of salt

were pried from the roof before the chambers were re-

garded as finished and the work of removing the 3,000 to

5,000 tons of mined salt begun. By this method it was

not necessary to use any timbering at all. The mining

cost was about 14 cents a ton, and the salt was of unusual

purity, showing 98.5 to 99 per cent sodium chloride and

the remainder gypsum.

The rock salt deposit at Petit Anse was discovered in

1862 by a negro who was digging a well for water. It first

was worked by the Confederate Government and opera-

tions were continued until the Union forces, attacking by

land and sea, destroyed the works. The plant was not

rebuilt until 1879, when Charleston and St. Louis capi-

talists leased the property. Their handling of the proposi-

tion, however, was unfortunate and the property passed

through many vicissitudes before it reached the stage of

successful development. Before Captain Lucas took

charge of the mine, the encroachment of water, because

of the location of the shaft in a sink caused a great deal of

difficulty.

[56]

PIONEERING THE GULF COAST

This deposit, however, had no rival in Louisiana until

1896, when Captain Lucas, drilling at Jefferson Island, a

few miles to the northwest, discovered at 290 feet the

great bed of salt. The diamond drill was sent down to a

depth of 2,100 feet, where operations were halted as a

result of gossip by persons who were not familiar with

the method it was necessary to employ in drilling. The

drill was still in salt at this depth and Captain Lucas

desired to continue operations until he determined the

location or the geological horizon of the floor of the salt

bed. But the gossiping persons spread the rumor that Air.

Jefferson was being deceived regarding the great salt

deposit, because, they said, Captain Lucas was hauling

carloads of salt from Petit Anse to Jefferson Island. He

had been doing that very thing, but the salt from Petit

Anse was used in making brine with which to bore, so

that the bore would not be enlarged excessively. Had

pure water been used, the walls of the bore would have

been dissolved. Mr. Jefferson listened to the gossip and

asked Captain Lucas if he had found enough salt, as

it was his desire to halt operations. Mr. Lucas replied

that he believed he had found salt in sufficient quan-

tity to salt the entire earth, but that he was proceed-

ing nicely and desired to determine the geological

formation upon which the salt was resting. The actor

didn't happen to be interested in geological research,

however, so one of Captain Lucas' early studies was

balked.

One of the most interesting of the Lucas explorations

was at Belle Isle, which is in the waters of the Atcha-

falaya Bay to the southeast of the other deposits. This

island had been the rendezvous of the famous pirate,

[57]

PIONEERING THE GULF COAST

Lafitte, and his buccaneer companions a century ago.

Numerous legends still are heard in that locality of

treasure that these adventurers buried on the island.

In the neighboring bayous are old sunken wrecks popu-

larly believed to be relics of the buccaneer fleet. Many

expeditions have been formed to dig on the island for the

traditional buried treasures, but there is no authentic

record of success. There is, however, a tale of a myste-

rious Monsieur Leblanc, or Lenoir, who suddenly and

unaccountably became wealthy.

It was in 1897 that Captain Lucas contracted with the

owner to explore Belle Isle on his own account. Four

wells were drilled, the result being the discovery not only

of salt, but also of sulphur and petroleum. Nothing of

interest was found in the first well, but the second en-

countered a 56-foot bed of sulphur, below which was dis-

covered the matrix of a salt dome. By further boring an

oil sand was found at a depth of 115 feet, and a strong

flow of petroleum gas at about 800 feet. Having com-

pleted his contract at this stage, Captain Lucas halted

operations and acquired title to one-half of the mineral

resources of the island.

Owing to the lack of sufficient capital, Captain Lucas

was unable to exploit his oil discovery on Belle Isle. The

island later was purchased by the American Salt Com-

pany, and Mr. Lucas received as his share $40,000 in

bonds and $10,000 in cash. It was his observations in the

Belle Isle operations that led him to study the accumula-

tion of oil around salt masses. He had fully expected the

American Salt Company to put him in charge of the

development but the subject was not broached by either

party.

[59]

PIONEERING THE GULF COAST

A New York man was put in charge of the company's

operations, which involved more than $2,000,000. A

large working shaft was started at a point where the salt

deposit showed nearest the surface — 115 feet. The de-

posit, however, had not previously been sounded by bor-

ing to ascertain its conformity and purity. The salt,

which would have found a ready market with meat

packers, was impregnated with oil and gas. The salt

particles that were bailed from the hole and dumped on

the derrick floor would jump around like pop-corn, or

fire crackers, as a result of the liquefaction causing the

liberation of gas brought in contact with the air. Accord-

ing to Captain Lucas, this is the only salt deposit en-

countered in all his explorations of the domes on the Gulf

Coast showing an oil and gas impregnation through more

than 3,000 feet. It was caused, he believes, by an enor-

mous gas and oil pressure from below the salt deposit.

The salt company

sent its shaft to a

depth of 250 feet

and started driving

toward the interior

of the deposit,

searching for purer

salt. When Cap-

tain Lucas learned

whatwasbeingdone,

he telegraphed to

ask if the drift was

in the right direc-

tion and if Sound-

ly ^^ U~A U J SALT CRYSTALS AT 1500 FEET DEPTH CONTAIN-

ings had been made ING GAS AND j L , belle isle, la.

[61]

Lake Pcingreur

Tide Water Line

JEFFERSON ISLAND.

Tide Water Liue

PETITE ANSE ISLAND.

iHH 1 " BELLE ISLE.

BELLE ISLE.

Sectional Views of Louisiana Rock Salt Deposits.

Scale 1 Inch =800 feet

Clay t$M^ Sand I I Oil bearing Shalo

Oravel IHTiTFTTTI Rock Salt WM Limestone and Sulphur

SECTIONS OF THE SALT ISLANDS, LA.

THE SALT ISLANDS, LA.

GULF OF MEXICO

SECTION ALONG LINE A— B

-Anhydrite arid gas

SECTION OF SALT AND SULPHUR DEPOSITS AT BELLE ISLE, LA.

PIONEERING THE GULF COAST

SOOO FEET

'Contour lines on salt show o'/stance In feet tefow sea level

TOPOGRAPHICAL PLAN OF BELLE ISLE, LA.

with a diamond drill in that direction. The next he

learned was that the salt had been passed through and

quicksand encountered. The mire of the marshes driving

the operators out, barely giving them time to save the

men. Thus the first shaft was lost. It afterward was

found that the salt in this locality formed a depression,

500 feet westward, although it was connected with the

main dome.

[64]

PIONEERING THE GULF COAST

GAS BURNING, TAKEN AT NIGHT IN BELLE ISLE, LA.

Another shaft was started to the westward. The salt

here was reached at a depth of 276 feet. On the top of

this salt was found a layer of about 30 feet of quicksand

which could not be passed through. An expert shaft

sinker was called upon, and he employed a freezing pro-

cess. But he did not put his brine pipes in the salt. He

stopped in the quicksand, so that when the mass was

frozen preparatory to mining, they were just as badly off

as before and could not pass the quicksand. A large sum

of money was spent before this effort finally was aban-

doned. The company then started to explore for oil, but

PIONEERING THE GULF COAST

was not successful. The property finally was disposed of

at public sale and the island now is the property of the

New Orleans Mining Corporation.

In the meantime, Captain Lucas had discovered an

excellent bed of salt at Weeks Island. This is being

worked with commercial success. His discovery of oil and

salt at Anse la Butte provided him with further material

upon which to base his deductions regarding Spindle Top

and other similar structures.

[6?]

Chapter VI

PETROLEUM

History — theories of origin — the hydraulic rotary

drilling system — fuel oil — some of Lucas' deductions.

Petroleum is a term that in its widest sense embraces

the whole of the hydrocarbon family — gaseous, liquid and

solid — occurring in nature. The word itself is derived

from the Latin words petra, meaning rock, and oleum,

meaning oil — rock oil. Although the commercial develop-

ment of the world's petroleum resources extends over

only a little more than a half century, it was gathered for

various ritual uses in remote ages, and later for medicinal

purposes.

Herodotus described in his writings oil pits near ancient

Babylon and the pitch springs near Zante. Strabo,

Dioscorides and Pliny made mention of oil obtained at

Agrigentum in Sicily and used for illuminating purposes.

Plutarch's writings refer to petroleum found near Eba-

tana. The ancient records of China and Japan contain

numerous allusions to the use of natural gas, while petro-

leum, or "burning water," was known in Japan in the

seventh century. The gas springs of North Italy led to